Saturday, November 11, 2017

The Heart of Yamato

Takemoto, T. R., & Brinthaupt, T. M. (2017). We Imagine Therefore We Think: The Modality of Self and Thought in Japan and America. 山口経済学雑誌 (Yamaguchi Journal of Economics, Business Administrations & Laws), 65(7・8), 1–29. Retrieved from nihonbunka.com/docs/Takemoto_Brinthaupt.pdf

Labels: japanese culture, mirror, Nacalian, nacalianism, nihobunka

Monday, May 01, 2017

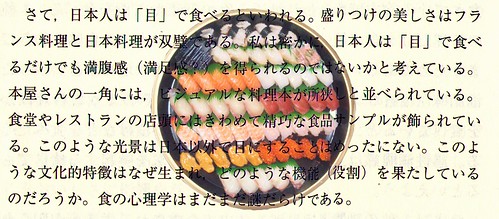

Eat with the Eyes

"Further, the Japanese are said to eat with their "eyes". The two pillars of beautiful food layout (moritsuke) are those of French and Japanese cuisine. I am privately of the opinion that the Japanese can sate their desire for food if not their appetite by eating with their eyes alone. There are shelves packed with highly visual cooking books in Japanese book stores. There are displays of highly detailed model food in windows of Japanese restaurants and canteens. This sort of phenomenon is rarely seen outside of Japan. How did this cultural peculiarity arise and what role does it serve? Their are still many riddles to be solved in the psychology of food." (Imada, 2005, p.58, my translation)

I could not agree more and believe this eating with the eyes to be a major reason for Japanese svelteness, that an the fact that in general the Japanese live with their eyes too.

Imada, S. 今田純雄. (2005). 食べることの心理学―食べる、食べない、好き、嫌い. 東京: 有斐閣.

Labels: japanese culture, nihobunka, 日本文化

Tuesday, September 13, 2016

Contextualism in Time and Space

Possibly the most interesting utterance for me at the recent IACCP conference in Nagoya was that by Yoshi Kashiima in his role as discussant on the presentations by Hazel Markus and Shinobu Kitayama. Professor Kashima expressed interest in the fact that while the Japanese self is contextual (felt to change and changes according to the geo-socio context) it is also time invariant. Wow. A penny dropped.

The Japanese members of the society, or at least those that live in Japan, are incredibly time invariant. The majority of these esteemed researchers appear to be and behave as if in a 'motionless present' (Geertz, ): they have not changed a bit. Consider Professors Shinobu KItayama, Minoru Karasawa, Masaki Yuki, Susumu Yamaguchi. Their appearance especially, and to a large extent their pluck (gennkisa) and even research interest is time invariant. Most seem even to have grown younger.

Western, or Western domiciled esteemed researchers, have on the other either changed in appearance or changed their research interest considerably. Professor Steven Heine is well kept, but does not dye his distinguished hair and has moved from self-enhancement, through the essence of culture, the WEIRDness of Westerners, to sleep. Professor Hazel Markus has moved from theoretical research on the independent self (possible selves), through the famed distinction, choice and now to the application of her student's theory.

The Japanese self is "imaginary" (Naclan, Takemoto), or "lococentric" (Lebra 2005) and as image is bound to its background (Masuda) so changes according to geo-social context. I knew this much before hearing Yoshi Kashima's comment.

But, thanks to Yoshi Kashima I now realise that, it is also true that the Western self as narrative is also contextual. It unfolds in time (Derrida, Heidegger, Bruner) and Westerners have great narratival plans for their lives (Sonoda), whereas Japanese hardly make future plans at all. Westerners are contextual in time!

It is not that Asians are more contextual, it is simply that the dimension in which the self unfolds is different. Japanese are contextual according to the spaces in which they appear, and invariant in the temporal media which is invisible, Westerners are contextual according to the time in their self narrative that they are enacting, but invariant in the un-narrated, and ignored (Masuda) background to their narrative.

These modal difference result in other qualitative differences of course. Japanese can, to a larger extent choose the context in which they exist. Westerners devise their plot-line, but march to the beat of time.

Labels: japanese culture, nihobunka, 日本文化

Friday, March 11, 2016

Climbing Authenticopies

Edo period Japanese were fond of visiting Ise Shrine, other shrines and temples, and also famous mountains, none more so than Mount Fuji. However the purpose of visiting Mount Fuji was not to enjoy the view from the top, which as the saying goes is preferred only by stupid bigheads and smoke (baka ya kemuri ha takai tokoro ga suki). So instead of climbing the mountain, they more often chose to climb a model of the mountain, wearing full pilgrim's attire, at one of the shrines at the base of Mount Fuji (Ohwada, 2009, p. 40: quote in Japanese below).

There is no size information in the visual. A bonsai tree looks the same as a massive oak, and a model of Mount Fuji can look the same as the real thing. If you wear the right kit and walk up a model, then you might as well have walked up the actual mountain, because they will look the same way. In he land of the sun-goddess the authenti-copies or simulacra (Baudrillard, 1995) are not words, which Westerners feel to be perfectly copyable because we have a listening comforter, but visual replications such as of mountains in front of Shinto shrines.

Japanese culture is rife with authenticopies such as bonsai, model food in place of menus, dolls, horse and cow sculptures at shrines, masks, pictures of the deceased and his royal highness the emperor, and the god-head (goshintai) of the deities themselves that can be copied or split 'as one can split a fire' (Norinaga, see Herbert, 2010, p.99). The practice of visiting copies continues to this day in the form of creating foreign villages ("gaikoku mura") which fascinate foreign anthropologists and tourism theorists (Graburn, Ertl, & Tierney, 2010; J. Hendry, 2000; Joy Hendry, 2012; Nenzi, 2008). I don't think that they have noticed that the Japanese world is inside out yet, however.

If it were indeed the case, as argued here, that the Japanese world is that of light, an amalgam of images, seen and 'insured' by the watchful eye of the Sun goddess, then in order for someone to pass from Western to Japanese culture, from a Western to Japanese world, they would need to pass through the veil of perception. Perhaps all one really needs to do is find the dead girl that you are talking off to.

Perhaps that is what David Lynch (1992) meant by "Walk fire with me".

The above image is composed of a detail from the model mountains (though not of Mount Fuji) or standing sand (tatesuna) in Kamowake-Kazushi Shrine precinct by 663highland, and image of a monk in a straw hat from gatag copyright free image source.

富士山の場合は、富士山に実際に登山していわゆる富士山禅定(ぜんじょう・登る=修行)を行う者はむしろ砂苦、大多数はしないの富士山神社や諸社寺境内に設けられた箱庭式で模擬登山を行うのであった(大和田, 2009, p. 40)

Bibliography

Baudrillard, J. (1995). Simulcra and Simulation. (S. F. Glaser, Trans.). Univ of Michigan Pr.

Graburn, N., Ertl, J., & Tierney, R. K. (2010). Multiculturalism in the New Japan: Crossing the Boundaries Within. Berghahn Books.

Hendry, J. (2000). Foreign Country Theme Parks: A New Theme or an Old Japanese Pattern? Social Science Japan Journal, 3(2), 207–220. http://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/3.2.207

Hendry, J. (2012). Understanding Japanese Society (4th ed.). Routledge.

Herbert, J. (2010). Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. Taylor & Francis.

Lynch, D. (1992). Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

Nenzi, L. N. D. (2008). Excursions in identity: travel and the intersection of place, gender, and status in Edo Japan. University of Hawaii Press.

大和田守. (2009). こんなに面白い江戸の旅. (歴史の謎を探る会, Ed.). 東京: 河出書房新社.

Labels: authenticopy, japanese culture, Nacalian, nihobunka, Shinto, tourism, 日本文化

Monday, February 29, 2016

62 Translations of Okonomi Yaki

Fritters as you like them. Fritters to taste. Free fritters. Fritters freed. Japanese pan fried pizza. Savory pancakes. DIY fry-up. Griddled Goo. Individualistic johnnycakes. Selfish savories. Preference, predilection, prepossession, propensity, personalised or pet pancakes or paste. Pet preparation. Wished or whimsy waffles. What you will waffles. (Free)Will waffles. Flavour Flapjacks. Groove griddle cakes. Number one gunge, My cup of tea cakes. Croquette my way. Darling, dearest, desired, or druthers doughboys or dumplings. Liberty cakes. The cook is on holiday cakes. Be my batter cakes. Beloved batter cakes, Coagulated stir fry. Callous cutlets. Choice cabbage cakes. Liking or Love lump cakes. Main mush. Choice Concoction. My mix. Pan fried partiality. Pan-fried perfection. Caprice cakes. Hobby hotplate. Free-style fries. Fried fantasy. Freedom fries. My fry. Favourite fries. Hashed heaven. Hashed happiness.

My students always 'translate' the name for Japanese foods such as that pictured above (お好み焼き) using their phonetization, "okonomi yaki," which might just as well be kowwash firdight for all the meaning it would impart to the average anglophone. This is I think because people hate meaninglessness (Heine, Proulx, & Vohs, 2006) so if at least one word in Japanese is included in any sentence the sender knows that at least that one word will be meaningful in a Japanese context, and that their conversation partner will have some idea of what they are talking about. The reasons for this is anatta or no self. The self is just a representation (story or image): something with a meaning. The lack of meaning is self-annihilation, and English conversation practice almost deadly. I need to be nicer to my students, investigate Japanese hospice praxis, while insisting that students use non-phonetic translations.

Heine, S. J., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 88-110.

www.google.co.jp/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&...

Addendum Good Paper on Japanese hospice praxis emphasises the use of image-based measure (PAC analysis) rather than scales. Recommends, in addition to palliative care and listen: smiles and improved personal hygiene and health on the part of the carer. I try to always attend conversation class wearing a business shirt and tie.

對馬明美, Tsushima, A., 三上佳澄, Mikami, K., 西沢義子, & Nishizawa, Y. (2010). 死を意識している患者との対話場面における看護者の態度構造に関する研究. 日本看護研究学会雑誌, 33(5), 33-44. http://www.jsnr.jp/test/search/docs/103305003.pdf

内藤哲雄1997/2002PAC 分析実施法入門[改訂版]「個」を科学する新技法への招待ナカニシヤ出版 amazon link a student gave a presentation about this. I thought it came from outside of Japan.

内藤哲雄. (1997). PAC 分析の適用範囲と実施法. 信州大学人文学部人文科学論集< 人間情報学科編>, 31, 51-87.

https://soar-ir.repo.nii.ac.jp/index.php?action=pages_view_main&active_action=repository_action_common_download&item_id=707&item_no=1&attribute_id=65&file_no=1&page_id=13&block_id=45

Labels: els, english, englishconversation, nacalianism, nihobunka, self, 日本文化

Monday, January 26, 2015

Look at this Figure Now!

"Look at this figure now!" the image above is one of many mother and child joint attention pictures from the floating world of ukiyoe artists which, according to the famed psychologist Osamu Kitayama, express something important about the Japanese mind. It shows a mother showing her rather terrified child a glove puppet.

Osamu Kitayama is right and further, I think that these express the cosmology of the Japanese.

If one has (or has modelled) a linguistic, listening father figure, "super-ego," or "generalised other" in ones mind then concepts or later "matter;" that dark stuff that has properties, can be thought to be the essence of things and the visuals, "res extensa" a fleeting subjective veneer.

But, if one shares ones heart with a vast and joint attentive seeing mother, then the figure, or face, can be the centre of gravity of the self, and of things also.

Words and their meanings are no less subjective. The deciding factor is the nature of ones generalised other: does s/he hear or see.

I don't think that there can be any deciding who is right about the cosmos, but it is interesting to note that scientists are now experimenting to see whether the universe is two dimensional a two dimensional floating world in which three dimensionality is an "emergent" property.

Labels: image, japan, japanese culture, nihobunka, 自己

Monday, July 30, 2012

Empire of the Circles

The mirror of the Sun-Goddess, which she carries, represents her, is her or her mind, is eaten to ingest her, contains (in the form or Enma's mirror) ones whole life, represents Japan as its flag, its families in their crests, themselves in their seals, is used in numerous postive expressions for completeness and the absense of imperfection, is found emphasised in the faces of infants characters, and is the meaning of the word "yen."

To express good Americans use a circlular sign in the form of an okay sign. The Japanese use this sign as well as that made by making a circle using their arms surrounding their head. They also sit in circles, give people circular cards for their signature and all the other things in the image above which I will explain with reference to Nishida's place, or mental mirror (Heisig) which Westerners may understand as the visual field (bottom right) but in fact it remains, as ones heart, even when ones eyes are closed.

Third Row Image Credits

Mori Ranmaru kamon by aikao

Japanese flag by wisegie, on Flickr

Hanko ~ Japanese Signature by Jason Michael, on Flickr

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihobunka, specular, 日本文化

Friday, July 13, 2012

Japanese Entrance Hall (Genkan) with Sofa

A genkan is a entrance hall, at a slightly lower level to the rest of the house which is raised, where people take off their shoes before entering the home. It is also used as a place to display ornaments and sometimes as a place to briefly entertain casual visitors. It is not uncommon for householders to kneel in the corridor just beyond their genkan, while their visitor stands on the lower genkan floor.

To make casual visitors feel more comfortable, this (very unusual) home in a Buddhist temple's grounds has a three piece suite in the genkan, so that the monk can entertain without allowing visitors into the home.

The home is considered more private in Japan and entrance to other people's homes is more often avoided. House parties are a rarity and generally limited to extended family members.

Entrance to another persons home, and the further one enters into that space, implies a greater degree of social intimacy. Nakane (1972) argues that Japanese groups, including the family, are considered to be bound together not by virtue of shared concepts such as common goals, or mutual love -- though of course they usually love each other -- but by their membership to, and ability to enter a shared frame, or place, such as the home. Family members refer to each other as "our place's bride' (uchi no yomesan) 'our place's granny," (uchi no obaasan), or "our place's leader" (uchi no danna) meaning husband or patriarch. Marriage ceremonies are said to take place between homes or houses in a way reminiscent of marriages between European aristocracy*. Entering a Japanese person's home, to its depths at least, implies that one is a member of the family (see Bachnik and Quinn, 1994). These customs are indicative of the way in which the home is considered to be a special, semi-sacred space centred around the household altars (kamidana and bustudan), and as such an important vector of social cohesion.

Notes

* see e.g. the marriage between the House of Burgundy and the House of La Marck

Bibliography

Bachnik, J. M., & Quinn, C. J. (Eds.). (1994). Situated Meaning: Inside and Outside in Japanese Self, Society, and Language. Princeton University Press.

Nakane, C. (1972). Japanese Society (1st pb ed.). University of California Press.

Labels: nihobunka, nihonbunka, 日本文化

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

Japanese Spaceless Space & Western Timeless Time

Additionally bottom left, it is well known that Japanese love to go and see the passing of time, autumn leaves, and spring cherry blossom, or fields were once great castles stood. This may very Buddhist, and profound of the Japanese but it is worth bearing in mind that not only do they pay attention to the "A series" of becoming, but also to "B series" objective points in time related to the seasons, and specific dates. Time is out there.

Westerners, on the other hand, like to emphasise the extensiveness and exteriority of space with geometrical patterns in gardens, white celings and bay windows in their rooms. Space is seen as extended, complete with the concepts, the symmetry and geometry, that keep it so.

Westerners like spatiousness, big rooms, big views, big spaces. But they are conflicted because at the same time they want to preserve the past in their rooms and in their cityscapes. Westerners like to present time as if it were stationary, as if the past is is in the here in now.

Space is the medium of the self as image and mental mirror (Heisig, Nishida). Time is the substrate of the self-narrative and language as thought (Derrida, Kim).

Addendum

The above is not right. And it is a make or break post.

Conventional wisdom has it that the Japanese are (Buddhist) relativists, and that Westerners are the objectivists that believe in the world and the world and themselves, due perhaps (though scientists would not agree) to their belief in a third person, an Other.

And I too thought/think that the Japanese fondness for scale trickery and their fondness for the changes in nature were both indications of a tendency towards anti-objectivity, and relativism.

But if that is the case, then my argument that the Japanese are like Westerners but in a different modality or channel, that they have a different kind of Other, a different kind of objectivity, would have to be rejected.

Because space is surely the plane, substrate, or place of the visual (self) and time is argued (by Derrida especially) to be the modality, medium, or (dare I say place? topos, axis?) of the phonetic narrative (self). Place is where vision takes place, time is where phonemes unfold. If so then attitudes towards space and place should exhibit a similar "Nacalian" reversals (if such exists) as between word and image. Attitudes to space and time would or should be related through a meta-Nacalian reversal.

I am having a problem seeing any such reversal. It still looks to me rather like Westerners are being objective, and Japanese are being relative, about both space and time but I hope not.

I was wrong to say that Japanese are into the B series of time. First of all, they use period names for dates rather than relating everything to a year dot. The period names encourage, I believe, a before after view of time rather than some objective temporo-cartesian coordinate (X years AD).

So okay, Westerners are into the year dot, the B series of time, whereas (other than Mecca and Jerusalem) there is little in the way in the West to speak of or identify a "B series of space". Our Western God is omnipresent. Japanese gods on the other hand have a "place dot," or many scared space that dot, anchor and objectify the space. On this basis it is Western, or at least Newtonian, space that is "indexical" (before me behind me) related to a inertial, three dimensional frame of reference.

But then this goes against

(1) Bachnik and Lebra's theories regarding the "indexical", relative nature of Japanese space perception, emphasising inside (uchi) and outside (soto), front (omote) and back (ura).

(2) The destruction of scale in Japanese plants (bonsai), gardens (zen gravel gardens), and interiors (if my observations regarding the tricks used to destroy perspective are correct).

Other observations

How should a comparison of Japanese and Western space and time perceptions be approached?

A) By considering the ways in which space and time perceptions inter-penetrate and dominate, arguing that the Japanese have a spatial view of time, and Westerners have a temporal view of space, perhaps.

Japanese time perceptions don't have the year dot but they have a sort of C-series, or rather C-loop, in that the fleeting nature of cherry blossom is not seen as solely a purely Heracleatean flux but as something that will repeat. Perhaps it could be argued that this cyclical view of time results in a the creation of a "time-space." the seasons of the year. Do Westerners have a temporal view of space? Does the geometry and regularity of Western gardens and architecture reflect the tick tock of a clock?

B) From the point of view of a conceptual abstraction capable of framing both time and space. E.g. by abstracting the "A series" and "B series" to apply to space as well as time? Or the use of words such as "flow" and "repetition," and "reference point" that may perhaps be applied to time and space?

The geometric gardens and Neo-georgian cityscapes emphasise the "flow of space" as cherry blossom emphasise the flow of time? Geometric gardens and cherry blossom may also emphasise a repetition. And finally, perhaps in both geometrical gardens and cherry blossom there is an absence of a spatial or temporal reference point respectively. How?

Do antiques present any sort of "trick" corresponding to the scale destroying 'trick' of gravel gardens, bonsai trees and Japanese interiors? Does "Neo-Classical" Georgian architecture of Bath present a similar sort of dillema: instead of an unanswerable "is this big or small", "is this old or new."? Does neoclassical architecture, or do shiny polished antiques forces their viewers to suspend judgements of time? Is there a British Zen!? I have never felt that Bath architecture was in any way Zen when I lived there but perhaps to a Japanese visitor it presents a similar "vortex" of conflicting, interpretation defying, agelessness.

If so this would help me to understand Japanese architecture. Japanese architecture confuses me, creates in me a vortex of trickery, but I am sure that Japanese that are used to it have suspended judgement already. To them it is peaceful, as Bath architecture was to me. Perhaps when I lived in Bath I had already suspended judgement as to whether buildings are old or new. Bath architecture was old AND new, as bonsai trees and gravel gardens and big and small.

If bonsai trees and Bath architecture are both a trick then, both should leave a pure experience of something. I can grasp, however fleetingly, the way in which Japanese architecture makes me "see the light," "the purity of experience" through "cessation" of interpretation. But what does Western architecture make anyone see (or hear?). Am I too anti-Western, anti-temporal. "Cessation" sounds profound, but is a very anti-temporal term. Perhaps "purity" is also linked with space. It is certainly linked with Shinto.

When Husserl and Nishida engage in 'bracketing' they experience different things. Nishida stopped (with all the anti-temporality that that implies) interpreting and saw the place/space/mirror. Husserl on the other hand discovered (with an implied anti visio-spatialness) the transcendent the "irreel," "forms". I have always been dismissive of the latter, dismissed Plato's spelunking satori as mere myth. The forms are fantasy, mere words, I thought. Or again I may have been too keen on vision. When Nishida or Zeami experience their place or flower, they might be the first to admit that there is nothing to see.

I need to change my title, which is now, "Japanese Space Unextended & Western Time That Does not Flow." Japanese space is still in some sense extended (how can space not be) but scale, big small, this in front of that distinctions are lacking. Western time, or at least the antiques, are old but here still, past but present. They both (Japanese space and Western time) lack something, and have something gained. Space-less Space and Timeless Time? I will go for that.

Anyway, am I an old structuralist dog chasing something or just a waffler?

More (thanks to Ms. Hajima)

Ryoutaro Shiba and Donald Keene point to similar differences but reach opposite conclusions in their discussion of the Japanese and Japanese Culture. They say that Europeans do not want to feel time (then why the obsession with antiques, even with rows of things evolving over time even), and are pleased if works are preserved completely as if it were made the day before. This is true, and great labour goes into preserving antiques I know as the son of a picture restorer. But at the same time, it is important that the antique is old. It is important to Europeans that an item looks both new and also it is important that it be old. In Japan however, very little importance appears to be given to preserving old things, or to age itself, with Ise Shrine and Japanese houses being rebuilt regularly. Donald Keene and Shiba also claim that Japanese prefer works that are broken a little or faded.

Top Left: Joueiji Temple Zen Gravel Garden by me

Top Right: Ham House Garden by neilalderney123

Middle Left Japanese house traditional style interior design / 和室(わしつ)の内装(ないそう) by TANAKA Juuyoh (田中十洋)

Middle Right: "Prospect Park Place West Victorian brownstone interior dining room fireplace mantle by techpro12. Techpro12's blog has many similar images.

Bottom Left: 紅葉 (red leaves)by jasohill

Bottom Right: Bath Crescent HDR by alex_smith1

Labels: Nacalian, nihobunka, nihonbunka, 日本文化

Friday, July 06, 2012

Cosplay Mimics the Visual Visually, Impersonation Mimics the Voice Vocally

Cosplay refers to wearing a COStume to play or mimic a cartoon (anime) or comic (manga) character. It is particularly popular in Japan where there are large events held periodically where costumed people like the lady above, get together. Cosplayers can also be seen in the Harajuku area of Tokyo, and all over Asia, and now the world, since Cosplay has spread out from Japan. In Japan it is far from being a widespread phenomena. It is the sort of thing that like dancing, the Japanese would not want to do badly. Cosplayers will go to considerable lengths to get their clothes, hair, make up and poses just right.

Cosplay is doubly visual. Firstly, cosplayers rarely speak but rather just pose, often for photographs. Their mimicry is a visual art. Secondly the object of their mimicry - the cartoon and comic characters - are particularly visual existences. I will argue that Japanese comics are more visual, hyper-visual when compared with Western cartoons and graphic novels in another post but here I want to suggest that cosplay is the predominantly visual mimicry of the predominantly visual.

These Japanese cosplayers are strange eh? I can feel "conformist," tripping off readers' lips, because isn't copying always conformism? Yes, copying is always to an excent conformism but please see the last paragraph. And futher, the Japanese are not, Asians are not, particularly conformist. Does this lady look conformist to you? Doesn't she look weird? She may still look conformist because she is not speaking. Without speech it may seem as if she has less personality than an endless loop tape recorder (see previous post) but, that is because Westerners are logocentrist.

Performing a Nacalian transformation, the Japanese Cosplayer in the imaginary is equivalent to the Western voice player, more commonly refered to as the impersonator*.

Back when I lived in the UK I used to mimic vocally a purerly vocal existence: "Mr. Angry" of the "Steve Wright in the afternoon" radio show. I was the UK equivalent of a Japanese Cosplayer. I was as conformist, but probably not as good. I would not have done it had I thought my mimicry would not be recognised however. My voice (like the appearance of the Japanese) is not something that one plays with lightly.

It seems to me that Western impersonators are Nacalianly transformed Cosplayers because they predominantly vocally mimic predominantly vocal existences. This is not to argue that Japanese cosplayers say nothing at all, or the Western impersonators do not change their appearance at all, but there is a strong difference in emphasis. The personality or self that is mimicked and does the mimicking is felt to reside in the face and appearance in Japan, and the words and voice in the West.

Please have a look at some impersonators on Youtube. You will see that not only do they change their appearance very little, but also that they choose particularly characteristic voices to impersonate. For that reason, Christopher Walken, and Al Pachino are comon favourites. Cosplayers choose characters that are easily visually recognisable such as Hatsune Mikku above. While the days of radio - such as the Goon show - are gone, and all characters these days have visual and verbal aspects, the characters that are impersonated in the West are defined, as Westerners are defined, above all by our words and voice.

Here are some Western

Finally it should be noted that to a degree Westeners are all impersonations, and the Japanese are all cosplayers, because the self is nothibng more or less than self mimicry, there is not self, no individual other than in this attempt at duplication. The self is created through an attempt to visualise oneself, or narrativally impersonate oneself into existance.

This post was inspired by a kind question from Mudakun.

Notes

*There are also impersonators in Japan, just as their are fancy dress parties in the UK but I argue that Japanese impersonation (monomane) even or especially rakugo, is extremely visio-imaginary. Please see this introduction to rakugo in English.

Labels: authenticopy, collectivism, individualism, Jaques Lacan, mime, mirror, Nacalian, nihobunka, nihonbunka, reversal, specular, 日本文化

Thursday, July 05, 2012

Fundamental Attribution Error, Nakajima, and Endless Loop Tapes

Professor Nakajima is a recently retired professor of Kantian philosophy. He is, I believe, highly Westernised. He spent a considerable amount of time in Germany, presumably speaks German, and studies and presumably loves one of the most Western of philosophers: Kant.

It takes leaving ones culture to know it. Normally ones own culture is so obviously-the-normal-way-of-doing-things that it is transparent. It is only those that have participated in other cultures that can see there own. Professor Nakajima was sufficiently deculturized to realise that public announcements of various sorts in Japan are strange.

Japan is awash with public announcements in the form of recorded or electronically simulated voices that blare out messages such as vending machines or cash dispensers that greet their customers, buses that announce that they are reversing, election trucks that blare out linguistically meaningless recordings of a politician thanking people for their support, and endless loop tape recorders that blare out the special offers in retail outlets as pictured in this photo. The endless loop tape recorder shown here stood at the entrance to a local electronics store endlessly shouting out the special offers on sale at the store.

In the first few years of living in Japan I used to stop in front of these endless loop tape recorders and attempt to understand what they were saying. One of the reasons that I did so was because my Japanese language ability was insufficient. But even when I was able to understand the language of the tape, I still stopped, and listened while Japanese store goers walked on by, seemingly oblivious. I found the endless loop tape recorder arresting, more worthy of attention, and very strange.

When I first arrived I arrived in Narita airport in Tokyo, I got on a horizontal escalator / conveyor belt walkway (what are they called?) and shortly before the walkway came to an end a voice came out at foot level warning me that the walkway would end. I picked up my feet as if I might step on the unseen announcer that must (I felt) be hiding underneath the moving hand rail. Shortly thereafter, when I first purchased a canned drink from a vending machine in Japan that spoke, I felt that there was a woman (in Japan it is generally a woman's voice) hiding inside the vending machine thanking me for my custom.

I am now used to all the depersonalised voices that one hears in Japan. It no longer surprises me when buses 'say' "reversing, reversing, reversing." It no longer surprises me when bullet trains 'say' "Please don't bring dangerous things onto this train."

Nakajima (brilliant though his observations are) explains this phenomenon -- the tendency for there to be disembodied voices in Japan and their strangeness -- using the same old same old collectivism vs individualism trope. He points out that private speech, such as by students in class, or by people using cell phones on trains (I am not sure if he used these examples) is repressed, not-allowed-in-Japan, and argues that speech is only allowed when it is a public, disembodied, announcement.

[He does not note for instance that Western city-scapes are required to be uniform by planning permission rules or that Japanese fashion is the zaniest in the world]

Nakajima also complains (if this is the right word) of the loudness of these announcements which prevent private speech, or western style (Kim, 2002) "thought".

It seems to me that my issue with these endless tape recorders, and other linguistic public announcements is rather directly associated with the Fundamental Attribution Error.

The Fundamental Attribution Error refers to the tendency of people to assume that behaviours are the result of traits.

According to this theory, we, humans, have an erroneous tendency to believe for instance that if a person is late to a meeting then that is because that person is not a punctual individual.

Most of the research on the fundamental attribution error, however, concentrates on one behaviour: reading out loud from texts that are constrained. When Westerners listen to someone read out loud, then even if they know that the text that the person they are listening to is reading a text which that person has been forced to read, Westerners still believe that the person in question believes in the purport of the text. The text as read out loud is felt to be expressive of the mind, person, self, of the individual.

Japanese people however are far less likely to feel that a reading out loud represents the true feelings of the person that is doing the reading.

This difference is ascribed to the purported fact that Japanese are, and realise themselves to be, less individual, more collectivist, more context dependent. When a Japanese person hears someone reading a text then they do not assume that the text represents that person, merely that the person is (as is the case under constrained conditions) merely conforming to pressure, because social pressure is rife in Japan, and free self expression is not allowed in Japan.

This, the conventional interpretation is hogwash (false). The Japanese are as free to express themselves as anyone else, or more so. But the medium or mode of their self expression is Nacalianly different. That the Japanese can create cityscapes, products, images, fashion in such zany abandon testifies to this fact.

The reason that Westerners (and Westernised Japanese) find mechanically produced, or constrained speech to be representative of traits is because that we Westerners believe that we are speech, that thinking is speech, that the person is speech. The Western self is a narrative. The strangeness of these endless tapes that announce products, and other announcements produced by machines, are the same as the reading-out-loud used in Fundamental (!) Attribution Error research, and their potency can be explained in the same way.

Westerners believe that they are themselves narrations, speeches. Speech is thought. Speech is felt to be accompanied by (chimerical) ideas. Speech is felt to be the product of, the essence of a person.

And so, Westerner that I am, when I heard those mechanical/recorded/computerised voices in Japan, I presumed them to be, or desired them to be, from a person. Japanese public announcements expose the lie of my being: speech does not imply an existence, nor is it necessarily accompanied by an existence. Speech is just speech. There are no "ideas." Speech is noise. With regard to speech (but not to self-representational images) Japanese people realise this.

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japan, japanese culture, Jaques Lacan, nihobunka, nihonbunka, reversal, self, specular, 日本文化

Wednesday, July 04, 2012

Surnatural Tree Pruning

Surnatural Tree Pruning a video by timtak on Flickr.

The above animation used an original photo "isolated branches," with kind permission by ecormany.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nature, nihobunka, 日本文化

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Japanese Interiors: Japanese Art and Artifice

Through the use of a lot of rectangular spaces, such as the rice mats (tatami), and the squares in the sliding doors (shouji), traditional Japanese interiors at once emphasise perspective and depth but at the same time, due to the fact that these rectangles are of difference sizes, and additionally due to the inclusion of gaps in walls (ranma) and partitions, one is never sure whether one is seeing depth (through a gap for instance) or seeing something miniaturised.

(See for example the area of in the outer corridor see through the window in the wall, highlighted with a note on the photo page).

Hence Japanese interiors encourage their viewers to make incorrect spatial interpretation and so confuse - like walking into an Escher - that their viewers cease spatial interpretation altogether. This cessation leads us to see the interior as the primal space (Mochizuki, 2006), visual field (Mach, 1894), or mental mirror (Heisig, 2004) that is the purity of its experience (Nishida, 1979).

Japanese gardens also produce a similar Zen experience by confounding the viewers sense of scale, not using by using perspective lines and rectangles, but by using rocks and gravel that can and are interpreted as islands or an ocean respectively.

Japanese poetry – particularly haiku – achieves the same effect by encouraging the viewer to make an interpretation before returning them to the purity of the experience shared with the poet. E.g. most famously in Basho's poem: “An old lake” (we imagine it), “Frogs jump in” (we imagine them), “The sound of the water” (wham!), we are told that the poet did not see any frogs, perhaps not even the ripples; the sound of the water was all there ever was: "frogs jump in" was only an interpretation. Pound (1914) recognises that Japanese poetry layers images in a "vortex" but he does not mention that both"hokku" example he cites, and even, though Pound may not have realised it, the poem he wrote himself ("In the Station of a Metro", see the paper online, p4), contain a misinterpretation in the vortex of images.

In all three cases (interiors, gardens, poems) the artist encourages the viewer or reader to make a interpretation, or draw to mind an image, that is not based in the pure experience, and by confounding it, leads the viewer back to the purity of experience, to the 'ecstatic' ‘thou art that’ (Lacan, 2002)

Afterword

Does Japanese architecture, gardening and poetry lead to a sort of enlightenment? I think that it may at once be a sort of enlightenment, and at the same time furthest from it. The experience of traditional Japanese house interiors for Japanese returns their consciousness to that state of transcendental meditation which corresponds to (and is directly opposite from) Husserl's phenomenological state (Husserl, 1960) in which Western consciousness removes itself from phenomena and attends only to an interior narrative. Husserl's transcendental meditation is a return to the self, to the purity of self narrative, to that "Ravine" (Ace Of Base, 1995) where there is only self and 'Other', or 'super-addressee'. The Japanese architectural interior likewise returns the Japanese mind to the purity of the mental mirror (Heisig, 2004) ’where to abide with their creator god’ (see Claire, 1986), the looking together (Kitayama, 2005), eye-in-the-sky (see Masuda, Wang, Ito, & Senzaki, 2012; Cohen & Gunz, 2002; Takemoto, T., 2002).

Bibliography

Ace Of Base. (1995). Ravine. Retrieved from www.youtube.com/watch?v=dgBBFlvRdRc&feature=youtube_g...

Clare, J., Williams, M., & Williams, R. (1986). John Clare: selected poetry and prose. Routledge. Retrieved from books.google.co.jp/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Hebg8BrvCP4...

Cohen, D., & Gunz, A. (2002). As seen by the other...: perspectives on the self in the memories and emotional perceptions of Easterners and Westerners. Psychological Science, 13(1), 55–59. Retrieved from web.missouri.edu/~ajgbp7/personal/Cohen_Gunz_2002.pdf

Heisig, J. W. (2004). Nishida’s medieval bent. Japanese journal of religious studies, 55–72. Retrieved from nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/staff/jheisig/pdf/Nishida%20Medieval%...

Husserl, E. (1960). Cartesian meditations: An introduction to phenomenology. Translated by Dorion Cairns. M. Nijhoff.

Kitayama, O. 北山修. (2005). 共視論. 講談社.

Lacan, J. (2002). The mirror stage as formative of the function of the I as revealed in psychoanalytic experience. In B. Fink (Trans.), Ecrits (pp. 75–81). WW Norton & Company.

Mach, E. (1897). Contributions to the Analysis of the Sensations. (C. M. Williams, Trans.). The Open court publishing company. Retrieved from www.archive.org/details/contributionsto00machgoog

Masuda, T., Wang, H., Ito, K., & Senzaki, S. (2012). Culture and the Mind: Implications for Art, Design, and Advertisement. Handbook of Research on International Advertising, 109.

Mochizuki, T. (2006). Climate and Ethics: Ethical Implications of Watsuji Tetsuro’s Concepts:‘ Climate’ and‘ Climaticity’. Philosophia Osaka, 1, 43–55. Retrieved from ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/metadb/up/LIBPHILOO/po_01_043.pdf

Nishida, K. 西田幾多郎. (1979). 善の研究 (Vol. 33). 岩波書店.Nishida, K. 西田幾多郎. (1979). 善の研究 (Vol. 33). 岩波書店.

Pound, E. (1914). Vorticism. Fortnightly Review, 1, 461. Retrieved from matthuculak.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/POUND%20Vortic...

Takemoto, T. (2002). 鏡の前の日本人. ニッポンは面白いか (講談社選書メチエ. 講談社.

Labels: image, japan, japanese culture, Jaques Lacan, lacan, nihobunka, nihonbunka, reversal, self, specular, 日本文化

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Points and Places, and Lines and Concepts

Westerners name the streets or lines on maps give the doors on the streets numbers, but do not name the points nor plots of Land. Japanese name the spaces and places but rarely name the lines on the map, giving only a few of the roads numbers.

Points and places are given numbers, secondary to named lines in the West, lines are given numbers in Japan secondary to points and areas in space.

Attempting to summarize....

Japanese society is organized according to spaces

1) There are many geo-climatic theories that are thought to explain Japanese behavior

2) Japanese groups are organized according to spaces and those that are members of those spaces.

3) Shrines are the geo-locational model for the home and other spatial groups.

4) Lines are probably not felt to exist.

5) If there are signs on lines (streets/ boundaries between floors) then it is not to name the non-existent line or boundary but to refer to the surrounding spaces. Sometimes these signs are indexical (in the case of floor signs) and sometimes they are iconic (in the case of plot maps banchizu). Japan is no more "indexical" than it is iconic. The biggest difference is perhaps in whether the sign is thought to signify something visual (space, the place), or something conceptual. Western signs are thought to represent concepts. Japanese and Chinese signs are thought to represent things, and places that one can see (Hansen).

In Western society, space is thought to be empty. It is not used as an organization tool or structuring function, but needs to be organized by named lines. Space exists, is cognizable in so far as it is bounded by lines, and given coordinates, or a street number. The lines are themselves named. The lines are the ideas represented by the names, rather than spatial entities.

Labels: japanese culture, nature, nihobunka, nihonbunka, 日本文化

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

The Dark Side of Japanese Recycling: The Lack of Reuse

Japanese recycling is thorough. We have to separate our garbage into several types: cans, bottles, plastic, paper, burnable, poisonous, large etc.

But when someone throws away a bicycle, it is against the law to take that bicycle from the garbage dump and ride it away and keep it. The bicycles are not reused, but recycled into steel.

The Japanese are avid recyclers. Reuse is very much more environmentally friendly than recycling the raw materials but the Japanese are not nearly so keen on reuse. I can think of two reasons for this.

Japanese people have a bit of a phobia about second-hand. Things are seen as becoming imbued with some psychological or spiritual aspect of their own, and of their owner. This Shinto related, animistic phobia is dwindling and the use of second hand things is becoming more popular.

Secondly the Japanese have a tendency to see the world as being made up of material rather than items. When Japanese look at things, from bicycles to pieces of plumbing (which of these are identical to you?), they see the material rather than the item itself. They are influenced in part by the Japanese language (M. Imai & Masuda, in press; M. Imai & Mazuka, 2007; Mutsumi Imai & Gentner, 1997; Mutsumi Imai, Gentner, & Uchida, 1994) in which nouns are almost all akin to English uncountable nouns, like "sugar," "flour," and "water," that is to say designating materials.

But still the powers that be in my university consider it expedient to recycle rather than reuse not only bicycles but vast quantities of reusable rubbish

Bibliography

Imai, M., & Masuda, T. in press). The Role of Language and Culture in Universality and Diversity of Human Concepts. Retrieved from www.ualberta.ca/~tmasuda/ImaMasudaAdvancesCulturePsycholo...

Imai, M., & Mazuka, R. (2007). Language-Relative Construal of Individuation Constrained by Universal Ontology: Revisiting Language Universals and Linguistic Relativity. Cognitive science, 31(3), 385–413.

Imai, Mutsumi, & Gentner, D. (1997). A cross-linguistic study of early word meaning: universal ontology and linguistic influence. Cognition, 62(2), 169–200. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(96)00784-6

Imai, Mutsumi, Gentner, D., & Uchida, N. (1994). Children’s theories of word meaning: The role of shape similarity in early acquisition. Cognitive Development, 9(1), 45–75. doi:10.1016/0885-2014(94)90019-1

Labels: nihobunka, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, Shinto, 日本文化, 神道

Japanese Tea Flavoured Ice Cream

A set of model plastic Japanese ice cream in buckwheat (soba) and green tea (maccha) flavours. Japanese like to see the food their are ordering before ordering it. The brown things stuck into the ice cream are not chocolate flake but traditional Japanese biscuits.

That the Japanese eat buckwheat and green tea flavoured ice-cream is less surprising than the fact that they are so good at copying things. I take the liberty of writing about Japanese "authenticopies" again since the above is my most popular photograph.

The culture of copying things in Japan is sufficiently widespread and revered as to have received academic attention (Cox, 2007). The Japanese copy everything from mirrors, horses, and cars, to foreign villages and especially food. While no one will attempt to eat these plastic ice cream cornets, they are seen as being delicious: sufficiently identical to the real thing as to arouse desire. Copies of things are given as offerings to Japanese deities at shrines where they are seen as sufficiently identical to sate desire.

I think that the practice can be understood by reference to the way in which Westerners believe in the copying power of the sign (Derrida, 2011). Words are thought to create a copy in the mind of their recipients of the meaning of the their sender. I have an idea and translate it into the "signified" the word "sender" for instance, and you read it and recreate an identical copy of the idea that I had in my mind. If I did not believe in this identical copies - these words that arise in my mind and yours - then I would be faced with an identity crisis since one of the ideas, the one corresponding to the phoneme "I" spoken to myself, is myself (Benveniste, 1971).

But how is it that you, dear reader, can understand my words in the same way as I do? The ability for humans to believe in the transference of meaning in this way, for meanings to be objective is due to their belief in God, or a simulation of the same. Gods too can be simulated (Baudrillard, 1995). Words "exist in", or are pegged to their understanding - a sort of gold standard - in the mind of an intra-psychic third party: someone that is always listening. As we speak to real others, we believe that we also speak to an impartial spectator (Adam Smith, 1812), a generalised other (Mead, 1967), an Other (Lacan, 2007), superego (Freud, 1913) or superaddressee (Bakhtin, 1986): all these are either words for a sort of imaginary friend or a deity (see Marková, 2006, for a downloadable review). By this device, since words are always public, as well as being in our heads we believe in their identical copy-ability.

In Japan the gods look rather than listen. The visual world is always shared. The visual world in Japan, which relegated to the nether land, a "mere image" or "veil" in the West, has the same properties as the Western sign: it is both in the world and in the head. The world and mind meet at the plane of the mirror that is seen with Japanese deities, especially the sun-goddess, who is that mirror itself.

We think nothing of copying signs. The Japanese think nothing of copying food.

Bibliography

Baudrillard, J. (1995). Simulcra and Simulation. (S. F. Glaser, Trans.). Univ of Michigan Pr.

Benveniste, E. (1971). Problems in General Linguistics. (M. E. Meek, Trans.) (Vol. 3). University of Miami Press Coral Gables, FL.

Cox, R. (2007). The Culture of Copying in Japan: Critical and Historical Perspectives. Routledge.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. (V. W. McGee, Trans.) (Second Printing.). University of Texas Press.

Freud, S. (1913). Totem and taboo. (A. A. Brill, Trans.). New York: Moffat, Yard and Company. Retrieved from en.wikisource.org/wiki/Totem_and_Taboo

Lacan, J. (2007). Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English. (B. Fink, Trans.) (1st ed.). W W Norton & Co Inc.

Marková, I. (2006). On the inner alter in dialogue. International Journal for Dialogical Science, 1(1), 125–147.

Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist (Vol. 1). The University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J. (2011). Voice and Phenomenon: Introduction to the Problem of the Sign in Husserl’s Phenomenology. Northwestern Univ Pr.

Labels: autoscopy, culture, eye, japan, japanese culture, mirror, nihobunka, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, self, Shinto, specular, 日本文化, 神道

Omou, the Japanese Word for Think, is Predominately Visual

The Japanese words for "think" (omou) and thought (omoi) are represented above in mixed logographic and phonetic script. The question as to whether Japanese and Chinese script does in fact transmit meaning directly from the visual "graph" is hotly debated (Hansen, 1993).

I strongly agree with Hansen. Characters do mean. Like Derrida's word "differance," (Derrida, 1998), designed I think to draw attention to the trace, or graph, there is a gap between the sound and the meaning in Japanese words. Derrida's word "differance" (to defer) is pronounced the same as difference (to be not the same), but means something else, as a graphic neologism on the page. Japanese words can mean different things depending upon the graph used, such as foot 足 and leg 脚, both pronounced "ashi,". Japanese is even more obviously logographic than Chinese, because in Japanese each characters can be pronounced many ways. For this and other reasons, even native speakers may be able to read the meaning of a character without being able to pronounce it. .

What is not debatable in my mind is that the act of thinking in Japan is extremely or predominantly visual. The Japanese words for thought shown above, as those in English, describe the calling to mind of both language and vision. However in Japanese one can think someone, e.g. "think her" (kanojo wo omou taking a direct object) and this means at least to call an image of her to ones mind. In so many other compounds of the Japanese word to think, such as "omoi-ukaberu" (float a thought), "omoi wo haseru"(direct ones thoughts) it seems clear to me that this act entails predominately the calling to mind of images.

Western thought as everyone since Plato tell us, is predominantly "the soul's discourse with itself" (Miller, 1981, see Kim, 2002).

Derrida, J. (1998). Of Grammatology. (G. C. Spivak, Trans.). JHU Press.

Hansen, C. (1993). Chinese Ideographs and Western Ideas. The Journal of Asian Studies, 52(02), 373–399. doi:10.2307/2059652

Kim, H. S. (2002). We talk, therefore we think? A cultural analysis of the effect of talking on thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 828.

Labels: image, japan, japanese culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, 日本文化

Talisman/Omamori/Good Luck Charm

The following is my explanation of the philosophy behind the good luck charms, or "Omamori" received from shrines and temples in Japan.

In Japan the lucky charms called "Omamori," (literally "venerated protectors") are said to work by being a decoy-self ("migawari) that attracts bad luck.

Hence any "impurity" or bad luck is collected in the charm instead of in the person. The charm is thrown away once a year, together with the bad luck.

There is quite a lot of theory behind this.

Omamori are basically very similar to the larger tablets bearing the name of the deity "ofuda" that one receives from a Shinto shrine. Both are termed "Shinpu" or deity tablets. These larger tablets are enshrined within the home on the Spirit Shelf (Kamidana). Omamori are also basically pieces of paper stamped with the name of the god.

Why should a piece of paper stamped with the name of the god be a decoy-self?

The easiest way to answer this question is by referring to Japanese "Buddhism". Japanese Buddhism concentrates on rituals for the dead. The dead are enshrined in the household inside a "Buddhist" altar or "butsudan" or (literally Buddha cupboard). Inside the Buddha cupboard there is an effigy of the Buddha, but perhaps more importantly there are a lot of little tablets (called ihai) which represent dead relatives. People open the butsudan and say "hello grandpa, hello grandma" to their grandfather, and grandmother (if deceased) in the form of their little tablets.

According to the Japanese ethnologist Yanagita Kunio, the Budda cupboard (Butsudan) and the Spirit Shelf (Kamidana) originate in the same practice. The spirit shelf was for the living and the "Bhuddist altar" was for the dead but basically in both there was a deity (Shinto Kami or spirit, or Buddhist Buddha) and in both there was representations of members of the household, living or dead. Before the introduction of Buddhism, people would receive spirit containing tags or earlier still branches and stones from their shrine. These would be periodically renewed, and eventually returned to the shrine after the death of its holder. With the separation of Shinto and Buddhism this cycle of spirit has been obscured.

Today in Japan there are few personal tablets for the living (other than omamori) but there are traditions of sticking the names of the living onto the shrine shelf in some parts of Japan. In the past, people received a part of the spirit of their local shrine and this in a sense gave them life. In other words a ticket or tag from the shrine represented a person, it was or is, another me.

This is why perhaps a "omamori" is a bit like a spare ID card. If you have some bad luck, like being caught doing a minor misdemeanour's then you charge it, or put it down to the spare ID, which you throw away at the end of the year.

The new year is said to be a rebirth, everyone gets a new identity. Everyone starts afresh with a clean slate.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, Shinto, 日本文化, 神道

Monday, June 18, 2012

"If you want to live a long time: Look in the Mirror"

The Japanese nation as a whole are one of the healthiest on the planet, with the highest life expentancy in the world (Wikipedia, 2012). Is it the burdock tea?

I think that Dr. Nagumo provides the answer in this latest book, entitled "If you want to live a long time: Look in the mirror." As argued repeatedly on this blog (see Heine, Takemoto, Moskalenko, Lasaleta, & Henrich, 2008) the Japanese are as if always in front of a mirror since they simulate an autoscopic view of themselves. Humans in general have this capability to see themselves from the outside in (Blanke & Metzinger, 2009). Somehow Westerners manage to forget how they look, which is why in some states of the US, one in three are obese (Witters, 2011).

In recommending autoscopy (looking at yourself) and burdock tea, Dr. Nagumo is recommening a Japanese way of keeping healthy to the Japanese. Someone should translate Dr. Nagumo's book into English. Additionally someone might also write a book in Japanese recommending Anglophone health-ways to the Japanese. Despite the fact that the Japanese look 20 years younger than Americans, they only live 4 years longer (82 vs 78: Wikipedia, 2010).

How can this be? The Japanese have a strong tendency to health ignore information that they can not see in the mirror, which is why approximately twice as many Japanese than Americans smoke cigarettes. My health advice to the Japanese woudl be to either (1) read health statistics and believe them, or better (2) think of ways of making invisible health risks visible, e.g. by the use of pulmonary endoscopy to take and show photographs of Japanese smokers blackend lungs to their owners. That would encourage them to quit smoking.

Bibliography

Blanke, O., & Metzinger, T. (2009). Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(1), 7–13. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.10.003

Heine, S. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 879–887. Retrieved from www2.psych.ubc.ca/~henrich/Website/Papers/Mirrors-pspb4%5...

Wikipedia contributors. (2012). List of countries by life expectancy. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_countries_by_l...

Nagumo, Y. 南雲吉則. (2009). 錆びない生き方. PHP研究所.

Nagumo, Y. 南雲吉則. (2012). 長生きしたい人は「鏡」を見なさい. 朝日新聞出版.

Nagumo, Y. 南雲吉則. (2012). 20歳若く見えるために私が実践している100の習慣. 中経出版.

Witters, D. (2011). One in Three Adults Obese in America’s Most Obese States. In A. Gallup (Ed.), The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion 2010 (pp. 262 263). Rowman & Littlefield. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/141734/one-three-adults-obese-america-three-obese-states.aspx

Labels: japan, japanese culture, mirror, nihobunka, occularcentrism, 日本文化

Language and Gesture Revisited

Professor Kita's research does not lie well with the general "Naclanian" theory promoted by this blog: that the Japanaese are imago-centric. If they were, one would expect them to gesture the movements of objects as those objects appear, rather than be influenced by their language.

It is important to remember, however, that: while these gestures were made while speaking the majority of Japanese speakers (e.g. almost two thirds in the swing experiment) were indeed unaffected by their lack of a verb to swing, and that both of Professor Sota's experiments used movements for which the Japanese lacks a suitable movement verb, which is present in English.

What would happen in the reverse situation, where English lacks an appropriate movement verb? The animation above shows one such situation. In English the verb usually used for downwards motion under the effect of gravity, whether straight down or to the side, is "fall down". Japanese distinguishes these verbs, where "ochiru" is to fall straight down, and "taoreru" is to fall down sidewise like the man in the above animation (right click for menu to replay, or refresh screen).

I hypothesise that more than one third of English speakers would gesture these two events in the same way (if they were not shown side by side), since English speakers are even more influenced by the impact of their language (as was also indicated in Professor Sota's research, 2009).

As an aside, I also predict, in line with the Sapir-Worph hypothesis and recent research (Boroditski, 2001; Imai and Masuda, in Press) and others that that English speakers would see more similarity in the the movement of the bottle and the man that Japanese speakers.

Bibliography

Kita, S. (2009). Cross-cultural variation of speech-accompanying gesture: A review. Language and Cognitive Processes, 24(2), 145–167. doi:10.1080/01690960802586188 Imai, M., & Masuda, T. (in Press). The Role of Language and Culture in Universality and Diversity of Human Concepts. Retrieved from http://www.ualberta.ca/~tmasuda/ImaMasudaAdvancesCulturePsychology2012FINAL.pdf Boroditsky, L. (2001). Does language shape thought?: Mandarin and English speakers’ conceptions of time. Cognitive psychology, 43(1), 1–22.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, 日本文化

This blog represents the opinions of the author, Timothy Takemoto, and not the opinions of his employer.