Wednesday, January 27, 2021

Only in the Eyes of God, and Themselves

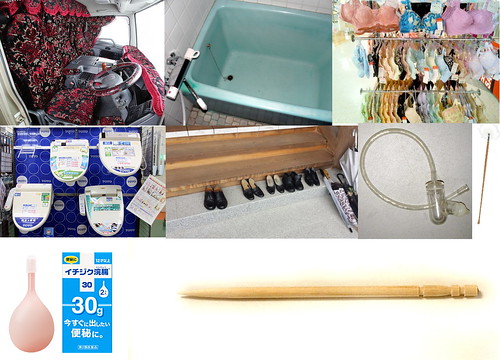

The Japanese are said to be hygienic because they care about how they look to others but many Japanese hygiene and prettifying behaviors such as, decorating the interiors of their cars and trucks, bathing at night, wearing fancy underwear (that sometimes becomes outer wear it is so fancy), bidets, not wearing shoes at home, snot suckers, enemas, the popularity of ear cleaning, the prevalence of toothpicks, and (not pictured) the use of flannels to clean ones hands and face before meals, toilet slippers, and disposable cotton gloves when doing dirty chores at home, are carried out in the eyes of God (the Sun Goddess and ancestors who are always watching) and themselves but are nearly invisible to other people.

The fig shaped enema above is from ichijiku.co.jp お取り下げご希望の場合は下記のコメント欄か、http://nihonbunka.comで掲示されるメールアドレスにご一筆ください。

Labels: autoscopy, japanese culture, Nacalian, 自己視

Thursday, June 11, 2015

Flashed Face Distortion Effect and Japanese Self-Caricaturization

What is it to identify with a self-representation? Many psychologists claim that in order to have or cognise a self we need to see it from the point of view of another within self, "the generalised other" of Mead, the "super-addressee" of Bakhtin, the "alter ego" of Derrida, the "Other" of Lacan, the "impartial spectator" of Smith, "the third person perspective" of Mori (1999), and the "super ego" of Freud.

Bataille (1992, p31) for example says "We do not know ourselves distinctly and clearly until the day we see ourselves from the outside as another."

The Flashed Face Distortion (FFD) effect (Tangen, Murphy, & Thompson, 2011) is a trippy newly discovered illusion in which when faces are flashed side by side we seem distorted, to an extent in caricature (see videos here and here).

It is not clear why. I suggest that it is probably that this caricaturization of faces is not limited to times when faces are flashed, but that we become aware of the caricaturisation when faces are flashed.

Still more recent brain neuro-imaging research (Wen and Kung, 2014) finds that the FFD effect is mediated by at least two neural networks: "one that is likely responsible for perception and another that is likely responsible for subjective feelings and engagement".

Why should subjective feelings and engagement processing take place? Again, it is not clear to me, but it seems likely that "subjective feelings and engagement" would differ for ones own face as opposed to the faces of others.

I created therefore a similar video except with my own face as one of the target faces. The video is far from ideal (as you can see) but it seems that the FFD is much weaker in this situation. The face that I am comparing various versions of my own face to is only slightly distorted or caricaturized whereas my own face does not appear to be caricaturized at all. I presume that this is a function of a variation in subjective feelings and engagement, and because I do not see my own face as the face of another, and either do not bother or feel inclined to caricaturize my own face. But then, I don't think of my face is my self. I think of that which is described by my self narrative as my self.

I hypothesize that from the way in which Japanese enhance their self representations, from the way it is claimed that their "mask" is the centre of their persona (Watsuji, 2011), and from in their self-enhancing self-manga ("jimanga") that Japanese will feel the Flashed Face Distortion (Tangen, Murphy, & Thompson, 2011) effect even when watching a video of their own faces. This is because they are seeing their own face as another and this is, paradoxically, a condition of seeing ones face as ones "self."

Bibliography

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Eds., V. W. McGee, Trans.) (Second Printing). University of Texas Press. Retrieved from pubpages.unh.edu/~jds/BAKHTINSG.htm

Bataille, G. (1992). Theory of Religion. (R. Hurley, Trans.). New York: Zone Books.

Derrida, J. (1978). Edmund Husserl’s origin of geometry: An introduction. U of Nebraska Press. Retrieved from books.google.co.jp/books?hl=en&lr=&id=pW9PQxAOo0s...

Freud, S. (1961). The ego and the id. Standard Edition, 19: 12-66. London: Hogarth Press.

Heine, S., Lehman, D., Markus, H., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard?. Psychological Review. Lacan, J. (2007). Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English. (B. Fink, Trans.) (1st ed.). W W Norton & Co Inc.

Leuers, T., & Sonoda, N. (1999). The eye of the other and the independent self of the Japanese. In Symposium presentation at the 3rd Conference of the Asian Association of Social Psychology, Taipei, Taiwan. Retrieved from nihonbunka.com/docs/aasp99.htm

Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist (Vol. 1). The University of Chicago Press. Nelson, T. O., Metzler, J., & Reed, D. A. (1974). Role of details in the long-term recognition of pictures and verbal descriptions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 102(1), 184–186. doi.org/10.1037/h0035700

Mori, 森, 有正. (1999). 森有正エッセー集成〈5〉. 筑摩書房.

Smith, A. (1812). The theory of moral sentiments. Retrieved from books.google.co.jp/books?hl=en&lr=&id=d-UUAAAAQAA...

Takemoto, T. (2002). 鏡の前の日本人. In 選書メチエ編集部, ニッポンは面白いか (講談社選書メチエ. 講談社.

Tangen, J. M., Murphy, S. C., & Thompson, M. B. (2011). Flashed face distortion effect: Grotesque faces from relative spaces. Perception-London, 40(5), 628. Retrieved from expertiseandevidence.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/TanMu...

Tversky, B., & Baratz, D. (1985). Memory for faces: Are caricatures better than photographs? Memory & Cognition, 13(1), 45–49. Retrieved from link.springer.com/article/10.3758/BF03198442

Wen, T., & Kung, C. C. (2014). Using functional magnetic resonance imaging to explore the flashed face distortion. Retrieved from jov.arvojournals.org/data/Journals/JOV/933545/i1534-7362-...

Watsuji, T. (2011). Mask and Persona. Japan Studies Review, 15, 147–155. Retrieved from asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies-review/jo...

Labels: autoscopy, culture, japan, japanese culture, self, 日本文化, 自己, 自己視

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Big Ben: Japanese boasting and sex

Linguistic self-enhancement has generally been considered to be rather disgusting in Japan, or at least something that the Japanese have avoided. In my experience, and in historical accounts of Western impressions of Japan, boastfulness is almost completely, and notably, absent.

One of the few accounts of Japanese boastfulness is that of a highly Westernised scholar of things Western (rangakusha). After several months in captivity in Japan, the Russian spy Vasiliĭ Mikhaĭlovich Golovin remarked in 1811 that the Japanese geometrician and astronomer, Mamia Rinso (Mamiya Rinzo) "manifested his pride, however, by constant boasting of the deeds he had performed, and the labours he had endured." (Golovin, 1824, p284) but further that, "I must here remark, that this was the first Japanese ventured, in our presence, to swagger and assume // importance on account of his military skill, and his vapouring made not only us but even his own countrymen sometimes laugh at him. " (Golovin, 1824, pp. 285-286). In other words, the only Japanese person to boast, in Golovin's experience, was one who had been influenced by Western culture.

I have found two other records of instances of boastfulness in Japan in the pre-twentieth century historical record and both of them relate to sex.

"One old couple, who kept one of these shops, we were on intimate terms with; that is to say, we seldom passed without a few words to them. One day, seeing the old woman by herself, we asked her wherever husband was, and were told that she supposed 'he was after the girls', after which she laughed, as if delighted at the idea of having such a gay old dog for a spouse...

The next time we visited the shop, we rallied the old fellow on being such a gay Lothario; be he did not seem as proud of the reputation as his wife was, and indignantly declared the aspersion cast on him to be totally without foundation. We were half inclined to believe him, and even now think that the old woman's statement may have only been a vainglorious boast"(Cortazzi, 2013,, p67)

Edward de Fonblanque writes, in 1860, of another rare instance Japanese boastfulness, which is also sexual.

"Nor were business wants alone consulted, for the Government had considerately provide a magnificent building, all lacquer and caving and delicate painting, in which the Tojin [Foreigner] might pass their leisure hours in the company of painted musume [literally daughter, but the meaning her is girl], dressed in gorgeous robes, and coifées in the most wonderful manner.

I visited the Gankiro, taking the precaution to go there in broad day, and for my character's sake, in good company, and was a little startled at the systematic way in which the authorities conduct this establishment. Two officers showed us over the building, and pointed out its beauties which as much pride as if they were exhibiting an ancient temple sacred to their dearest gods. This was the court-yard; that was to be a fish-pond with fountains (the building was still incomplete at this time); in this room refreshments might be procured -that was the theatre; those little nooks into which you entered by a slide panel in the wall were dormitories, encumbered with no unnecessary furniture, there, affixed to the walls, was the tariff of charges, which I leave to the imagination; and in that house, across the court, seated in rows on the verandah, were the moosmes themselves. We were invited to step over for its was only under male escort that they might enter the main building? My curiosity had, however, been sufficiently gratified and I departed, quite ready to believe in anything that might hear as to the morals of the Japanese. (Cortazzi, 2013, p274.)

The Japanese are perhaps similarly reserved towards boastfulness and sexuality. Japanese humour, unlike that of the British, rarely revolves around innuendo. But in my experience (and research on the latter), both sexuality and boastfulness do appear when the Japanese have been drinking.

For example when attending a party with some Japanese sports persons, I found myself invited to drink at a table of similarly inebriated Japanese. It was late in the day, we had all had a few glasses of sake. One gentleman asked mischievously "So you are English? (omitting the subject and particles) England has Big Ben doesn't it? / You have a big ben don't you?" (イギリス人ですか。*ビッグ・ベン*はありますよね?). I think my host repeat "big ben", nodding in a conspiratorial way for emphasis. This was a very rare case of innuendo and inviting the opportunity to boast, once again on a sexual topic, which from a Japanese perspective may regarded, with some disdain - but at times enjoyment - to be of similar ilk.

Is there any inherent connection between linguistic self-enhancement and sex? Or on the contrary between visual self-enhancement and the storge appreciation of cuteness? Some theoreticians of language, its origins and merits suggest that it may have something do with peacocking. Derrida argues that linguistic thought, as self addressed love letter, is like onanism. One of the characteristics of linguistic as opposed to visual self-enhancement is that it takes places inside rather than outside the head. While linguistic self love becomes silent, ashamed, and interior (see Vigotsky on self-speech and the way it becomes hidden) visual self-love always presupposes an exterior, viewer. Does the interiority of self-serving interior dialogue, knowing oneself via ones self-narrative, imply or promote a sexual "autoaffection"? I tend to think so.

I think I told my hosts that I had not seen Big Ben. Lame!

Image of Big Ben from Wikimedia

Cortazzi, H. (2013). Victorians in Japan: In and around the Treaty Ports. A&C Black.

Golovnin, V. M., Rīkord, P. Ī., & Shishkov, A. S. (1824). Memoirs of a Captivity in Japan, During the Years 1811, 1812, and 1813: With Observations on the Country and the People. H. Colburn and Company.

Labels: japanese, japanese culture, logos, occularcentrism, sex, 日本文化, 自己視

Friday, April 24, 2015

Do Foreigners make more Gestures?

It is a common perception in Japan that non Japanese make more and more exaggerated gestures while talk to each other than Japanese. This excerpt from a comic (Oguri, 2010, p.8) on the differences between a Japanese woman and her foreign husband includes the copy "Well of course foreigners have much more exaggerated gestures, as we all know."

On the other hand, Western perception of Japanese gestures is mixed. On the one hand there is a perception that the Japanese wear for instance a "mask of inscrutability" and are covered "beneath courteous reserve" (Craigie, 2004, p. 172). In Japan "people have to suppress their true feelings practically all the time" (Rice, 2004, p144).

At the other extreme, caricatures of Japanese such as in the Directors Cut of Grand Blue where a Japanese diving coach works his diver so hard the later feints, or Isuro "Kamikazi" Tanaka played by Takaaki Ishibashi "who helps excite the team" with his frantic overwrought gestures in Major League 2. Japanese gestures can appear exaggerated to Westerners too. Part of the reason for both Japanese and Westerners thinking that the other's gestures are exagerrated is likely due to the fact that the gestures themselves are different, and phenomena to which one is not accustomed stand out.

Surprising though it may seem to Japanese, research on nodding beat gestures (Maynard, 1987: see also Kita, 2009) generated during speech production, showed that Japanese approximately four times more nods, once ever 5.57 seconds whereas Americans nod only every 22.5 seconds (informal study, Maynard, 1987, p602, note 4). Both Japanese and Americans nod at the beats, and baton touch turn-taking position. But Japanese nod, not only at these times and in the back channel, but also in the middle of their own statements.

So who does make more gestures. A quick comparison of a couple of wedding speakers in Japanese in English on Youtube demonstrates the source of this difference. Americans wave their hands more and use obvious exaggerated, semi iconic facial gestures (like those caricatured above) more liberally but Japanese use a great deal of nodding and bowing to emphasise what their are saying, demonstrate sincerity and as beats. No wonder Japanese speakers get "shoulder ache" (katakori). Conclusive research on the relative importance of gesture remains to be done.

The Japanese, like Italians, also have a wide lexicon of iconic gestures that can be used in place of speech. And as always, I argue that Japan is NOT a high context culture (Hall, 1966; Honna, 1988: see Tsuda, 1992) but that visual communication is the central media and in Japan language is considered to be part of the context. This means that language will often be used to express flattery and other pleasantries (tatemae, such saying "I'll think about it") in stead of "no". Whereas the true meaning (honne) is expressed in the face, posture, pause and expression. Returning to Major League 2, for all his exaggeration, famed Japanese comedian Takaaki' Ishibashi's caricature of the Japanese is faithful. His expressions move from one form to the next like a Kabuki actor, or Kyari Pamyu Pamyu, nothing is left to chance, there is in Barthes' words "perfect domination of the codes" (1989, p.10)

The closest that a Western scholar gets to recognising that gesture and the non-verbal could be central to self and meaning in Japan is Roland Barthes' "Empire of Signs" (1983) (based in part on the observations of Maurice Pinguet).

Now it happens that in this country (Japan) the empire of signifiers is so immense, so in excess of speech, that the exchange of signs retains of a fascinating richness, mobility, and subtlety, despite the opacity of the language, sometimes even as a consequence of that opacity. The reason for this is that in Japan the body exists, acts, shows itself, give itself, without hysteria, without narcissism, but according to a pure - though subtly discontinuous - erotic project. It is not the voice (with which we identify the "rights" of the person) which communicates (communicates what? our-necessarily beautiful-soul? our sincerity? our prestige?) but the whole, body (eyes, smile, hair, gestures, clothing) which sustains with you a son of babble that the perfect domination of the codes strips of all regressive, infantile character. To make a date (by gestures, drawings on paper, proper names) may take an hour, but during that hour, fur a message which would. be abolished in an instant if it were to be spoken (simultaneously quite essential and quite insignificant), it is the other's entire body which has been known, savoured, received, and which has displayed (to no real purpose) its own narrative, its own text. (Barthes, 1983, p.10)

Barthes comes close. He can't help making a "text" of the Japanese body, the only way that he can admit it has meaning since in his hierarchy only language can truly mean (see Barthes, diagram p. 113).

Barthes famously claims that "the centre (of Japan, the Japanese subject) is empty," and in the above passage that its communication has "no real purpose," but at the same time Japan has forced him to question the purpose of his own vocalisations. And he is wrong that the body talk is erotic. He is talking to and about himself. Japanese signs and selves are cute. The relative absence of words, and the erotic beguiled him to conclude that the centre of Japan is empty. The self and centre of Japan does not have or needs words, but is is far from empty rather visual and raging, fury Kyari Pamyu Pamyu barfing eyeballs full.

Finally, while Merbihain's 93% (Mehrabian & Ferris, 1967) has been rejected even by Mehrabian (Mehrabian, 1995: see Lapakko, 1997) it is clear that non-verbal communication is extremely important. Bearing this in mind the pressing question for me is how Hall (1976) had the gall (!) to claim that those cultures that do not see language as central to human communication are "high context" at all? That nonverbal communication is contextual assumes that language is central, privileged when in fact in Japan, it is often the reverse.

Taking one example, Hall claims that in Japan people expect more of others.

"It is very seldom in Japan that someone will correct you or explain things to you. You are supposed to know and they get quite upset when you don’t. ... People raised in high context cultures expect more of others than to the participants in low-context systems. When talking about something that they have on their minds, a high context individual will expect his interlocutor to know what is bothering him, so that he doesn't have to be specific." (Hall, 1976, p98)

Do Westerners really expect less of others?

I find that in interaction with Japanese I often expect them to have heard my words, the generalities that I have stated, and to apply them across multiple situations. I expect this of them. When I bothered about some situation where previously expressed verbal wishes and requirements are not being met, I expect others to know and get quite upset (like a arrogant fool) when they don't. Americans expect others to understand their generalities - their linguistic expressions - as Japanese expect others to look, mirror and behave appropriate to the situation. This is due to the fact that the central mode of meaning is different not because members of either culture place greater or lesser expectations upon others.

Dumping the hierarchy of the old Western text/context word/world dualism will help us to understand the Japanese and ourselves.

Bibliography

Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies. (A. Lavers, Trans.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Barthes, R. (1983). Empire of Signs. (R. Howard, Trans.). Hill and Wang.

Craigie, R. (2004). Behind the Japanese Mask: A British Ambassador in Japan, 1937-1942. Routledge.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond Culture. Anchor Press.

Kita, S. (2009). Cross-cultural variation of speech-accompanying gesture: A review. Language and Cognitive Processes, 24(2), 145–167. doi.org/10.1080/01690960802586188

Knapp, M., Hall, J., & Horgan, T. (2013). Nonverbal Communication in Human Interaction. Cengage Learning.

Lapakko, D. (1997). Three cheers for language: A closer examination of a widely cited study of nonverbal communication. Communication Education, 46(1), 63–67. Retrieved from www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03634529709379073

Maynard, S. K. (1987). Interactional functions of a nonverbal sign Head movement in japanese dyadic casual conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 11(5), 589–606. doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(87)90181-0

Mehrabian, A., & Ferris, S. R. (1967). Inference of attitudes from nonverbal communication in two channels. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 31(3), 248. Retrieved from psycnet.apa.org/journals/ccp/31/3/248/

Oguri, S. (2010). Dārin wa gaikokujin.

Rice, J. (2004). Behind the Japanese mask--: how to understand the Japanese culture-- and work successfully with it. Oxford: HowToBooks.

Labels: collectivism, culture, image, individualism, japan, japanese, japanese culture, 日本文化, 自己視

Monday, April 20, 2015

Reciprocal Resurrection of Simulacra

This essay explores the intersection between Derrida's Post Card (1987), and Baudrillard's simulacra (1995) in Western and Japanese culture: word/idea pairs and images respectively.

Most Western philosophers are unintentionally obfuscating. They want to tell their readers that it is okay, That the way we understand the world is not a grotesque lie. A few, larger French philosophers such as Baudrillard (1995) and Derrida (1987, 1998, 2011) attempts to pull the lie apart, to expose its untruth. But, because they are polite and the lie ingrained, they is not quite persuasive enough. Obfuscators take the mickey out of their "Parisian logic" (Mulligan, 1991).

In order to see oneself it is self-evident that one has to model the perspective of an other and or mirror. However, when talking about oneself to oneself, this need for another, real or simulated, is not apparent. Many clever people (I am thinking of Steven Heine e.g. in Heine, 2003) claim that face, or image is essentially for others whereas language, (that most social of media!) and our Western narratives selves are for ourselves.

Indeed, most Westerners think, that when they think they are thinking, talking simply to themselves (and not to Mel Gibson's Satan, above right). Seeing oneself requires a spatial distance that makes the alterity of self-observer far more apparent. But speaking, hearing oneself speak, does not seem necessarily to involve anyone else, real or imagined, at all. Derrida rejects this possibility forcefully (Garver, 1973).

The truth in my humble opinion, and experience is, that as Derrida argues, speaking to oneself does require an other, simulated or real. But few people, or atheists at least, seem to realise this. How can I convince folks of the truth, that self-narrative requires an other to be meaningful?

Derrida's gambit is something on the lines of the following.

When I talk about myself I use signs, signs like "Tim" and "I". Each time I say or think a sign I may be slurred or abbreviate but for the phoneme to mean, it needs to be one of a group of other iterations of the same sign. Signs are iterative. I can say Tim TIM Tm, tem, timu, timm, with all sorts of slurings and blurrings but for "tim" to mean me it must be member of the set of signs that are iterable. It must be one of the sayings of "Tim." "Tim" as a sign is a sign by virtue of the fact that it is recognisable and distinguishable from tin (can).

Therefore, Derrida opines, since signs have this property in themselves of being repeatable and recognisable their use implies a distance or disappearance of the subject that uses them. Derrida fundamental insight is I think that this iterability implies speech is no different from writing.

Mulligan (1998) is right to point out that it is going to be difficult to convince anyone that the iterability of signs implies anything threatening about the Western self. Conversely, the fact that signs are iterable (repeatable in time) is a phenomena that obfuscating philosophers have used as evidence for the existence of "presence:" the co-temporal, co-presence of "ideas".

That signs are essentially "iterable" is a proposition that Derrida gets from Husserl who he paraphrases in the following way.

"When in fact I effectively use words, and whether or not I do it for communicative ends (let us consider signs in general, prior to this distinction), I must from the outset operate (within) a structure of repetition.... A sign is never an event, if by event we mean an irreplaceable empirical particular. A sign which would take place but “once” would not be a sign; a purely idiomatic sign would not be a sign. A signifier (in general) must be formally recognizable in spite of, and through, the diversity of empirical characteristics which may modify it. It must remain the same, and be able to be repeated as such, despite and across the deformations which the empirical event necessarily makes it undergo. A phoneme or grapheme is necessarily always to some extent different each time that it is presented in an Operation or perception. But, it can function as a sign, and in general as language only if a formal identity enables it to be issued again and to be recognized. (Derrida, 1967, p55—56; Derrida, 2001, p.42 see Mulligan, 1992, p.5.)

Derrida also states more pithily “a sign which would take place but `once’ would not be a sign”

Hansen (1993) traces this distinction too, between sign tokens or instantiations and signs, and points out Western philosophers since Plato and Aristotle have claimed that (Aristotle writes, see Hansen, 1993) "spoken sounds are symbols of affections in the soul, and written marks symbols of the spoken sounds. And just as written marks are not the same for all men, neither are spoken sounds. But what these are in the first place signs of-affections in the soul-are the same for all; and what these affections are likenesses of - actual things - are also the same."

This is basically the same argument as presented by Husserl about 2000 years earlier. Our feeling of their being identity in difference, of a unity, despite multiple instantiations, demonstrates to us that there must be existences underpinning them. Words are somehow the same every time we use them. This is not true, but we feel it strongly.

I think it is possible to be far more persuasive, and threatening, by taking a detour through Japanese culture. The use of Japanese culture as an analogy is similar to writing a book of self addressed postcards (Derrida, 1987) to illustrate the weirdness of self-addressed speech, except that the Japanese, unlike the postcard writer of Derrida's book (ibid), are not fictional, and I believe they send themselves blank postcards - images without words (Kim, 2002) in the form of selfies, purikura (Toriyama et al., 2014), souvenir photos (kinenshashin: see Davidson, 2006 p36), third person memories (Cohen, Hoshino-Browne, & Leung, 2007), and autoscopic video games (Masuda and Takemoto in preparation).

I argue that whereas Westerners hear a shared, identical unity behind multiple slightly differing sound tokens, Japanese may feel the same way about images. A copy of a shrine, horse, bonsai tree, karate form or a face, though it changes in each instantiation call to the Japanese mind a similar sense of unity as called to the mind of Westerners when they hear words.

Despite, upon consideration there being a plurality of word phenomena, each instantiation is as good as the others. No word is inferior to another, no word is a copy of another word, since they all refer to a (illusionary) underlying unity. All words are authentic because they match up to ghostly metaphysical meanings. Westerners until Dennet (1992) find it difficult to deny the existence of these idealities, because they are one of their number. Our self, existed traditionally as an idea in the mind of God, or according to Dennet, who somehow manages to obfuscate even as he reveals the truth, is an abstraction or fiction.

Similarly Japanese may be able to feel that "foreign villages" (in Japan - gaikokumura 外国村) are as good or the same as villages abroad, or that video tapes of a deceased grandfather require funeral services just as did the body (image) of their grandfather, or that a sculpture or even a picture of a horse (ema 絵馬) is as pleasing to a god as real horse, or that a mask or face can represent the underlying unity of a person (Watsuji, 2011).

Nowhere are simulacra, or authenticopies, more visible than the Japanese religion, Shinto. Shinto shrines, especially that of the sungoddess are rebuilt (senguu 遷宮) made in miniature for household shrine shelves (神棚), and replicated (e.g. the replica of Ise shrine in Yamaguchi city's main shrine) but in all cases thought to be authentic. Japanese deities are infinity divisible (bunrei 分霊) and and transportable (kanjou 勧請) to be enshrined elsewhere (bunsha 分社). Originally this would require the copying of the object felt to contain the spirit/deity (goshintai 御神体), but more often now simply by stamping the characters on a piece of wood, card or paper to form a sacred token (神符), as in the case of the sacred talisman that serve to transport the deity into household shrines (ofuda お札) and inside protective amulets (omamoriお守り). Sometimes these sacred stamped tokens (shinpu/ofuda神符/お札) were felt to fall from the sky causing great merriment, singing, dancing and tourism("("good isn't it?" or "hang loose" ええじゃないか). Just as the Lords prayer on the lips of one bishop is the same as that on the other so the stamped names of Japanese deities are the same in all their instantiations. Conversely, in Japan words without material representation are felt to be hot air, as the Jesuits lamented being required to bring presents and not express gratitude in words.

It does not matter that faces age, seals smudge, or that there are minor differences between sculpted and real horses, just as it does not matter that I might say my name, or I, with a hoarse voice (To the Japanese the voice is always horse..!). That is not to say that the Japanese are fully identified with their bodies. Traditionally the Japanese were also aware of the field of vision, that which which sees, the mirror as soul. But that space is no different from that which is seen, or rather contains the authenticopies as they are, without their need to be unified and represented by an idea.

Narcissus is a fool for mistaking his reflection for himself but there is identity, Echo, in his voice (Brenkman, 1976). Likewise Susano'o is a fool for repeating his words but there is identity, Amaterasus, in his image. Iterability in time is like copiability in space - there is a ridiculous distance. When Narcissus falls in love with his self reflected in the water we want to shout "but that isn't you!" There is an obvious plurality, a painful not-one-ness. It is as ridiculous to a Japanese person to hear someone speaking to themselves or praising themselves as it is to a Westerner watching Narcissus love his image. in each case evaluating subject can not escape from evaluated object, and the loop is felt incomplete.

These differences in perception depend upon culture not some inherent superiority of one or other media. Writing is no more a record of speech than speech refers to writing.

This is due to the nature of the Other being simulated in the mind. There never was a layer of ideas, or metaphysical realm, just a partner in the heart. Westerners from Plato to Baudrillard (1995) tell us that is God that In the West we feel (and or do not feel) as if a super-addressee is always listening and Japanese feel (and or do not feel) as if someone is always watching.

By "and or do not feel" I mean that the Other is both felt and hidden. That on the one hand I "feel" someone is listening make this preposterous self-speech that I do, even in my head, meaningful, pleasurable but on the other if the door were to open and I were to see what I am speaking to, I would recoil in horror. So in that sense I do not feel the presence of the other. I will come back to this.

I think that the two forms of ridiculous distance should start to erase each other in those that experience them. The way in which Post Cards and images destabilise the structure of the word/idea complex is also discussed by Baudrillard (1995).

Baudrillard writes "[Iconoclasts] predicted this omnipotence of simulacra, the faculty simulacra have of effacing God from the conscience of man, and the destructive, annihilating truth that they allow to appear—that deep down God never existed, that only the simulacrum ever existed, even that God himself was never anything but his own simulacrum—from this came their urge to destroy the images.rage to destroy images." (1995, p4)

Baudrillard's term "simulacra" seems too broad, being used to mean words, images, simulated subject positions and even perhaps the imminent universe. Nevertheless he has a point. It seems to me that the two types of simulacra that I differentiate (Western words, and Japanese images or "authenticopies") should have a tendency to draw attention to the limitations of each, and not so much erase but resurrect (!) or make people aware of God, in one person or another, as intra-psychic other.

By consideration of Edo period artwork and research on Japanese artistic representation (Masuda, Wang, Ito, & Senzaki, 2012) third person memories (Cohen, Hoshino-Browne, & Leung, 2007) the Other of the Japanese is not "in the head" but outside of it, a spatial distance but still in their psyche, that is to say a simulated, undead viewpoint. Japanese ancestors look down and protect. Though simulated, I don't think they could ever be as dead as words and images since it is a simulated subject position, but in the title I am using "simulacra" to be simulated subject positions, a viewer, or hearer. It is really these that have ensured the meaning of Western Words and Japanese images.

Theists experience these subject positions as their Gods: ancestors or Amaterasu, and Jesus. Atheists may experience them as the monsters shown above Sadako of "Ringu", (Nakata, 1998) and Satan of "The Passion of the Christ" (Gibson, 2004).

When Baudrillard further writes "If they [iconoclasts] could have believed that these images only obfuscated or masked the Platonic Idea of God, there would have been no reason to destroy them. One can live with the idea of distorted truth. But their metaphysical despair came from the idea that the image didn't conceal anything at all, and that these images were in essence not images, such as an original model would have made them, but perfect simulacra, forever radiant with their own fascination. Thus this death of the divine referential must be exorcised at all costs." (1995, p4) he is correct to say that images do not require a second term, a "divine referential:" ideas. However, both word/ideas and images do require a third term a simulated hearer/view point. Images exist in the mind of their god unmediated.

Returning to the way in which the Other is and is not here.

Husserl is adamant that no one is listening to thought, and it is precisely this fact, coupled with the fact that he can yet understand himself, that convinces him that something other than what happens when we speak to others must be going on. "He believes that he finds pure expression [of another layer of ideal things] in interior monologue because, in interior monologue, my thoughts seem to be present to me at the very instant that I say them." (VP, p. xxv). This argument convinces cleverer people than me, such as Mulligan.

When a Japanese person is looking at a mirror (which she may not need), or imagining herself, she may feel that that the person in the mirror or the image in her mind is herself. Looking at a Japanese person looking at a mirror I may want to to say "no, that is not you! Look you are on this side of the mirror not that thing over there!" But the Japanese lady is cleverer than me. She "knows", like Husserl "knows", there is no one else in her head, so there is no way someone can watch from the wings to claim "You are not the person reflected in the mirror."

To me sight is always seen by someone (an eye) just as to the Japanese (Mori, 1999) language is always heard by someone (an ear). Language in Japan is always contextual. Sight in the West is always contextual. Conversely, the "third person perspective" (Mori, ibid) exists in language in the West, and in those birds eye views that the Japanese see, feel and represent.

The experience of hearing oneself speak proves to Husserl that speech can be heard and understood without another listener (other than the one speaking) because he feels he is absolutely alone. Specifically Husserl can understand the word "I" to refer to himself.

The experience of seeing oneself imagined proves to Japanese that images can be seen and understood without another viewer (other than the one seen) because she feels she is absolutely alone facing the mirror. Specifically she can understand the image to be herself.

Addressing Husserl, Derrida says that consciousness is temporised, and that the other needed and simulated to understand the interior I is deferred in time. "You don't realise that you are writing letters to yourself in the future/ reading letters from yourself in the past." You are not alone at the level of simulacra.

Addressing the Japanese person I want to say that consciousness is spatialised, and that the other needed and simulated to understand the interior self image is distanced. "You don't realise that you are signing to yourself at a distance/ seeing yourself from a distance." You are not alone at the level of simulacra.

It is so obvious to me, a Westerner, that one can see imagine oneself from the outside. That is obvious to the Japanese too. But if the Japanese have an extra viewpoint that is horrifying, then erasing that viewpoint, and yet at the same time viewing themselves from it, they can misunderstand themselves as that which is seen, forgetting that they are not turning to meet the gaze of a monster, distanced, in the image.

It is obvious to a Japanese person that I can defer understanding, when I practice justifying myself for instance (Haidt, 2001). That is obvious to me too. But I if I have an extra ear-point, a super-addressee that is horrifying, then erasing that ear-point, and at the same time hearing myself from it, I can misunderstand myself as that I am that which is said, forgetting that all I am doing is deferring speaking to a monster deferred. Who am I going to meet?

All is needed for self is an other in mind which is too horrible to be fully aware of. That one is aware of but can not admit of, nor gaze at. Someone you know is there behind a door. Someone that will open a door one day, when Japanese people go somewhere.

That there are two ways of doing this auto-affection (which are interlinked) may at the boundary between the two make obfuscation apparent.

Am I oversimplifying? Regarding Derrida, his translator writes "In other words, if we think of interior monologue, we see that difference between hearing and speaking is necessary, we see that dialogue comes first. But through dialogue (the iteration or the back and forth) of the same, a self is produced. And yet, the process of dialogue, differentiation-repetition, never completes itself in identity; the movement continues to go beyond to infinity; the movement continues to go beyond to infinity so that identity is always deferred. always a step beyond." That sounds very complicated.

But if self-speech is just practice speech (Haidt, 2001) that we do all the time before meeting people to whom we explain ourselves to, then self speech is surprisingly mundane. Self speech might be compared to a love-song to a lover that we'll never meet, or a series of amorous post cards to yourself in the future (Derrida, 1987), or those letters that remain unopened in a Chronicle of a Death Foretold.

Bibliography

Baudrillard, J. (1995). Simulcra and Simulation. (S. F. Glaser, Trans.). Univ of Michigan Pr.

Brenkman, J. (1976). Narcissus in the Text. Georgia Review, 30(2), 293–327. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/41399656

Cohen, D., Hoshino-Browne, E., & Leung, A. K. (2007). Culture and the structure of personal experience: Insider and outsider phenomenologies of the self and social world. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 1–67.

Davidson, C. N. (2006). 36 Views of Mount Fuji: On Finding Myself in Japan. Duke University Press.

Dennett, D. C. (1992). The Self as a Center of Narrative Gravity. Self and Consciousness: Multiple Perspectives. Retrieved from ase.tufts.edu/cogstud/papers/selfctr.htm

Derrida, J. (1987). The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. (A. Bass, Trans.) (1 edition). Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J. (1998). Of grammatology. (G. C. Spivak, Trans.). JHU Press.

Derrida, J. (2011). Voice and Phenomenon: Introduction to the Problem of the Sign in Husserl’s Phenomenology. Northwestern Univ Pr.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814. Retrieved from psycnet.apa.org/journals/rev/108/4/814/

Hansen, C. (1993). Chinese Ideographs and Western Ideas. The Journal of Asian Studies, 52(02), 373–399. doi.org/10.2307/2059652

Heine, S. J. (2003). An exploration of cultural variation in self-enhancing and self-improving motivations. In Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 49, pp. 101–128). Retrieved from books.google.co.jp/books?hl=en&lr=&id=UCl0stabm54...

Husserl, E. (2001). Logical Investigations Volume 1 (Revised Edition). London ; New York: Routledge.

Kim, H. S. (2002). We talk, therefore we think? A cultural analysis of the effect of talking on thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 828.

Masuda, T., Wang, H., Ito, K., & Senzaki, S. (2012). Culture and the Mind: Implications for Art, Design, and Advertisement. Handbook of Research on International Advertising, 109.

Mulligan, K. (1991). How not to read: Derrida on Husserl. Topoi, 10(2), 199–208.

Watsuji, T. (2011). Mask and Persona. Japan Studies Review, 15, 147–155. Retrieved from asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies-review/jo...

Toriyama et al. 烏山史織, 齋藤美保子, カラスヤマシオリ, サイトウミホコ, KARASUYAMA, S., & SAITO, M. (2014). Awareness of Purikura in youths: A comparison of high school and university student’s. 鹿児島大学教育学部教育実践研究紀要=Bulletin of the Educational Research and Practice, Faculty of Education, Kagoshima University, 23, 83–94. Retrieved from ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/120005434882

Mori, A. 森有正. (1999). 森有正エッセー集成〈5〉. 筑摩書房.

Labels: cultural psychology, culture, derrida, eye, horror, image, japan, japanese culture, 日本文化, 自己, 自己視

Sunday, April 05, 2015

Funerals for Video Tapes and Symbolic Immortality

The image above is part of an advert by a company offering VHS (etc) analogue tape to DVD dubbing services. People send their tapes and photograph albums to the company, which converts the analogue formats to digital and sends the data back to the customers in DVD form.

But what happens to the video tape itself? Should it just go in the trash? What happens if the video tape is of someone deceased? This Japanese company offers an additional service, in the case of one video tape at twice the price of the dubbing itself, funereal mourning rites, at an affiliated Buddhist temple. Customers pay for about $30 USD for a Buddhist priest to chant Buddhist prayers over up to twenty of their VHS video tapes, several times, before eventually disposing of them.

This question would not occur to a Westerner. But in Japan there is a far greater reticence towards destroying visual representations of people since these visual representations are far closer to the persons videoed. Similarly, for example there are also funereal rites for dolls in Japan because dolls are far more felt to have had lives.

So, is there a Nacalian transformation? Do Westerners pay our respects towards diaries, or voice recordings, especially of the dead, for instance?

Funeral rites for visual representations of persons (real or otherwise) may suggests a desire for visual representations of persons to live on - to go to a pictorial heaven as it were, where images live forever in an eternal light.

While I am unaware of a direct transformation, where Westerners pay respect to the linguistic representations of the dead, while they are alive it is found that at least Westerner strive towards 'symbolic immortality,' in the face of "mortality salience" - being required to think about their own death.

When required to think about their death, humans -- or at least Westerners -- attempt to live on in their narratives. The question as to whether Asians attempt to achieve "symbolic immortality" is controversial. Heine, Harihara, and Niiya (2002) found that Japanese do. Kashima, Halloran, Yuki, and Kashima (2004) found that mortality salience produced different effects in Japanese and Westerners. Yen & Cheng (2010) found that Taiwanese do not. Ma-Kellams and Blascovich (2012) found that Asians do other things in the face of death: rather than focus upon symbolic immortality they attempt to enjoy life more.

I hypothesise that Japanese would aim not for symbolic immortality but for vision-imaginable immortality. In the real world this may translate to the attempt to enjoy that picture book which is life more, or leave descendants that they can watch and protect forever. In the lab I hypothesise that Japanese will draw more positive "jimanga" (Takemoto, 2017) (prideful auto portraiture) should they be required to think about their death.

Heine, S. J., Harihara, M., & Niiya, Y. (2002). Terror management in Japan. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 5(3), 187–196. Retrieved from

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-839X.00103/full

Kashima, E. S., Halloran, M., Yuki, M., & Kashima, Y. (2004). The effects of personal and collective mortality salience on individualism: Comparing Australians and Japanese with higher and lower self-esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(3), 384–392.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2003.07.007

Ma-Kellams, C., & Blascovich, J. (2012). Enjoying life in the face of death: East–West differences in responses to mortality salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(5), 773–786. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0029366

Yen, C.-L., & Cheng, C.-P. (2010). Terror management among Taiwanese: Worldview defence or resigning to fate? Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13(3), 185–194.

http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2010.01328.x

武本, Timothy. (2017). ジマンガ:日本人の心像的自尊心を測る試み(Auto-Manga as Prideful-Pictures: An Attempt to Measure Japanese Mental Image Self-Esteem). 山口経済学雑誌= Yamaguchi Journal of Economics, Business Administrations & Laws, 65(6), 351–382. http://nihonbunka.com/docs/Jimanga.pdf

Labels: buddhism, culture, image, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, 日本文化, 自己, 自己視

Thursday, April 02, 2015

Graven Images as Expressions of Self

There is a strong tendency even among psychologists, to believe that the visual is presentational and external and therefore not really pyschological in the same way as linguistic thought.

There is no denying that the visual is external. The environment in which we were raised (Mori's fields and mountains), our faces or mask (Watsuji) are on our outsides as well. To say that the visual is psychological is not to deny its exteriority, but to assert the following:

1) One can imagine oneself and world of vision in ones psyche. This is obvious

2) In order to imagine oneself one needs the viewpoint of an Other who is physically external but simulated within the psyche.

3) Language likewise requires an other interluctor, who is external (or should be!) simulated within the self.

I think that the horror that (3) entails - that they are sharing their heads with someone, something else - is so great for atheisits at least, it tends to be rejected, or concealed behind claims of a metaphysical presence of "ideas," or "meanings."

Once one can accept these three assumptions however, it is clear that visual expressions are equally psychological and of self. In this video I introduce the dolls made by my wifes mother to express her aspirations for her granddaughters - things like health, wealth, happiness and a happy marriage - throught the use of graven images. In Japan I believe that these expressions are felt to be "paired-images" (guuzou,偶像) or like words, authenticopies of the aspirations which they represent. These are not worshipped in the same way as a Catholic worships Yahweh, but regarded fondly, important, and sincere. As such I think that they fall under the definition of graven image as defined by the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

http://www.scborromeo.org/ccc/para/2113.htm

Labels: autoscopy, cultural psychology, culture, cute, family, japan, japanese culture, kawaii, 日本文化, 自己, 自己視

Honest Japanese, Proud Americans?

In linguistic scales of self worth, such as self esteem, Japanese are inclined to rate themselves on average a little above the median point of the scale. This is to be expected if they are rating their worth honestly and accurately.

The above results show the self-esteem distribution of Japanese (who have never been abroad, since just visiting the west is inclined to inflate pride) and for North Americans (Canadians, I believe a US sample would be even more extreme). In the USA the only population that evaluates themselves realistically are the clinically depressed (Taylor and Brown, 1988).

When Japanese are asked to rate themselves using manga - a visual test of self worth - there is a similar self-evaluation distribution to Americans, quewed towards the positive, boastful side of the graph.

The above image is reproduced without permission from pages 776 and 777 from Heine et. al. (1999). I am always quoting this research so I felt that it should be viewable on the Internet, as it already is in pdf form but, I will cease and desist immediately should you require m(_ _ )m.

Bibliography

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard?. Psychological review, 106(4), 766.

humancond.org/_media/papers/heine99_universal_positive_re...

www.psych.ubc.ca/~heine/docs/1999universal_need.pdf

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1994). Positive illusions and well-being revisited: separating fact from fiction.

Labels: cultural psychology, japanese culture, self, specular, 日本文化, 自己, 自己視

Tuesday, March 31, 2015

The Gates of Hell

I wrote recently about the creation myth of Guam. To recap, it goes like this.

Human souls were all slaves in hell but due to a conflagration, one soul managed to escape to Guam where he made a human child out of soften rock and gave it a soul made of the sun. When the king of hell came looking for his lost soul he thought it must be that of the child and tried to bring him back down to hell, but hard as he tried, he could take the child to hell, because its soul was made from the sun.

The creation myth of Guam is almost a paraphrase of that of the Japanese in the Kojiki where it relates that soul of the Japanese is also made from the sun -- the mirror of the sun -- and that the creator of this sun-mirror-soul went to hell - or the underworld - and came back.

Indeed, the deities and heroes of Japanese mythology are always going somewhere rather under-worldly. Susano'o visits the Sun who hides in a cave with hellish consequences. Yamasachi HIko goes down to the kingdom in the sea. But they always manage to come back. And their soul remains, according Heisig's reading of Nishida, visual, self-seeing, in the light, made of the sun. How did the Japanese achieve this?

Consider first the alternative. What is hell or "the underworld." Having at last worked out what Derrida means by "mourning," and what Freud was hinting at by his "acoustic cap," I now realize that hell is that which was nearest and dearest to me, and where in large part I live. Hell is a place where there are dead people. I don't see them, I talk to them. I talk principally to a dead woman, a woman who was never really alive, or even a woman, in my head. This is the essence of the narrative self. Mead calls it a Generalized other, Bakhtin a "super-addressee," Freud the super ego, Lacan (m)other, Adam Smith "the impartial spectator" and I think that the Bible refers to it at first as "Eve." A dead woman to keep you company, for you to get to know, and have relations with. Hell indeed. (There is a Christian solution, that involves replacing the internal interlocutor, with another "of Adam" and, quite understandably, hating on sex.)

So how did the Japanese manage to avoid talking to the dead woman? There are various scenes in the mythology. Izanagi runs throwing down garments which change into food (this chase with dropped objects turning into things that slow down ones attacker is repeated all over the world. I have no idea what it means). And in the next myth cycle, as mentioned recently, the proto-Japanese get the woman to come out of her cave with a sexy dance, a laugh, a mirror and a some zizag pieces of paper to stop her going back in again. In this post I concentrate on the last two, shown in the images above.

The mirror was for her to look at her self. She became convinced it was her self and told the Japanese to worship it as if it was her, which they had done every since, eating her mirror every New Year, until quite recently.

The zigzag pieces of paper have two functions. One in purification rituals where I think they are used to soak up words since the woes of humans are in large part the names given to those woes (e.g. of the proliferation of mental illnesses). As blank pieces of paper are waved over Japanese heads a priest may also chant a prayer about how impurities were written onto little pieces of wood which are used to take all them back to the underworld where they belong.

The other use of zigzag strips is that they can also be used for all the sacred stamped pieces of paper which are used to symbolize identity in Japan, and to encourage the Japanese to realise that words are things in the world - not things that should be in your head. And until recently (Kim, 2002) the Japanese managed to keep the words out of their mirror soul.

But alas it seems to me that the Gates of Hell are opening and the children of the sun are in danger of being sucked back in. How might this be achieved?

The following is the beginning of a recent Japanese journal article (Iwanaga, Kashiwagi, Arayama, Fujioka & Hashimoto, 2013) in my translation (the original is appended below) which, intentionally or not, aims to import Western psychology into Japan.

"As typified by the way in which the phrase "dropouts" (ochikobore) was reported in Japanese newspapers and became a social problem initiated by the report from the national educational research association in 1971, the remaining years of the 1970's saw the symbolic emergence of a variety of educational problems. Thereafter there was an increase in problems such as juvenile delinquency (shounen hikou), school violence (kounaibouryoku), vandalism (kibutsuhason), academic slacking (taigaku), the 1980s saw the arrival of problems such as the increasingly atrocious nature of adolescent crimes including the murder of parents with a metal baseball bat (kinzokubatto ni yoru ryoushin satugaijiken) and the attack and murder of homeless people in Yokohama (furoushashuugekijiken), domestic violence, and bullying, and then in the 1990's the seriousness of educational problems such as the dramatic increase in delinquency (futoukou), dropping out of high school (koukou chuutai), and a series of murders by adolescents steadily increased. "(Iwanaga, Kashiwagi, Arayama, Fujioka & Hashimoto, 2013, p.101)

As you can see the writers are partially aware that all the "problems" that have assailed Japan since the 1970's are in part an "emblematic emergence" or impurities. While some of these problem have worsened in fact, many of them are simply the sort of thing that should be tractable to purification. The Japanese are not for instance assailed by an increase in adolescent crime which as Youro (2003) in his book "the Wall of Foolishness" points out, has decreased and become less violent post war in Japan.

The Japanese are assailed by a variety of emblems - names of problems - which nonetheless cause real suffering.

If it were only this plague of names of social ailments swarming out of hell, then I think that the Japanese would be

fairly safe. The problem is that the above paper, Japanese Education Department, and a great many Japanese clinical psychologists and educators, are offering the Japanese the infernal equivalent of the mirror: self-esteem, a dialogue with the dead woman that allows one to enjoy "mourning," telling oneself for instance, that one is beautiful as one stuffs one's face. The title of the paper (Iwanaga, Kashiwagi, Arayama, Fujioka & Hashimoto, 2013) is "Research on the Determining Factors of the Present State of Childrens' Self-esteem," in which the authors blame the lack of Japanese self-esteem -- the Japanese hardly sext themselves at all-- on the emergence of all the social ailments. What fiendish genius: the cause is being represented as a cure! The Japanese may indeed be dragged back in.

Note Opening paragraph of (Iwanaga, Kashiwagi, Arayama, Fujioka & Hashimoto, 2013) in the original

1971年に出された全国教育研究所連盟の報告書(1を契機として,「落ちこぼれ」という言葉が新聞で報道され,社会問題化したことに象徴的に現れているように,1970年代以降,わが国においては教育問題が顕在化することになる.その後,少年非行,校内暴力,器物破損,怠学へと問題は拡散し,80年代には金属バットによる両親殺害事件,浮浪者襲撃事件など青少年犯罪の凶悪化が問題視され,家庭内暴力,いじめ問題が,そして90年代にはいると不登校の急増,高校の中途退学問題,連続的に起こった青少年の殺人事件など,教育問題は深刻さを増していく

Bibliography

Iwanaga, S., Kashiwagi, T., Arayama, A., Fujioka Y., & Hashimoto, H. 岩永定, 柏木智子, 芝山明義, 藤岡泰子, & 橋本洋治. (2013). 子どもの自己肯定意識の実態とその規定要因に関する研究. Retrieved from reposit.lib.kumamoto-

Yourou T. 養老孟司. (2003). バカの壁. 新潮社. Retrieved from 218.219.153.210/jsk02/jsk03_toshin_v1.pdf

Image bottom

お祓い串 by Una Pan, on Flickr

Labels: autoscopy, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, psychology, religion, reversal, self, sex, Shinto, specular, 宗教, 日本文化, 自己, 自己視

Thursday, March 26, 2015

City Views and the Horror of Impartial Spectation

This video shows the the view over Yamaguchi City from Elephant Head Mountain at the entrance to Oouchi Mihori area of Yamaguchi City. You can climb this mountain from the rear of Toushiro Tea Shop opposite Yellow Hat and Uniqlo in Oouchi Mihori, or from the rear of Itukushima Shrine next to Shinwaniishibashi junction with the four legged pedestrian overpass. There car parks the beginning of both paths. The path from the shrine is wooded and natural. The path from behind the tea shop is made of concrete.

In this video I argue that Japanese people tend to avoid places with good panoramic views since they associate them with the divine which, in the Japanese case, visually spectates rather than listens. The Japanese simulate birds eye views of themselves and their situations in their minds but since this Other is that which allows them to have a self they also hide from themselves that they are doing this 'impartial spectating' (Smith, 1759). As a result of which, while the Japanese are happy and inclined to create imaginative artworks, such as pictures of the floating world and childrens' paintings, from the point of view of the birds eye view (Masuda, Gonzalez, Kwan, & Nisbett, 2008), the Japanese do not actually want to go there, to the dreaded viewing platform.

Often times Japanese are even unaware that viewpoints exist in reality. One of my colleagues was of the opinion that there is nowhere from where our town could be viewed, but in addition to this viewing platform, I live on a mountain or hill of 118m, which taller than the viewing platform shown in this video, at a mere 85m, right in the centre of Yamaguchi City overlooking both the older part of the city and the Hot Spa area. The under-utilization of Japanese viewpoints represents a tremendous potential tourism industry.

The the birds eye viewpoint is an abject place, a terrifying location that should not exist since it always exists as hidden simulation. In Japanese Horror monstresses (a neologism I use because generally Japanese monsters are female) often hang out on ceilings, looking down, or emerge from mirrors and other images. They also hang out on mountain tops as mountain aunties (yamanba).

There should be a Western equivalent of this phenomenon "Nacalianly" transformed from the visual into the linguistic. As a Westerner I should have a horror of "going" to the place where I can 'impartially' hear myself speak, the equivalent of the Japanese birds eye view. But, logophonic "places" are not really "places," but discursive 'viewpoints' or logical 'positions' (ronten 論点 not shiten 視点), so I was (until I am writing this now) confused as to where the "real" equivalent of the "impartial spectator" that I simulate in my mind might be situated in the world. Where is the linguistic version of a mountain top? Where am I scared to go?

I hypothesize now that the place that I am scared of visiting is "the text," or a particular type of text that is addressed to no one in particular. I can write a blog, here, since I imagine that I am speaking to someone, that this burogu is a dialogue with a real other. But as soon as I attempt to write, objectively, for publication, I face "The Problem of the Text" (Bakhtin, 1986) and the absence of a dialogical other and must confront -- or not confront by not writing -- my super-addressee: a monster in my mind. In fact, as I attempt to write, I often find myself going to look at visual views, especially that from the balcony at the end of my fourth floor corridor at Yamaguchi University, perhaps in order to escape *the horror of linguistic impartial spectation*.

This realisation may make it easier for me to write. Perhaps I should write on top of mountains.

Viewing platform in Google Earth

https://goo.gl/maps/SocFV

Viewing platform in Google Maps

https://goo.gl/maps/SqQXt

Bibliography

Bakhtin, M. (1986). The Problem of the Text in Linguistics, Philology, and the Human Sciences: An Experiment in Philosophical Analysis. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays, 103-31.

Masuda, T., Gonzalez, R., Kwan, L., & Nisbett, R. E. (2008). Culture and aesthetic preference: Comparing the attention to context of East Asians and Americans. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(9), 1260-1275.

Smith, A. (1759). Theory of Moral Sentiments. Retrieved 2015/03/26 from http://www.ibiblio.org/ml/libri/s/SmithA_MoralSentiments_p.pdf

Labels: autoscopy, japan, japanese culture, Nacalian, theory, 日本文化, 自己視, 観光

Monday, March 23, 2015

Curved Jewels as (Internal) Ears

Children and adults can make curved jewels at the Yoshinogari museum of ancient Japanese culture in Saga (吉野ヶ里歴史公園) for about 2USD a jewel. My children enjoyed making one each this weekend.

Curved jewels (magatama) are one of the few things mentioned in Japanese mythology that are also found in reality.

As 'transitional object' in both myth and reality, they form one of the three sacred items symbolic of the Japanese imperial lineage the other two being a mirror, of the Sun Goddess, and the sword, that was found inside the tail of a multi-headed snake.

In Japanese mythology, the Sun Goddess is wearing a necklace of curved jewels when she meets her brother Susano who takes some of these jewels, puts them into his mouth, chews (onomatopoeically "kami-kami") them to bits and spits them out into the 'central well of heaven' to create other gods (kami) and imperial ancestors.

This act continues the Japanese mythological theme of "creation via dripping" often onto a reflective surface. The creative act of chewing symbols and spitting them out onto a mirror making the noise of what one is making ("kami" or deities), struck me as being a pagan expression of creation via the word - we speak to internalised other in the mirror of our mind, thereby making the world, speciated, en-wordified.

In Japanese mythology this act of creation, however, ends in disaster. Susano commits all manner of "sins" and his sister the Sun Goddess is lost to the world, since she hides in her cave. When the sun goddess has hidden in her cave, Amenouzume (lit "the headdress wearing woman of heaven) the founder of Japanese masked theatre (and I believe Susano in drag) wears a special headdress including curved jewels, to encourage the sun goddess to come back out of her cave by performing an erotic dance on top of a drum which made all present laugh, which encourages the Sun Goddess to come out of her cave again.

[My interpretation is that this is Susano attempting to return from the hell of the narrative self, by enacting it as an erotic solo, transsexual, auditory - hence the drum - dance to achieve enlightenment through satire and humour. Derrida represents the tragedy in a book of self addressed loving, erotic postcards. Japanese mythology and dance is more behavioural. ]

The curved jewels are said to have first have been made by deity by the name of "Parent of the Jewels" whose shrine is about 20 km from where I live in Yamaguchi Prefecture near Hōfu City (Tamanooya Jinja 玉祖神社).

This brings me to the occurrence of curved jewels in reality. They are found widely in ancient Japanese Joumon (lit. "string pattern" [pottery]) archaeological sites and in ancient burial mounds and in ancient archaeological royal sites from Korea.

The Japanese claim that the curved jewels spread from Japan to Korea, whereas Koreans claim that they spread from Korea to Japan. In Korea they are called gogok or comma shaped jewels and are found paired with mirrors on the regalia of Korean Kings in decidedly ear shaped forms, hanging from a tree shaped crown (similar that worn by Ameno-Uzume, the head-dress-woman, my "Sunsano in drag").

The fact that they hang from a tree has suggested that they represent a fruit.

[A fruit reminds me of Adam's apple, which gets stuck in our throat. I would also be inclined to suggest that the tree crown may also have had a practical purposes as a primitive "selfie-stick" to enable its wearer to see himself reflected, and echoed, in mirrors and jewels, there dangling.]

There are several other theories as to the significance of the shape of curved or comma jewels, all of the following from Wikipedia.

The shape of an animal tusk

The shape of the moon

The shape of a two or three part tomoe (as represented in the above image top row)

The shape of the moon

The shape of the soul

The shape of ear decorations

I had liked the part tomoe (Taoist and Shinto symbol) interpretation, for no good reason, but the ear decoration theory is more persuasive.

According to recent research (Suzuki, 2006) on curved jewels unearthed in Korea and Japan, curved jewels are found alongside "nearly circular ear jewellery split into two halves. The visual evidence for ear jewellery as the origin of curved jewels appears to be strong (see the above link and bottom left in the above image).

This interpretation does not conflict with the tomoe or soul interpretation. Various scholars (Mead, Bakhtin, Freud, Lacan, Derrida) claim that the self is dependent upon the assumption of an ear into the psyche. As such, a fitting together (either as a circle or tomoe) ear-shaped or ear-associated jewel may have represented a transitional, partial-self-object.

It is known that mirrors were given to others as remembrance tokens or keepsakes by the ancient Japanese from poems in the Book of Ten Thousand Leaves (manyoushuu). Looking at a mirror presented by a loved one, one might feel their gaze. Hearing the sound of the clinking of a curved jewel, made from the earring of ones mother or girlfriend, one might imagine the attention of their loving ear.

I have also claimed that headless deformed Venus figurines, including ancient Japanese dogu and and ancient Jewish Ishtar idols, may have represented the represented part of an autoscopic visual self. 'The ancients' may have known more about the parts from which the self is created, or at least been more fully aware that the self is created from parts. Moderns may have become more prudish, and lost our sense of humour.

In Japanese mythology, when Susano chewed the Sun Goddesses' curved jewels and spat them out into a reflective surface (in which he may have been reflected as his sister, I claim), she took his sword and chewed it and spat it out likewise into the well of heaven. The curved jewels therefore form a pair with swords. In a myth parallel to that in which the sword (Kusanagi no Tsurugi) was found in the tail of a snake, the sword is associated with the naming of its owner. Indeed it could be argued that the sword that Susano finds in the snake is his symbolic self-representation. If jewels represent internalised ears, then it would be appropriate that they be paired with swords as self symbols or names. Mirrors can represent the perspective/gaze, and the transitional, part-self image that is gazed at, and the world-heart in which it takes place.

It seems to me that my self-narrative and any internal ear take place on or in the mirror of my consciousness which sees as it is seen.

In China, "nearly circular" earrings (I thought that they were "butt" shaped earrings in an earlier version of this post!) are sometimes represented as a snake or dragon biting its own tail. Out out damn butt (! I jest, ketsu, 玦) snake! My self narrative is gay.

That in Japan the "incomplete circle" 玦 "pig dragon" earrings are broken into two, and worn as necklaces seems to me to represent the way in which language and the linguistic self in Japan does not form an "incomplete circle," completed by the reality of the ear or face, nor go around in Japanese people's minds but is broken. The linguistic self, the "I" of the cogito, is in Japan, as Mori claims, broken, a "you for you."

Under this reading, the myths of Susano - with his sister and in Izumo - are about how one form of selfing defeated another: in Japan the paradoxical circle of light defeated the incomplete snake circle of speaking. Or paraphrasing the myth from Guam, some humans managed to escape from hell to live in the light of the sun, without physically or imaginatively nailing themselves to a tree.

Perhaps I should dress up in drag and dance in front of a mirror. I did in fact recommend dancing in front of a mirror to a schizophrenic many years ago. That patient showed remarkable but only temporary improvement.

Images

http://shiga-bunkazai.jp/%E8%AA%BF%E6%9F%BB%E5%93%A1%E3%81%AE%E3%81%8A%E3%81%99%E3%81%99%E3%82%81%E3%81%AE%E9%80%B8%E5%93%81%E3%80%80no-84/

Suzuki, K. 鈴木克彦 (2006) "縄文勾玉の起源に関する考証."『玉文化』3号.

Labels: autoscopy, cultural psychology, culture, image, japan, japanese culture, Jaques Lacan, mirror, religion, 宗教, 文化心理学, 日本文化, 自己, 自己視

Thursday, March 19, 2015

Provide all the Accoutrements of a Temple

This is a bell at Two Lovers Point in Guam. The management of this most popular iconic spot on the resort island of Guam are at least subconsciously aware that if you want Japanese tourists to come to your destination, then provide them with all the accoutrements of a pagan temple: a legend, something symbolic ideally natural, some good luck charms (locks), a place to leave votive offerings (the rails to leave love locks), a way of making non-linguistic noise either by clapping, or ideally by a bell (as pictured above), and an opportunity for autoscopy: a mirror or place to take a selfie. Tourism is secular pilgrimage.

Labels: autoscopy, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, tourism, 日本文化, 自己視

Wednesday, March 18, 2015

Japanese Try Harder When they Fail

As demonstrated by Heine et al.,'s famed experiment, (2001) the Japanese try harder when they fail, whereas Americans try harder when they succeed.

This is explained upon the theorisation that the important thing for North Americans is to feel good about themselves, so they try hard when they succeed, whereas the important thing for Japanese is to feel appreciated and socially included so they try hard when they fail. I remain highly impressed by this research and have been teaching its conclusions in my cultural psychology classes for the past several years.

But upon reflection, the former explanation regarding North Americans is more persuasive than the latter regarding Japanese. Groups express gratitude as much as they sanction so why should it be that Japanese try harder when they fail?

Another possible explanation might be due to the fact that the task was a linguistic one - a word game. North Americans are obsessed with word games, and expect themselves to be good at them. Japanese however, do not expect themselves to be good at word games and would be less likely to feel bad about having failed at the task. What would have happened if the task was to create something in folded paper, or some sort of visual manipulation task?

This question relates to the other main theoretical thrust of the paper in question: the assertion that Japanese believe themselves and their performance, to be tractable to effort, whereas North Americans believe themselves to have intrinsic aptitudes and abilities that are not tractable to effort. Thus North Americans attempt to find the areas in which they themselves and only themselves excel, and avoid those areas where they fail, whereas Japanese are more inclined to believe that given the right environment (the right club, the right coach, the right incentive) anyone can achieve anything if they put themselves in the right environment and try hard.

I believe that Heine's theory conforms to an extent to the facts. Yes, Japanese are more inclined to believe in the power of effort and whereas yes, Americans are more inclined to believe in the importance of aptitude.

I am aware that the third experiment in the same paper tested whether manipulation of the these self views effect performance. Japanese and American subjects were told that their performance would, or would not, vary according to effort, or conversely that performance was, or was not, related to aptitude. It was found that, in the failure condition, telling Japanese that the task was tractable to effort changed their effort little, whereas telling North Americans that the task was tractable to effort changed and enhanced their performance a lot. It was argued that therefore, Japanese chronically presume their performance to be dependent upon effort (so being told that "effort work"s had little effect) whereas Americans when told that effort is effective, tried harder.

[I have tried the reverse manipulation in the success situation with non-significant but Heine predict result among Japanese. Japanese were told that that they had succeeded at a word game - thinking up positive adjectives and then being told that the average student can only think of x adjectives where x is less than the true mean. One third of the subjects were told that the task was about ability (才能) a third were told that the task was tractable to effort and a third were told nothing. I then left the room, saying that I had to get another survey and told them that they could write some more positive adjectives if they like below the line signifying those that they had written with the test time. The group that were told that the task was about ability wrote more extra words that those in the other conditions but not significantly. Having an American mindset, about words at least, makes Japanese try harder in success situations whereas having a Japanese mindset makes Americans rebound better in failure situations.]

But what if the task itself were culturally dependent? Is it that Japanese believe themselves to malleable, and North Americans believe themselves to be a product of their aptitudes as Heine argues?

Or could it be that with regard to word games (the task) North Americans believe themselves, as narrative selves, to be intractable to effort, whereas Japanese who see word games as irrelevant, believe that effort works?

The cultural attitude towards effort and aptitude was also tested, in experiment 4 or 5 of the same paper, finding North Americans to far more inclined to believe in aptitude, and Japanese far more inclined to believe in effort. However the tasks (that I can remember) were ability in History and piano playing, both rather 'logo-phono-centric.' If it is true that North Americans and Westerners in general believe themselves to be self narratives, whereas Japanese do not, then narratival ability -- definitely history, perhaps music -- may be seen to be aptitude based by North Americans and Westerners.

If however Japanese believe themselves to be autoscopically apprehended corporealities then visual tasks might be believed to be more aptitude based.

This, my hypothesis, is fraught. Even very visual, corporeal activities, such as baseball, are believed to be very tractable to effort in Japan.

At the same time, I continue to believe that the "centre of gravity" of the Japanese self may be visual, and that of Westerners narratival, so the belief in effort-changeable malleability, or conversely in aptitude, may depend upon the conception of self, and the nature of the task.

AND, oh dear, these considerations lead me to question the nature of 'identity' across time and space. Narratives exist in time, vision exist in space. Hence anyone believing in a visual self or a narratival self would be likely to believe in differing amounts of 'malleability' in the spacial and temporal dimensions.