Thursday, March 26, 2020

Survive the Pandemic by Turning Japanese

Here are some of things that may have helped the Japanese to have suffered fewer deaths in the coronavirus pandemic so far include perhaps (I am not connected with medicine):

Here are some of things that may have helped the Japanese to have suffered fewer deaths in the coronavirus pandemic so far include perhaps (I am not connected with medicine): 1. wearing face masks which have been de rigueur for those who are suffering from respiratory illnesses perhaps since the influenza pandemic of 100 years ago,

2. a greater attention to covering ones mouth when one coughs (Japanese ladies cover their mouths even when they laugh),

3. far less dancing and discos,

4. bathing in the evening when arriving home dirty rather than the next morning (having passed the evening and night dirty at home!),

6. drying oneself using single use towels rather than bath towels that may not be washed for a week,

7. high interpersonal distance,

8. boiled sweets (candy) provided at customer service locations partly to reduce customer coughing,

9. generally lots of cleaning and sweeping by everyone from school children to monks,

10. food wrapping or the lack of unwrapped food sales, polythene bagging of unwrapped foods such as fruit at the checkout,

11. non-food product wrapping so that even if the packaging has been handled purchased products are sterile when unwrapped at home,

12. changing of clothing upon returning to the home and arriving at school (school uniforms are worn only on the way there. Pupils often change to track suits in class),

13. removal of shoes indoors,

14. use of a separate pair of slippers inside toilets,

15. passing things to other people with both hands thus interpersonal maintaining distance,

15. the use of semi disposable gunte cotton gloves by service personnel such as ticket inspectors, taxi drivers and anyone doing a dirty task even at home*,

11. the Japanese housewives' love of aprons which keep their clothes clean,

12. the way that Japanese taxi drivers open taxi doors for passengers so they don't need to touch the door handle**,

13. the predominance of uniforms in any job that may involve even a little dirt such as on any sort of manufacturing industry,

14. preference for the "one room mansion" over shared houses and flats,

15. more vending machines allowing purchases without human interaction,

16. the practice of sterilizing ones mattress (futon) by hanging it out in the sun,

17. taking rubbish home rather than littering or even using (non-existent) public waste bins,

18. plastic fairings along the sides of car windows to allow windows to be open a little refreshing car interior air even when it is pouring with rain,

19. a general preference for fresh air over closed air-conditioned rooms.

20. a preference for new things rather than second hand,

21. a greater belief that "cleanliness is next to godliness" and conversely that sin is a sort of defilement,

22,regarding cleaning is a sort of spiritual practice (that at least teaches the importance of cleanliness),

23. respect paid to homes, temples, martial arts gyms and other spaces with cleaning and bowing and greetings at the entrance to such spaces, emphasising the importance of keeping them in all ways good and pure,

24. traditionally according to Shinto scripture considering (skin) disease to be one of the deadly sins,

25. the integration of hand and mouth washing (chouzu, temizu) into Shinto prayer ritual,

26. shame-culture severity towards mistakes and not things that one does intentionally (infection is generally unintentional caused by a lack of vigilance such as in failing to cover ones mouth when one coughs),

27. the traditional provision of hot hand washing wet towels (oshibori) and disposable chopsticks at restaurants (that remain open even now),

28. individual bowls and chopsticks rather than sharing a common stock of cutlery even within the home,

29. sitting next to partners and friends rather than facing them and enjoying their company side by side (e.g. using counter seats),

30 enjoying the presence of others without feeling the need to keep talking all the time,

31. swallowing ones nasal mucus rather than blowing ones nose,

32. the consumption of many healthy foods. An urban myth has it that natto (rotten soya beans) is preventative but the notion that it may help has been rejected by Japanese specialists. Something about the Japanese diet (which is higher in rice, soy, and) may help. Natto contains a serine protease (nattokinease) which may encourage the production of serine protease inhibitors (serpins) which may block infection, or do the opposite. I am not a doctor.

33. Washlet (and other brand) bidets fitted to toilets keeping coronavirus from wiping hands,

34. the avoidance of touchy feely greetings such as handshakes, hugging and kissing,

35. less petting at least in public and less sex out of courtship and procreation, and a greater use of prophylactic sheaths,

36. a greater use of the seated position by males when urinating (sometimes by order in public toilets) thus avoiding urine on the floor and seat and hand to genital contact (male genitals may act as a fomites and while it is not a Japanese tradition, I have taken to washing my hands before and after using the toilet),

37. washing ones hands inside toilet cubicles using a raised flush-cistern faucet/spigot or tiny sinks before touching the toilet door handle,

38. the provision of disposable paper toilet seat covers and or disinfectant for cleaning toilet seats in public toilets,

39. spitting is unacceptable,

40. flatulence is beyond the pale,

41. drinking green tea and various medicinal teas,

42. perhaps the practice of getting neck deep in clean hot baths (Japanese wash before soaking) almost every night,

43. the use of hot spas as a folk treatment for almost everything.

The last two would be my Japan-influenced suggestions for attempting to treat the virus even in the face of WHO "myth busting", but I am not connected with medicine in any way.

I thought that the Japanese would be especially inclined to catch the coronavirus due to their genetics but Japanese culture proved me wrong.

I hope and pray that everyone worldwide stays safe. When Japanese schools reopen in April, the Japanese may face a resurgence of the coronavirus, so, I am praying for Japan too. Perhaps prayer should be added to the list of hygienic behaviours. Many Japanese people pray in the face of adversity (kamidanomi) even if they do not believe in the existence of that which they are praying to. This I think promotes awareness of the strength of ones yearning, and lack of ones power, thereby promoting a kind of humble diligence, hopefully.

The above inaccurate image was drawn freehand by me based on an accurate graph in the New York times.

*One hygiene product that I felt to be lacking Japan is the (Great British!) nail-brush. Upon reflection, however, I have come to realise that there are few nail brushes in Japan because Japanese would always wear gloves before performing a task that is so dirty as to result in dirt getting behind their nails. Oops.

**I now think back with regret at the number of times I have opened Japanese taxi doors for myself, in an expression of autonomy, as if to say I don't need you to open the door for me, and thereby putting my nasty germ ridden hands on the taxi probably forcing the taxi driver to get out and disinfect the door.

Labels: japan, sex, taboo, tourism, ホスピタリティ, 日本文化

Monday, August 22, 2016

Augmented Irreality: World of Light

Japanese children paint cars, trucks, aircraft, including UFOs that then scanned into, and bounce or fly along in, a giant musical city scape traffic jam mural, with which the children can interact. The vehicles are ticklish to the tap. The Japanese children, including my own, go wild because they too are one with the fish: images come to life. Esse est percepi. Video ergo sum.

Before going home the children can have their pictures scanned into onto 3D paper model that they can fold into toy. Their pictures become alive and dwell amongst us.

My video explanation is here

and the production company's explanation is here.

Labels: interdependent, nihonbunka, self, shining, specular, tourism, visualization, 日本文化

Friday, August 12, 2016

The Authenticopiable and the Unique

Many Japanese castles, such as those in Oosaka and Nagoya are, like the "foreign villages" (gaikokumura) scattered around Japan, scale models, replicas or fakes, made out of concrete, not the real ting at all, to the Western whispering mind. To the Japanese if they look the same they are the same. The Japanese are going to collect the unique words as stamps. This guide book to the 100 famouse ("named-") castles of Japan contains an "official" stamp collection book. An example of a stamp is shown in red bottom right. To us the situation is reversed: words are the same whereever they are said, but views are unique so we go to see them. How can the world be so inverted?

Each construal depends simply upon whether from out of that cave or 'crypt' of the mind (Abrahama & Torok, 2005), one is looking or listening with 'mother.' For the Japanese the collectable names are on the outside of the head. There is no Other (Lacan, Mori, 1999, p.163) to authenticate them.

Abraham, N., & Torok, M. (2005). The wolf man's magic word: A cryptonymy (Vol. 37). U of Minnesota Press.

Mori, A. 森有正. (1999). 森有正エッセー集成〈5〉. 筑摩書房. See here with quote.

Labels: cultural psychology, japanese culture, nihonbunka, tourism, 日本文化, 観光

Friday, March 11, 2016

Climbing Authenticopies

Edo period Japanese were fond of visiting Ise Shrine, other shrines and temples, and also famous mountains, none more so than Mount Fuji. However the purpose of visiting Mount Fuji was not to enjoy the view from the top, which as the saying goes is preferred only by stupid bigheads and smoke (baka ya kemuri ha takai tokoro ga suki). So instead of climbing the mountain, they more often chose to climb a model of the mountain, wearing full pilgrim's attire, at one of the shrines at the base of Mount Fuji (Ohwada, 2009, p. 40: quote in Japanese below).

There is no size information in the visual. A bonsai tree looks the same as a massive oak, and a model of Mount Fuji can look the same as the real thing. If you wear the right kit and walk up a model, then you might as well have walked up the actual mountain, because they will look the same way. In he land of the sun-goddess the authenti-copies or simulacra (Baudrillard, 1995) are not words, which Westerners feel to be perfectly copyable because we have a listening comforter, but visual replications such as of mountains in front of Shinto shrines.

Japanese culture is rife with authenticopies such as bonsai, model food in place of menus, dolls, horse and cow sculptures at shrines, masks, pictures of the deceased and his royal highness the emperor, and the god-head (goshintai) of the deities themselves that can be copied or split 'as one can split a fire' (Norinaga, see Herbert, 2010, p.99). The practice of visiting copies continues to this day in the form of creating foreign villages ("gaikoku mura") which fascinate foreign anthropologists and tourism theorists (Graburn, Ertl, & Tierney, 2010; J. Hendry, 2000; Joy Hendry, 2012; Nenzi, 2008). I don't think that they have noticed that the Japanese world is inside out yet, however.

If it were indeed the case, as argued here, that the Japanese world is that of light, an amalgam of images, seen and 'insured' by the watchful eye of the Sun goddess, then in order for someone to pass from Western to Japanese culture, from a Western to Japanese world, they would need to pass through the veil of perception. Perhaps all one really needs to do is find the dead girl that you are talking off to.

Perhaps that is what David Lynch (1992) meant by "Walk fire with me".

The above image is composed of a detail from the model mountains (though not of Mount Fuji) or standing sand (tatesuna) in Kamowake-Kazushi Shrine precinct by 663highland, and image of a monk in a straw hat from gatag copyright free image source.

富士山の場合は、富士山に実際に登山していわゆる富士山禅定(ぜんじょう・登る=修行)を行う者はむしろ砂苦、大多数はしないの富士山神社や諸社寺境内に設けられた箱庭式で模擬登山を行うのであった(大和田, 2009, p. 40)

Bibliography

Baudrillard, J. (1995). Simulcra and Simulation. (S. F. Glaser, Trans.). Univ of Michigan Pr.

Graburn, N., Ertl, J., & Tierney, R. K. (2010). Multiculturalism in the New Japan: Crossing the Boundaries Within. Berghahn Books.

Hendry, J. (2000). Foreign Country Theme Parks: A New Theme or an Old Japanese Pattern? Social Science Japan Journal, 3(2), 207–220. http://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/3.2.207

Hendry, J. (2012). Understanding Japanese Society (4th ed.). Routledge.

Herbert, J. (2010). Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. Taylor & Francis.

Lynch, D. (1992). Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

Nenzi, L. N. D. (2008). Excursions in identity: travel and the intersection of place, gender, and status in Edo Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

大和田守. (2009). こんなに面白い江戸の旅. (歴史の謎を探る会, Ed.). 東京: 河出書房新社.

Labels: authenticopy, japanese culture, Nacalian, nihobunka, Shinto, tourism, 日本文化

Friday, January 29, 2016

Naruto Whitestar

Why is it that we we feel ourselves to be watching a screen from inside our heads? We feel ourselves to inhabit the blackness in front of the light. One reason for this is because we talk to ourselves and, and possibly something else, in the this darkness. It has been demonstrated that East Asians are far less likely to engage in self speech at least while attempting to solve problems (Kim, 2002). Further Japanese deities and arguably the other of the Japanese self is felt to be something that watches from without (Heine et al. 2008). I notice that some of the best of them such as Naruto and hachimaki headband wearers may even have their names, or marks, not inside them, but upon their their foreheads like Rev 22:4. None of this muttering in the dark for them. In Japan the names are out there. I think that Japanese engage in tourism to "named places" to remind themselves of this fact.

The Japanese are Westernising furiously but it seems to me that the next stage in human development should be for the world to become Japanese, who are "meek" to boot. Bowie developed a mark for his last record. He nearly got there.

Image is drawn by me but the character is copyright Masashi Kishimoto, Hayato Date and Shueisha.

Heine, S. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 879–887. Retrieved from www2.psych.ubc.ca/~heine/docs/2008Mirrors.pdf

Kim, H. S. (2002). We talk, therefore we think? A cultural analysis of the effect of talking on thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 828. Retrieved from labs.psych.ucsb.edu/kim/heejung/kim_2002.pdf

Labels: japanese culture, tourism, 日本文化

Thursday, January 21, 2016

Henro: Sightseen Tourism and Pilgrimage

Labels: autoscopy, blogger, Flickr, Nacalian, nihonbunka, tourism, 日本文化, 観光

Thursday, July 02, 2015

A You for You and An Eye for an Eye

One of the simplest Nacalian transformations that I have yet to fully expand upon, is that of Mori Arimasa's theory of the Japanese first person pronoun. I have said most of this before, but I have not yet expressed the the rather bemused way in which Japanese view Western faces, or how we should conceptualise our faces in a Japanese frame of mind.

Mori argued that the Japanese first person pronoun is expressed in a variety of forms, in a variety of forms of language that always binds it into binary relationships with its interlocutor you, such that, expressed in a French frame of mind, the meaning of "I" in Japanese is merely "a you for a you" (汝の汝).

One half of Nacalian transformation of Mori's theory has, and had, already been argued by Lacan. Lacan argued that infants identify first with mirror images and as they mature, with their the first person of their self narrative. This progression is inevitable and desirable, Lacan claims, since in the "mirror stage" humans are locked into binary relationships with mirrors and others since the face is only face for another face, or rather in the same way that the Japanese I is (according to Mori, who was surely influenced by Lacan) another interlocutor for its interlocutor, the Western face is locked into a relationship with its 'visual interlocutor' or spectator. The Western face is in other words, just an eye for an eye. Just as the Japanese only hear their first person pronoun through the ears of the second person that they are addressing, Westerners can only see our eyes via mirrors or through the eyes of another. Lacan and Mori (and Bakhtin, Mead, Freud etc) further argue that, in France at least, language provides a third person perspective enabling Francophones to have an I which is objective.

The missing part of this "Nacalian" (Lacan backwards) transformation is my assertion that in Japan, the face is not merely a visual interlocutor for another interlocutor but felt to be observed by a third person generalised other (Senken no Me, Otentousama) that frees the Japanese face, and persona or self, from dependence upon binary relationships.

In each case the achievement of these freedom comes at a price. First of all, we are no longer our true selves. And futher, Derrida and I (!) argue that this extra other, in the West "The Ear of the Other," is uncanny (unheimlich): something once familiar that is now horrific and repressed (Derrida, 1985, p33), repressed and horrific.

Bearing in mind that Western faces are like eyes for eyes, it should appear to the Japanese that our faces are dependent upon the binary relationship in which we find ourselves. Indeed this is the case that Japanese perceive Westerners as always making rather grotesque (oogesa na) "faces" (and gestures) whereas their own facial expressions incline towards remaining objective, and 'composed'.

Bearing in mind that the objective and subjective is reversed - that is to say that the power relationship between the visual and the linguistic is reversed - leads to world views turned inside out, with completely different notions of time, space, travel, tourism and morality.

I prefer the Japanese method of self-reflection since I believe that that vision is somewhat less prone to "spin" or the self-enhancement that Westerners are so good at, and because matriarchy is more natural and effective than patriarchy. Indeed, patriarchy seems to me to be a sort of deviant version of matriarchy, where men somehow worked out how to use some of the natural control methods of matriarchs.

Image: kajap.hypotheses.org/450

Labels: blogger, Flickr, japaneseculture, nihonbunka, self, tourism, 日本文化

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

殺生石

Labels: blogger, culture, Flickr, japanese, nihonbunka, tourism, 日本文化

Thursday, March 19, 2015

Provide all the Accoutrements of a Temple

This is a bell at Two Lovers Point in Guam. The management of this most popular iconic spot on the resort island of Guam are at least subconsciously aware that if you want Japanese tourists to come to your destination, then provide them with all the accoutrements of a pagan temple: a legend, something symbolic ideally natural, some good luck charms (locks), a place to leave votive offerings (the rails to leave love locks), a way of making non-linguistic noise either by clapping, or ideally by a bell (as pictured above), and an opportunity for autoscopy: a mirror or place to take a selfie. Tourism is secular pilgrimage.

Labels: autoscopy, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, tourism, 日本文化, 自己視

Thursday, December 11, 2014

Omotenashi may be Unwelcome and Unwelcoming

Labels: blogger, Flickr, nihonbunka, self, tourism, おもてなし, 日本文化, 自己, 観光

Friday, January 24, 2014

Logotherapy for Japanese Cancer Patients: What can tourists carry?

First of all I worry about the effectiveness of teaching self narrative in this situation for the reasons mentioned in a previous post. A Zen priest, a more traditional helping hand in the face of death, would be more inclined to encourage us not to narrate anything at all.

Secondly this highlights a problem I having with my understanding of the Western and Japanese self and tourism. Yes, narration is extremely important in the West -- *we* really are homonarrans 人言 -- but so also equally important is "the light". Western pilgrims and tourists tour to gaze (Urry, 2002) and name (Culler, 1988) the image (Turner and Turner, 1995; Boorstin, 1992) even though they believe that the image is a qualia (Jackson, 1986), in the mind. Why should anyone need to go anywhere to get something which they believe to be in their mind?

One way of answering this question may be to focus on what people believe themselves to "carry" (Frankl, 1962, p. pp. 56–57. quoted below). The standard Western (excepting Ernst Mach) understanding of images is as "qualia:" things in the mind. Western philosophers would have it that the "brave overhanging canopy" is something that we can, if not fold up, carry around. If we do "carry" it, then it stands to reason that Mary (Jackson, 1986) and Western tourists should have to travel to get images, and carry them back.

Likewise, that the Japanese can and do travel to places with names, named-places (名所), where there is often absolutely nothing to see (Hiraizumi, ganryuujima, kokufunoato) and other "ruins of identity." (Hudson, 1999; Plutschow, 1981)

Japanese name-places provide names, they are fountains of names. The Japanese tourists provide the images, of themselves (the ubiquitous Japanese tourist selfie or kinen shashin 記念写真) and through their imagination, and often quite physically carry, yes, carry the names back home, in the form of sacred tags (お札) stamps, from the ”stamp rally,” pilgrimage, such as to Shikoku's temples or Ise shrine, often for other people (代理参り).

Since Westerners tend to believe in a "super-addressee" (Bakhtin, 1986) I think that we believe also that words, names, or at least what they refer to -- meanings, ideas -- are somehow omnipresent. Words are transmitted, by morse code or telephone but what they mean somehow manages to get there, be recreated in the mind of the recipient, faster than the speed of light, because it is as if all the meaning is already in the recipients head already. To someone who believes in the super-addressee it is impossible to carry a word, in its full sense, anywhere.

To explain the difference between Western and Japanese tourism I may need to focus less on the question, "What am I?" to "What can I carry?" What can we carry? Names? Images?

When we die, is it true as the saying goes, "You can't take it with you"? When we die, can we only carry what we are? I have noted that "people of the book" live on as words because they are in the book, and that Japanese believe that the dead become balls of light.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. (V. W. McGee, Trans., C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Eds.) (Second Printing.). University of Texas Press

Boorstin, D. J., & Will, G. F. (1992). The image: A guide to pseudo-events in America. Vintage Books New York.

Culler, J. D. (1988). The Semiotics of Tourism. In Framing the sign. Univ. of Oklahoma Pr.

Frankl, V. E., & Lasch, I. (1962). Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotheraphy. A Newly Rev. and Enl. Ed. of From Death-camp to Existentialism. Beacon Press.

Hudson, M. (1999). Ruins of identity: ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands. University of Hawaii Press.

Jackson, F. (1986). What Mary didn’t know. The Journal of Philosophy, 83(5), 291–295. Retrieved from www.philosophicalturn.net/intro/Consciousness/Jackson_Mar...

Plutschow, H. (1981). Four Japanese Travel Diaries of the Middle Ages. Cornell Univ East Asia Program.

Turner, V., & Turner, E. (1995). Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture (0 ed.). Columbia University Press.

Urry, J. (2002). The Tourist Gaze. SAGE.

An expert from Victor Frankl's "Man's Search for Meaning: An introduction to Logotherapy" which is quoted on Frankl's wikipedia page:

"We stumbled on in the darkness, over big stones and through large puddles, along the one road leading from the camp. The accompanying guards kept shouting at us and driving us with the butts of their rifles. Anyone with very sore feet supported himself on his neighbor's arm. Hardly a word was spoken; the icy wind did not encourage talk. Hiding his mouth behind his upturned collar, the man marching next to me whispered suddenly: "If our wives could see us now! I do hope they are better off in their camps and don't know what is happening to us."

That brought thoughts of my own wife to mind. And as we stumbled on for miles, slipping on icy spots, supporting each other time and again, dragging one another up and onward, nothing was said, but we both knew: each of us was thinking of his wife. Occasionally I looked at the sky, where the stars were fading and the pink light of the morning was beginning to spread behind a dark bank of clouds. But my mind clung to my wife's image, imagining it with an uncanny acuteness. I heard her answering me, saw her smile, her frank and encouraging look. Real or not, her look was then more luminous than the sun which was beginning to rise.

A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth – that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which Man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of Man is through love and in love. I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved. In a position of utter desolation, when Man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way – an honorable way – in such a position Man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment. For the first time in my life I was able to understand the meaning of the words, "The angels are lost in perpetual contemplation of an infinite glory."

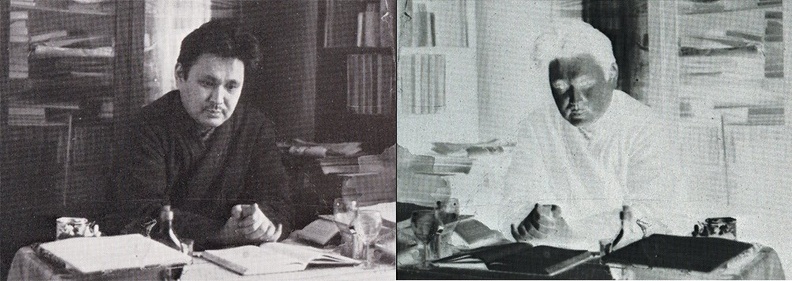

Photograph and Text copyright R. Kawahara, and Asahi Newspaper and image rights belong to Dr. K. Yamada.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, Nacalian, nihonbunka, tourism, 日本文化

Wednesday, April 03, 2013

Tourism as Reconstruction: What is unmoving in Cherry Blossom viewing?

Derrida "deconstructs" Western philosophy so it may fair to say, conversely, that the polemic that Western philosophers indulge in should be called the ongoing process of "reconstruction."

Western philosophers use polemical sleights of hand to convince us that all is well, and dualistic, in the world. Western philosophers draw our attention to defective signs, such as writing, "speech acts", "indicative signs," to assure us that there are good and proper signs that are dual, that come laden with, co-present with meaning, with "ideas". In so doing these nervous philosophers assure us and themselves that the act of hearing ourselves speak is not a gollum auto-crooning in the darkness, but a meaningful "expressive act."

This philosophical polemic is one example of "reconstruction," of the narrative-self. But is is not only philosophers who indulge in this sleight of hand. We are all to an extent a little perplexed by the whole speaking-to-ourselves thing. We are all a little worried about the existence of the meaning, "ideas" and the self as idea, and we all want therefore to indulge in a little self-reconstruction, to assure ourselves of our own selfiness.

Tourism is reconstruction par excellence. As Jackson's Mary-who-knows-no-red (Jackson, 1976) convinces philosophers of duality, the tourist who had never seen Breton clogs, is convinced of the existence of the idea by, in the act of discovering them. Look, there is Frenchiness (Culler)! Western tourists go to see the sights, to gaze, at that redness, that cultural icon which, hithertoo, existed for them only as an idea.

Japanese tourists, Zen though they may be, travel to indulge in reconstruction too, except they want to believe in non-duality, and the self as that place (場所, Nishida) where mind and matter meet. Just as Westerner tourists go to gaze at things for which they only had ideas and in doing so prove that the image is out there, Japanese tourist go to places where there are signs for which they only had images, where they allow their imagination to run riot in the mirror of their mind. Japanese also visit sites where they can experience the unfolding of time ("differance"), in order to return themselves to the purity of the mirror, which is the only thing that remains, un-moving, in cherry blossom viewing.

People travel to experience and expunge that which they visit and leave behind. Western tourists go to gaze (Urry) and leave the world of sight. Japanese tourists go to expunge those names, and expunging duality and time, enter the liquid world of light.

Jackson, F. (1986). What Mary didn't know. The Journal of Philosophy, 83(5), 291-295. http://118.97.161.124/perpus-fkip/Perpustakaan/Perpus%20Cero/Filsafat/Filsafat%20Modern/Materialisme%20Modern.pdf#page=199

Labels: japan, japanese culture, tourism, 日本文化

Friday, January 18, 2013

Useless Japanese Services

- Sales staff talking one octave higher than they would otherwise.

I don't want people to demean themselves to the extent of talking in a falsetto voice. - Petrol Station (Gas stand) attendants. Fortunately these are now seen less and less, due to changes in the law which now allow drivers to fill their own tanks. Having someone do it for you, while you wait in the car watching them do it, adds unnecessarily to the cost of petrol. Like the people waving flags on each approach of roadworks compulsory gas station attendants may have been a way of ensuring full employment.

- Sales staff putting out their hand to allow you to deposit refuse into it (pass me a bin please)

- The cries of "someone has ordered XYZ" (XYZ icchou), or "someone wants an extra serving ("okaidama") in Japanese restaurants and otherwise announcing what you have ordered to the rest of the restaurant),

- Snack hostesses and other providers of conversation that one must pay for.

- Photo-me machine booths (purikura) everywhere with the ability to add annotations and to make ones eyes bigger (more Caucasian?).

- Surgery to add a crease to upper eyelids or make ones nose longer.

- Traditional Japanese hotel (ryokan) waitresses (nakaisan) that tell me how, and in what order, and which sauce to eat my food, and even when to go to bed.

- Supermarket workers that escort you to produce you ask the whereabouts of rather than tell you what isle the produce is sold in, because I usually want to weave my way through the store rather than be escorted to the far side of the shop.

- All the till receipts even when your hands are full of shopping and change (which is generally used as a paper weight)

- Wrapping and more wrapping (some convenience store workers seem to find it difficult to put a niku-man on my hand, perhaps they fear I will be burned),

- The attempts at English even when I am speaking in Japanese,

- Offers of disposable chopsticks (which are supposed to be easier to use than regular ones)

- The instance upon providing (and requiring me to bring) a card particular to each hospital or clinic

- New years cards from various service industries

- Taxi doors (I have to remember not to annoy drivers by shutting my door and hitting them with their handle)

- Tiny indoor slippers that I can't get my feet into

- A little bit of food, called tsukedashi, that I have to eat and pay for to drink a beer

- Phones that don't accept or allow me to change SIM Cards

- Banks and post offices that insist upon providing receipts (if you try to do a runner, they run after you)

- All the advertisements inside my newspaper

- The wrapping for the newspaper on rainy days though our postbox is a box and under our porch

- Book covers and book "belts"

- Toothpicks

- Being thanked by vending machines,

- Ice in bar urinals,

- Purposefully adding extra froth on my beer,

- Bits of plastic fairing around the windows of cars,

- Mammoth exhaust pipes on cars, the whole car "meiku" (in the sense of make up, or cosmetics) after-parts industry,

- Umbrella condoms when an umbrella rack would do fine since umbrellas are so cheap they are almost free and the Japanese do not steal things anyway

- Surprise packs of things I do not need sold on New Years Day by department stores,

- Department stores or shops that are able to sell things at inflated prices due to the fact that they are prestigious shoppers and can provide wrapping that indicates their prestigiousness.

- Being greeted with a bow if I am one of the first customers arriving in the morning.

- The ceaseless announcements of things that are utterly obvious ("do not bring dangerous things onto the train"),

- Car park attendants that wave me in directions that I already knew I wanted to go in,

- Public service sirens to call me home to lunch and dinner,

- Cardboard toilet paper tubes with printing thanking me for having finished the toilet paper,

- Toilet seats that blow dry my posterior,

- Free muck brown tea in canteens that tastes like it was produced by a goat,

- Politicians with no policy just a loud Tannoys.

- Individually wrapped fruit,

- Square water melon,

- The opportunity to taste sausages in supermarkets (unless this is an opportunity for free food, which it is not. It is an attempt to make customers to feel obligation or giri to return the favour).

- Horrible looping background music in shops such Yamada Denki and Mr Max

- Sales staff that ask me to sit down. I would often rather stand and when I want to sit down, since I am not a dog, I do not need to be asked to sit down.

- Noise producing devices to hide the sound of my excrement falling into toilet bowls. Admittedly these are only generally provided only to women.

- Supermarket cash register staff that repack shopping into baskets as opposed to into bags to take home as in the UK. They carefully position the heaviest items at the bottom of the basket making putting the same items at the bottom of ones bag difficult.

- Being asked to confirm the brand of cigarettes that I order from behind the counter in convenience stores two or three times.

- The little piece of plastic grass in bento lunch boxes.

- Theme parks replicating areas of foreign countries such as Huis Ten Bosch, Parke Espana, and Shakespeare Country Park.

- Restaurants and hotels which could easily provide a view but do not, such as Sea Mart in Hagi, which is almost beside the sea but provides a view of the back of some warehouses obscuring the sea front.

- Tourist attractions which are places where something once happened, but are now only an empty field with a commemorative stone to mark the spot.

- Being able to see the car or person I am controlling in Japanese video games such as MarioKart.

- Female staff who clean the gents while I am using them.

- Sales staff, such as at DVD rental stores that pass things to me in their scripted order, rather than putting them on the counter requiring me to keep standing their proffering a bag of DVDs or to accept all the things the are passing before I have put the other things away.

- Telephone service staff that use all sorts of polite padding and take ages to get to the point.

- Telephone service staff that insist upon putting me through to the appropriate staff member when my question is so simple as to be answerable by anyone and therefore forcing me to ask my question again.

- In spite of, or as exemplified by performing various demeaning services that I do not ask for, the general patronising superciliousness of service staff who stick to their scripts and praxes rather than submitting to being my willing servant.

- The general tendency of service staff to attempt to provide what is required as indicated by non-verbal communication rather than listening to my commands, which I find myself repeating, like the brand of my cigarettes, two or three times.

- Elevator girls that press the buttons of elevators in departments stores and announce what is available on each floor. Now largely a service of the past.

日本語版

Labels: japan, japanese culture, tourism, 日本文化

Wednesday, November 07, 2012

The Effect of Social Support on Americans and Japanese

I like this paper and consider it relevant to those in the hospitality industry. When I first came to Japan, being a Westerner of low self-esteem, I did not like the way that Japanese hospitality providers would provide me with English language menus, forks or disposable chopsticks, since I felt that their kindness was saying, "you can't read Japanese," "you can't use ordinary chopsticks." I felt their kindness was an attack upon my self-esteem and independence. So, beware of helping Westerners. Some of them, are hinekureteiru or twisted.

At the same time, if the Japanese tendency to try to help prior to any demand (sasshi) is explained first, Japanese style hospitality, such as that provided by traditional inns (ryokan) providing luxury but choice-less food (kaiseki) with mothering helpers (nakai) can be a very rich cultural experience.

Bibliography

Uchida, Y., Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., Reyes, J. A. S., & Morling, B. (2008). Is Perceived Emotional Support Beneficial? Well-Being and Health in Independent and Interdependent Cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(6), 741–754. doi:10.1177/0146167208315157 Retrieved from faculty.washington.edu/janleu/Courses/Cultural%20Psycholo...

Labels: care-givers, collectivism, individualism, japanese culture, nihonbunka, tourism, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

The Fabric of the Universe: Made of the Logos or Made of the Light?

The Japanese feel they can copy shrines, horses, food, and foreign countries in form of the popular foreign villages (gaikoku mura. See Graburn, Ertl, & Tierney, 2010; Hendry, 2000, 2005). Perhaps all this 'copying' started with a special mirror. With regard to shrines at least the Japanese claim it is not copying, but like "dividing a fire" (Norinaga see Herbert, 2010, p99) .

At least, when the Japanese see these "copies" they feel they are experiencing the same thing an authenticopy, or Simulacra (Baudrillard, 1995). I argue that they are the same thing to the Japanese because the world is the light. To borrow Heisig's words, the Japanese (or at least Nishida) believe the world meets the self at the plane of that "tainless mirror"(Heisig, 2004).

One can tell that the "copying" is visual because, for instance, the Japanese often like to change the size (Lee, 1984) or taste (Graburn, Ertl, & Tierney, 2010, p. 231) of the "copies". This matters not one bit in the plane of the mirror, where there is no size; get up close to a Bonsai and it could be a massive tree.

Westerners feel that the meanings behind their words are replicated in the minds of others (Nietzshe, 1888; Derrida, 2011) because the world, for Mary (Jackson, 1986), Dennet (2007) and I at least, is made of Logos: our dream of language made real. Occasionally some of us get out of our room and see the light, which makes us shiver.

So who are the copyists now, the word copiers or the light copiers?

Imai & Gentner (1997; see Imai & Masuda, in press or Genter & Boroditsky, 2001) showed Japanese and American children and adults, an image like the above. My version shows a half-moon shape made of plasticine and red playdough, and some lumps of plasticine. In the original experiment the subjects were told that the thing at the top was a "dax" and to bring the experimenter another dax. The Japanese were more likely than Americans to bring the pieces of plasticine. This is not surprising in view of the fact that Japanese nouns do not have plurals and need counters to refer to number, as English does for materials. The Japanese seem to be seeing the world as materials.

But then later Imai and her associates performed the same experimenters tried getting Americans (Imai & Gentner, 1997) and then Japanese (Imai & Mazuka, 2007) to "bring the same as this," again pointing to the green shape at the top, without giving that thatness a name.

Without a name, both the Americans and the Japanese were more likely to behave like the Japanese choosing more green plasticine rather than the red shape or entity, because they have got the words out of their heads to an extent. Imai interprets the data in a different way specifically rejecting the "perceptual" hypothesis. But I claim that deprived of words for a novel experience, both Americans and Japanese had started to see the light - or the colours that we anticipate Mary will enjoy so much - a little more clearly - hence the choice of plasticine rather than the half moon shape.

The floating world, the one that the Japanese believe in at the same time know (or are told) does not really exist is often referred to as "colour" (shiki) in Japanese Buddhism.

Being presented with these novel shapes is perhaps like a little journey, a minor tourism experience where the Japanese tourist wants to be given the name first, whereas the Western tourists wants to go and see the sights and give it a name afterwards.

Bibliography (thanks Zotero)

Baudrillard, J. (1995). Simulcra and Simulation. (S. F. Glaser, Trans.). Univ of Michigan Pr.

Dennett, D. (2007). What RoboMary Knows. Phenomenal Concepts and Phenomenal Knowledge: New Essays on Consciousness and Physicalism, 15–31.

Derrida, J. (2011). Voice and Phenomenon: Introduction to the Problem of the Sign in Husserl’s Phenomenology. Northwestern Univ Pr.

Genter, D., & Boroditsky, L. (2001). Individuation, relativity and early word learning. In M. Bowerman & S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development (pp. 215–256). Cambridge University Press.

Lee 李御寧. (1984). 「縮み」志向の日本人. 講談社.

Graburn, N., Ertl, J., & Tierney, R. K. (2010). Multiculturalism in the New Japan: Crossing the Boundaries Within. Berghahn Books.

Heisig, J. W. (2004). Nishida’s medieval bent. Japanese journal of religious studies, 55–72. Retrieved from nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/staff/jheisig/pdf/Nishida%20Medieval%...

Hendry, J. (2000). Foreign Country Theme Parks: A New Theme or an Old Japanese Pattern? Social Science Japan Journal, 3(2), 207–220. doi:10.1093/ssjj/3.2.207

Hendry, J. (2005). Japan’s Global Village: A View from the World of Leisure. A Companion to the Anthropology of Japan, 231–243.

Herbert, J. (2010). Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. Taylor & Francis.

Imai, M., & Masuda, T. (n.d.). The Role of Language and Culture in Universality and Diversity of Human Concepts. Retrieved from www.ualberta.ca/~tmasuda/ImaMasudaAdvancesCulturePsycholo...

Imai, M., & Mazuka, R. (2007). Language-Relative Construal of Individuation Constrained by Universal Ontology: Revisiting Language Universals and Linguistic Relativity. Cognitive science, 31(3), 385–413.

Imai, Mutsumi, & Gentner, D. (1997). A cross-linguistic study of early word meaning: universal ontology and linguistic influence. Cognition, 62(2), 169–200. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(96)00784-6

Imai, Mutsumi, Gentner, D., & Uchida, N. (1994). Children’s theories of word meaning: The role of shape similarity in early acquisition. Cognitive Development, 9(1), 45–75. doi:10.1016/0885-2014(94)90019-1

Jackson, F. (1986). What Mary didn’t know. The Journal of Philosophy, 83(5), 291–295.

Nietzsche, F. (1888)“Reason in Philosophy.” Twilight of the Idols. transl. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale. Retreived from http://www.handprint.com/SC/NIE/GotDamer.html#sect3

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, Shinto, specular, theory, tourism, 日本文化, 神道

Monday, May 21, 2012

Double Dreams in the Floating World

As the juxtaposition of movement and immobility in this image suggests, motion is, in a sense, the antithesis of order: it displaces what ought to stay put; it frees what ought to be contained." (p 187-188. Image on page 189, emphasis mine.)

Bearing in mind her subject matter - Japanese travellers who go to see sights where there is nothing to see - this is a fabulous choice of image to close with. Prof Nenzi is on the money, but I wish she had spilt a little more ink, at least in the interrogative. Do "collective" dreams exist? Can we share our dreams like these dreamers, in some way, in any way? Why are these Japanese dreamers dreaming autoscopically (Masuda,Gonzalez, Kwan, Nisbett, 2008; Cohen and Gunz, 2002) each seeing the image of themselves in their own dream - the dream is doubly double? From whose perspective is the dream seen? Perhaps the most important question for a theory of travel is, have the dreamers seen mount Fuji? And the million dollar question, bearing in mind the genre of the artwork, when they wake up will the erstwhile dreamers then share the same picture of the floating world.?

To be honest I can't answer these questions for myself let alone the Japanese. But at least, I think that there is considerable cultural difference at least in degree, and that these differences help explain cultural differences in travel behaviour.

The position of these (as Nenzi notes) sexually ambiguous lovers, reminds me of the cover of "The Postcard." (Derrida, 1987) which I consider to have been self, or intra-psychologically addressed. It is also reminiscent of the many pictures of the floating world that Kitayama (2005) uses to illustrate the, he argues, psychologically important trope of "looking together." Furthermore, if the Japanese are capable of autoscopy even when awake ( as my research, Heine, et al., 2008, shows), the picture may be illustrative not only of Japanese travel behaviour, but also of the Japanese self".

Image credits: Isoda Koryuusai, Dreaming of Walking near Fuji, 1770-1773. Woodblock print, ink and color on paper, 19.1 b 25.4cm. M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (The Anne van Biema Collection, S2004.3.23)

Bibliography Created by Zotero

Cohen, D., & Gunz, A. (2002). As seen by the other...: perspectives on the self in the memories and emotional perceptions of Easterners and Westerners. Psychological Science, 13(1), 55–59. Retrieved from web.missouri.edu/~ajgbp7/personal/Cohen_Gunz_2002.pdf

Derrida, J. (1987). The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. (A. Bass, Trans.) (First ed.). University Of Chicago Press.

Heine, S. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 879–887. http://www2.psych.ubc.ca/~henrich/Website/Papers/Mirrors-pspb4%5B1%5D.pdf

Kitayama, O. 北山修. (2005). 共視論. 講談社.

Masuda, T., Gonzalez, R., Kwan, L., & Nisbett, R. E. (2008). Culture and aesthetic preference: comparing the attention to context of East Asians and Americans. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(9), 1260–1275.

Metzinger, T. (2009). The Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self (1st ed.). Basic Books. (I have not read this but it sounded like Nishida and uses the word "autoscopy" so it is on my reading list)

Nenzi, L. N. D. (2008). Excursions in identity: travel and the intersection of place, gender, and status in Edo Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

Labels: autoscopy, image, japan, japanese culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, theory, tourism, 日本文化, 自己視

Wednesday, May 16, 2012

Empire of the External Signs: Travelling to Sight and Symbol

Not only when on holiday, but also when having fun as a child, the Japanese like to collect symbols. They are modern totemists, they "bricole."

Levi-Strauss in one of his last formulations defined those "primities" that have a "savage mind" -- the "bricoleurs", the botching, DIYers, that think with signs-they-have-to-hand (Levi-Strauss, 1966) -- as those that do not have writing.

"The way of thinking among people we call, usually and wrongly, ‘primitive’—let’s describe them rather as ‘without writing,’ because I think this is really the discriminatory factor between them and us" (Levi-Strauss, 1978, 5)

What he meant to say was that they do not have an alphabetic writing (see the brilliant paper by Chad Hansen, 1993, "It started with Phoneticians").

The important point is not the natural constraint that Levi-Strauss proposes that "savages" face. Like the Japanese, even the totemists in totemistic societies that Levi-Strauss himself reported, had started to create their own totems (e.g. gourds, mythical animals) and are not constrained by nature.

The important point, that Derrida stress(1998), is that the "savages" remain aware of the corporeality of the sign, aware of the "trace," they remain forever "post-modern," even more so than Derrida who claims phonocentrism is inevitable, and unable to believe in "presence" of meaning, of voice as thought. The "savage" (or perhaps savant) is aware that the sign is external.

They, the Japanese, are happy to travel, to the shrine, to the local toy shop, to the "named place" (meisho) abroad to collect external signs.

Derrida, J. (1998). Of grammatology. (G. C. Spivak, Trans.). JHU Press.

Hansen, C. (1993). Chinese Ideographs and Western Ideas. The Journal of Asian Studies, 52(02), 373–399. doi:10.2307/2059652

Levi-Strauss, C. (1978). Myth and Meaning. Routledge.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966). The science of the concrete. In G. Weidenfield (Trans.), The Savage Mind. University Of Chicago Press.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, mirror, occularcentrism, reversal, specular, theory, totemism, tourism, 日本文化

What Mary didn't Know, but the Japanese Tourist did

There are a number of theories of why tourists tour. The most famous four are perhaps those by Boorstin (1992), MacCannell (1976), Turner (Turner & Turner, 1995) (for a summary of these see Cohen, 1988), and Urry (2002). Culler's extended semiotic analysis (1988) of tourism is also well recommended.

Boorstin, in his book "The image: A guide to pseudo-events in America" (1992 [1961]), characterised the tourist as an inferior traveller, satisfied with "pseudo events" or in his word, images.

MacCannell's (1976) analysis positions the tourism as a religious (after Durkheim, 1965) activity that through the interpretation of signs (Barthes, 1972, 1977), allows the alienated (Marx, 1972) proletarian tourist to gain a picture of society as a whole, thanks to the presentational (Goffman,2002) activities of tourism providers. Rather than being happy with "pseudo-events", the tourist seeks authenticity. The apparent "pseudo event" status of the tourist experience is, MacCannel argues, merely an inevitable consequence of the structure of presentation and the sign, as Culler explains in more detail (1988).

Drawing upon a considerable oeuvre of anthropological research Turner (Turner and Turner, 1978) also sees the tourist as in search of a sense of wholeness, but in a less intellectual, more chaotic, ecstatic, "liminal" merging or communitas, as a result of the sacred or sacrelized images (a notion shared by MacCannel).

Urry (2002), turning back towards Boorstin while drawing on Turner, argues that authenticity is by no means an essential part of tourism. Tourism for Urry is "more playful" (p.11), and quoting Fiefer (1985) even allows for 'post-tourists' who are aware of the inauthentic nature of the sight, which is sometimes even virtual, but enjoy themselves anyway.

So, perhaps the most obvious controversy in tourism research is whether "authenticity" is required by tourists and if so in what sense? At one end of the extreme, one may wonder if someone watching a travel program on TV a (post) tourist? Surely not. But, when Urry's alienated telephone switchboard operator goes to see the Statue of Liberty, and sees in that sacralized site the meaning of her life, her work, and her society, in the support of the freedom there represented, does it matter that the statue in New York is a replica of then one in Paris? Would it matter if she were watching one of the many replica statues of liberty adorn Japanese "Love Hotels"(Cox, 2007, p224)? Or indeed if the receptionist were herself Japanese, or Russian in the Stalinist era, would her experience of that "freedom" still be authentic - teaching her by contrast the meaning of her arguably un-free life? Many of MacCannell's examples are of domestic US tourism, but as he points out that international tourism can teach us about ourselves through the comparisons we make between our own and other cultures, comparisons without which we would not be aware of our own culture at all.

Contra MacCannell however, we must at least accept Urry's assertion that in tourism, *kitsch abounds*.From Butlins, to Coney Island and on to Tokyo Disney Land (referred to as "rat" by some Japanese school children), tourist experience are often wallowing in kitsch, simulations, and "pseudo-events." And yet, even so, when a child sees Mickey, where-ever she sees Mickey, should we deny that some sort of experiential authenticity takes place? I will return to this point, but, first focus on the characteristic of tourism that the above theorists appear to share.

While there is some disagreement as to the "authenticity" of the tourist experience, all of these theorists stress the importance of the image and gaze. Tourism is sight-seeing, tourists go to gaze at images. The important praxis for tourists is above all to gaze.

But of course tourists do not only gaze. Far from it. As MacCannell and Culler point out, tourists are semiotics (Culler, 1988, p2.), theorists ((Van den Abbeele, 1980, reviewing MacCannell) or ethnologist (Culler, 1988, p11). Typically, they go to gaze at sights, the more unusual and out of their normal frame of reference the better, so long as they they are able to judge them authentic "That is Frenchiness,"(Culler, 1988, p2) "That is a Gondola," "It's Mickey!" Ethnography is a profession, but giving things, new things, names, is the one work that was required of Adam in the Garden of Eden before the fall. Tourists love to see new things, and yet, already know and say what they are. They go in search of these "translations" from sight as sign, to linguistic symbol or meaning.

Readers (not that I have any) that recognise the reference in my title will know where I am taking this but first, in order to gain a clearer picture of tourism, it will help to look at it from comparative perspective, from the gaze of the Japanese tourist. In order to introduce the Japanese tourist gaze, consider a type of tourism that most Western theorists consider to be exceptional.

MacCannell argues that for a sight to be sacralized markers (such as signs, maps, and viewing platforms) are set up, and at times these markers can become the central focus of the tourism destination. Likewise, Urry (2002, p13) citing Culler (1981, p139)

"Finally, there is the seeing of particular signs that indicate that a certain other object is indeed extraordinary, even though it does not seem to be so. A good example of such an object is moon rock which appears unremarkable. The attraction is not the object itself but the sign referring to it that marks it out as distinctive. Thus the marker becomes the distinctive sight (Culler,1981: 139). "

It is precisely these exceptions, that I think form the norm of Japanese tourism behaviour: Japanese tourists typically go to see "markers". Japanese tourism consists in is purest most characteristic form in the visiting and collection of markers.

Most Western tourism theorists agree that tourism is about seeing. People go to places to gaze (Urry, 2002) at images (Boorstin). Even the most semiotic of analyses (MacCannell, Culler) has (Western) tourists go to sites where they apply "markers" (guidebooks, signs, labels) to sights. Very occasionally MacCannell notes, such in the case of a piece of moonrock, the labels maybe of more interest than the sights themselves.

The Japanese have been going to see markers since time immemorial. The author of Japan most famous travelogue - The Narrow Road to the Deep North - went to see "Ruins of Identity" (Hudson) Matsuo Basho, places were once great things happened but where now there is no trace even of ruins, only the markers (such as a commemorative stone) remains. Basho wrote a poem and wept. This trope is continued in other Japanese travelogues, and tourism behaviour, which is often described as being "nostalgic".

This "nostalgia" is sometimes thought to be a reaction to Westernization, but it has clearly been going on for a lot longer. The Japanese have been waxing lyrical about ruins, since the beginning of recorded time. This practice originates in Shinto. Shinto shrines and visiting them - the central praxis of the Shinto religion - are themselves ruins, markers to events that, supposedly, took place in the time of the gods.

The first Tourist attraction that Matsuo Basho visitied Muro no Yashima, is a shrine to the a god that gave birth to one of the (divine) imperial ancestors in a doorless room (Muro) which was on fire. It has since been traditional to use the word "smoke" (kemuri) in poems about that location.

The Japanese worship markers. In Japan the sign has fully present and evident corporeality.

I thought at first that the Japanese were going to names to provide the sights, the images. In these days of television, sight is as portable as information. While (as described below) Westerners are inclined to believe in the spooky immateriality of the sign (used as they are to talking to themselves in the "silence" of their minds) so the thought of traveling to a sign is probably not very attractive. Signs are everywhere and no-where. Signs are within. We travel to see "it" that thing out there "with our own eyes".

But for the Japanese signs have to be transported. The first of these, the Mirror of the Sun godess was transported from heaven, to be the marker of the most important deity. The imperial ancestors then distributed mirrors to the regional rulers and some of these were enshrined. Subsequently Japanese gods have been be stamping their names on pieces of paper and being transported all around the country to be enshrined far and wide.

The Japanese do not travel for sights but for markers and since markers are portable, then one might think that it would be the Japanese that might stay at home. Why don't they set up a marker saying Paris and visit it instead? This is indeed what they do. As Hendry points out, throughout Japan there are markers to places abroad, Spanish towns, Shakespeare's birthplace "more authentic than the original!" (Hendry's exclamation mark). If the marker has been transported, and the sights have been provided, then the Japanese are happy to visit that transported marker instead, or in preference to the original. "Foriegn villages" (gaikoku mura) have a tremendous history stretching back as far as their have been shrines but more recently, again, the first tourist attraction that Matsuo Basho visited, as well as being associated with the actions of the gods, was also "the shrine of seven islands." In the grounds of the Muro no Yashiam (Room of Seven Islands) shrine there are miniature version of eight other shrines all around the country (in those days abroad). In other words, Basho's first destination of call was a "foriegn village." Likewise as Vaporis elucidates the most popular site in the Tourism City which was Edo (the place which all feudal lords had to travel to, the place with the most famous sites and still today the most visited place in Japan: Tokto) was Rakan-ji a temple in which all of the 88 Buddha statues of a famous pilgrimage were collected together. As if going to an international village, by going to that one temple, the Japanese were able to feel that they had completed a pilgrimage in the afternoon. The 88 stop pilgrimage has itself been copied into many smaller, pilgrimages all around Japan, sometimes at a single temple, including at my village of Aio Futajima. In sort of nested copying, the copied 88 sites of the larger pilgrimage are themselves copied to one of the temples where again, one can complete the pilgrimage at one visit.

The Japanese are also fond of post-tourism via the use of guidebooks and maps, which are like super-minature "foreign villages."

Taking a deconstructive turn, I associate the Western practice of going to see sights, such as Frenchyness and proclaiming them Frenchy, with the ongoing efforts of Western philosophers to promote dualism (Derrida). Derrida argues that the dualisms of mind and body, or thinking matter and extendend matter, locutionary and illoluctionary acts, speech and writing, etc, are all designed to purify the habit of listening to oneself speak, to frame this habit as thinking. As other deconstructive criticism has argued, the creation of dualities does not only take place at the Philosophers' desk but also in pictorial art, literature, mythology (Brenkman) and society. If the philosophers are interesting it is because they give us clues of to the tactics by which dualities can be preserved. One of the most recent such tactics is that provided by Jackson in his papers regarding Mary in a black and white room.

Mary grows up in a black and white room. She sees the world through black and white monitors. She knows everything there is to know, physically, about the world except she has never seen colour. When she leaves here room and sees some red flowers, she is (we are persuaded) surprised. "Wow, so that is what red is." This demonstrates to somewhat there is something non-physical about the world. Even if one has all the data, all the information, all the language about the world, there is something about the sights, the seeing, the images, that makes us go wow, and proves that the world is not only physical. This thought experiment persuades some of duality.

Tourists are all Mary. They go in search of Frenchiness and in a mass transcendental meditation, they see Frenchiness, the Niagara falls, and are assured that there there is a world out there, and a private world in here.

But what of the Japanese? The seem to be going to see the marker, the sign saying "This is red." I had thought perhaps they they then provide the sight from their imagination to go with it. I.e. we go to sights to mark them, Japanese go to markers to site them. But this is not entirely the case. Yes, there is some "image provision" going on on the part of the tourists. Someone intending to visit the site of the famous duel between Miyamto Musashi and XYZ in the straits of Kanmon -another completely empty ruin of a tourist attraction - said that the the place brought up many images (omoi wo haseru). Someone taking a super miniature foreign village style-tour aroud a map of Edo said that just looking at the map brought back "the mental image of the Edo capital" (omokage wo shinobaseta).

But that is not what is going on in Japanese tourism as I found out this weekend. Before writing about Japanese tourism I thought it would be a good idea to do some, so I visited some of the J-Tourism style ruins in my local village and was powerfully impressed.

In the local town there is a ruin of an ancient governmental site from about 1200 years ago. All that remains is a field and some commemorative stones. There are benches lined up beneath the trees at one side of the site, in front of the empty field with some "markers" explaining what used to be in the field. Imaging the tourists rather than the ancient town hall, I could not but laugh out loud.

In my village of Aio, there are ten tourist attractions, two of which are empty. One is to the early twentieth century European style Japanese painter Kobayashi Wasaku. There is a bust. Two commemorative stones and an empty area of tarmac. And finally and most movingly, close to our beach house, on the road on the way there is the site of the birthplace of one of the Choushu Five, Yamao Youzou a young revolutionary, who was sent to study in my hometown, London, towards the end of the nineteenth century. He studied engineering in London and Scotland and came back to Japan to lead the Westernization of its technology education, founding what is now the engineering department of the University of Tokyo. At the site of his birth place there is a large black stone upon which there is a poem.

There is a poem which goes something like

At the end of a long journey

Which is the heart

Is Japan

はるかなる心のすえはやまとなる

Nothing beside remains. Laughing at myself all the while, I had a Matsuo Basho moment and cried. It was not that I imagined the figure of Mr. Yamao but, as was suggested to the readers of a modern guide to Basho's work, he traveled all over Japan to the sites visited by the ancient so as too "commute with their hearts" (kokoro wo kayowaseru) and that we by visiting the same sites, or just reading the guide book can do the same through the filter of Basho. By the same logic, can you feel my heart in the above photo?

The attraction of the small hillock next to a stone surrounded by bamboo it was not the sights, or the marker, nor the tourists gaze (my gaze), but the gaze of Mr. Yamao who had also stood there well before setting off to London, and back to change the world. I felt I saw the world through Mr. Yamao's eyes.

Had I imagined things, then I might have attempted to keep up the dualism between name and vision. On the contrary however this destination seemed to have been designed to make me feel the gaze of another, together. I will have to use Kitayama Osamu's gazing together theory too.

Bibliography by Zotero

Boorstin, D. J., & Will, G. F. (1992). The image: A guide to pseudo-events in America. Vintage Books New York.

Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies. (A. Lavers, Trans.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Barthes, R. (1977). Elements of Semiology. Hill and Wang.

Cohen, E. (1988). Traditions in the qualitative sociology of tourism. Annals of tourism research, 15(1), 29–46.

Cox, R. (2007). The Culture of Copying in Japan: Critical and Historical Perspectives. Routledge.

Culler, J. D. (1988). The Semiotics of Tourism. Framing the sign. Univ. of Oklahoma Pr.

Durkheim, E. (2001). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. New York: Free Press.

Feifer, M. (1987). Tourism in History: From Imperial Rome to the Present. Natl Book Network.

Goffman, E. (2002[1959]). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City, NY.

Heine, S. J., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 88–110.

MacCannell, D. (1976). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Univ of California Pr.

Marx, K. (1972[1844]). The marx-engels reader. WW Norton New York.

Turner, V., & Turner, E. (1995[1978]). Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture (0 ed.). Columbia University Press.

UN WTO. (2012). World Tourism Barometer: Volume 10. Advance Realease. Madrid: United Nations World Tourism Association. Retrieved from dtxtq4w60xqpw.cloudfront.net/sites/all/files/pdf/unwto_ba...

Urry, J. (2002). The Tourist Gaze. SAGE.

Van den Abbeele, G. (1980). Sightseers: The tourist as theorist. Diacritics, 10.

Labels: nihobunka, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, religion, theory, totemism, tourism, 日本文化

Wednesday, May 09, 2012

Collecting Symbols becoming a Dangerous Addiction in Japan

There is no financial reward to those that obtain the special symbols but the perceived value of these cards is so great that some Japanese are spending large amounts of money attempting to obtain them. This practice is called random-card-complete-set-collection or "conpugacha", and it has become an addiction. In the face of the dangers of this addiction, the Japanese government is thinking to impose restrictions on online game providers. The above article in today's Asahi newspaper reports the fears of online game providers in the face of proposed new regulations.

I suspect that the perceived value of the card - its fetishization - is at least in part in and of itself: the very act of collecting symbols is something that the Japanese find attractive since there is a long tradition of collecting symbols in Japan: from traditional sacred symbols (Yamada, 1965, 1966), pilgrimages (Reader, 2005), mass travel booms due to the belief that sacred symbols were falling from the sky (Nenzi, 2006) and stamp rallies (see Origin of the Stamp Rally), and various types of card and symbol collections for children (see Totem Badges Old and New).

At the same time the association of obtaining special symbols with interpersonal interactions (in this case in interactions in an online game community) is also found with more traditional symbols such as good luck amulets which are often an expression of love (Ayumu & Koshi, 2006) or perhaps a sort of assurance on the part of the giver (see Japanese Lucky Charm: Pubic hair). Often symbols give their holders the power to transform themselves, often including their appearance (see Transformatory Sacred Items Across the Ages).

For a long time the Japanese were thought to be "collectivists" because they travelled in groups, looking out the window when they reached the "named-place" (meisho). Today, the Japanese are more likely to travel on their own than Britons or Americans, but they still take with them their guidebooks (Goo Ranking, 2008), and travel to the named, symbolic places.

Ayumu, A., & Koshi, M. (2006). 「お守り」をもつことの機能 : 贈与者と被贈与者の関係に注目して[The function of having a ‘lucky charm’ : The relationships between donor and recipient]. Japanese Journal of Social Psychology ( Before 1996, Research in Social Psychology ), 22(1), 85–97. Retrieved from ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110004798371

Goo Ranking. (2008). 海外旅行先でついやってしまう「日本人ぽい」行動ランキング - 旅行ランキング - goo ランキング. Retrieved May 9, 2012, from ranking.goo.ne.jp/ranking /011/sightseer_pattern (based on a JTB survey)

Nenzi, L. (2006). To ise at all costs: Religious and economic implications of early modern nukemairi. Japanese journal of religious studies, 75–114.

Reader, I. (2005). Making pilgrimages: Meaning and practice in Shikoku. University of Hawaii Press.

Yamada, T. (1965). Shinto Symbols (Parts 1-5). Contemporary Religions in Japan, 7(1), 3–39.

Yamada, T. (1966). Shinto Symbols (Parts 6-8). Contemporary Religions in Japan, 7(2), 89–142.

Labels: japanese culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, religion, Shinto, theory, totemism, tourism, 日本文化, 集団主義

Tuesday, May 01, 2012

Nakatsue still Loves Cameroon

8 Years after Nakatsue Villiage, Oita Prefecture, hosted the Cameroon football team during the 2002 world cup, the villagers were still supporting the Cameroon team in its match against Japan, in the 2010 South African World Cup competition.

Not only does this prove Yuki's assertion (Yuki,2003) that Japanese do not engage in intergroup comparison, do not enhance their in-groups nor deride out-groups, but also it says something above Japanese hospitality. Anthropologists have argued that guests in rural villages in Japan are kept at a certain distance (Martinez, 1992; Knight, 1995), but at the same time treated with such respect they may even feel like gods (Martinez, 1996).In this case, visitors to this rural village are remembered and venerated even by those who are too young to have met them.

Bibliography created with a few clicks

Knight, J. (2007). Tourist as stranger? Explaining tourism in rural Japan. Social Anthropology, 3(3), 219–234. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8676.1995.tb00304.x

Martinez, D. (1992). Tourism and the ama: the search for a real Japan. In E. Ben-Ari & B. Moeran (Eds.), Unwrapping Japan: Society and Culture in Anthropological Perspective. University of Hawaii Press.

Martinez, D. (1996). The tourist as deity: ancient continuities in Modern Japan.

Labels: collectivism, japanese culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, tourism, 日本文化, 集団主義

This blog represents the opinions of the author, Timothy Takemoto, and not the opinions of his employer.