Wednesday, December 28, 2016

How Unnverving is Conformance?

The American social news media site, Digg says that this video is unnerving. I guess that is because Westerners do not like conformance. On the other hand, the majority of Japanese comments on YouTube below the video are positive. This could be due to the prevalence of individualism vs collectivism and to an extent I would agree but, according to me, it is because Westerners lack individuality and must strive for difference lest they mind-meld, whereas Japanese are loaded with quirkiness -- as is clearly Professor Ikeguchi, the inventor -- and admire those individuals and metronomes that strive towards harmony.

See for example Masaki Yuki's research (Yuki, Brewer & Takemura, 2005) on Japanese and American groups for proof.

同調は不気味でしょうか。

ディッグというソーシャルニュースサイトによれば、このビデオは不気味です。同調するものが好きではないからでしょうかな。下記日本人のコメントは主に肯定的です。個人主義 対 集団主義で解釈されそうですが、それもありでしょうが、欧米人は個性が不足しているから努力して反発しなければ考えが同化してしまいそうですが、池口先生を初め、日本人は逆に個性に富むので協和に励む人間(やメトロノーム)を肯定的に思うというのは持論です。

結城雅樹(Yuki, Brewer & Takemura, 2005)の米国と日本の集団のあり方についての実証的研究をご参照ください。

Yuki, M., Maddux, W. W., Brewer, M. B., & Takemura, K. (2005). Cross-cultural differences in relationship-and group-based trust. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1), 48-62. Retrieved from http://kokoro.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/cultureko_net/pdf/Yuki_et_al_2005PSPB.pdf

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japanese culture, 個人主義, 文化心理学, 日本文化, 集団主義

Sunday, October 09, 2016

Misunderstood Japan

Someone asked on Quora what do foreigners misunderstand about Japan. I answered as I always do that Foreingers at least since Ruth Benedict (1946) think that Japanese shame is external, imposed on them from the outside, when in fact the Japanese live in the sight of the Sun God, Amaterasu, or Otendou-sama (Funahashi, 2008) who watches from within their hearts.

This explains why for instance, the Japanese do tidy up not only football stadia (even when their national team loses) but also tidy up in the privacy of their hotel rooms (Funahashi, 2008, p.166) and toilet cubicles which they leave as if unused, contra non-Japanese guests.

Conversely it is because Japanese care about how things look from a special perspective in their hearts, NOT from the point of view of other people, which is the reason why Japanese cities are a bristling, bubbling morass of individuality as opposed to rows of houses all looking the same.

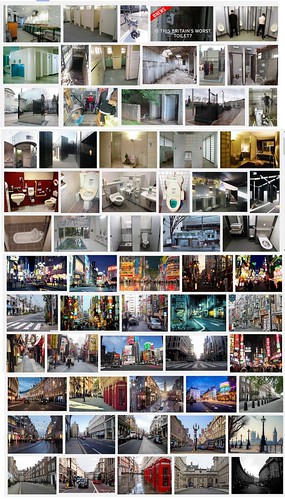

The above images are the Google image search results, at half size, for:

I Top) British public toilet inside

2) Japan public toilet inside

3) Tokyo Street

4) London Street

お取り下げご希望でありましたら、下記のコメント欄かnihonbunka.comのメールリンクからご一筆ください。Should anyone want me to cease and desist please send me a note via the comments or to the mail link at nihonbunka.com

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japanese, japanese culture, nihonbunka, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Thursday, February 11, 2016

Sassure via Maruyama Explains Yuki's Group Types

Labels: blogger, collectivism, culturalpsychology, Flickr, groups, individualism, japaneseculture, Nacalian

Wednesday, May 27, 2015

Comparative Morality and The Horrible Helper

In the USA when a child found some money (admittedly not inside a wallet) he was lauded for giving it to someone else.

Handing the money into lost property did not seem to cross anyone's mind in the USA.

Western commentators since the Edo period have marvelled at Japanese honesty with regard to personal possessions and the absence of theft. They also marvelled at the sexual mores (nakedness and the prevalence of prostitution), and speech crime (e.g. flattery, deceit, and creative accounting). That said I believe the Japanese to be the most moral nation on earth.

"The Lost Letter Technique" made famous by Milligram et. al. (1965) found that 70% of personally address letters but only 25 of Nazi/Communist party addressed "lost letters" were returned. Earlier research by Merritt and Fowler (1948: see Liggett, Blair, & Kennison, 2010) found that 85% of letters, but only 54% of letters presumed to contain money were returned.

And yes, there is comparative Lost Letter Technique research. West (2003) dropped phones and wallets containing cash in Tokyo and New York and the results were T 95% vs NY 77% for phones and T 85% vs NY30% for cash. That makes Tokyoites about three times more honest when it comes to returning wallets. Near Tokyo rates of return were obtained outside a Japanese supermarket in New York, so this is not something geographical. The Japanese are extremely honest when it comes to personal property.

In Japan stealing is almost absent, but creative accounting and linguistic obfuscation is reported to be prevalent. In the historical record numerous commentators report the low level of stealing (Bird, 1880; Cocks & Thompson, 2010; Coleridge, 1872; Golovnin, Rīkord, & Shishkov, 1824) and the strict way in which it is dealt with. At the same time, visitors have noted that linguistic misdemeanour's such as flattery, deceit, and "the squeeze" (taking a kickback of up to 100% to 200% of cost: see Bird 1880).

I claim, as always, that the amazing way in which the Japanese do not steal things but are at the same time able to "squeeze" double or triple the expenses from their employer relates to the nature of the Other (and horror) in Japanese culture.

Westerners have a horrible other that listens. This encourages us to be fairly honest, if very self-serving, in our self-narrative. Our narratives are self-enhancing but are constrained by the need for them to be palatable to another imagined human being. On the other hand, we feel no one is watching, so how we look, however, is far less fraught, ego-involved. We can get very fat, or even justify theft as redistribution of wealth (Robin Hood), since "property is [or can be argued, narrated to be] theft." We are good at promises and institutions of linguistic trust (such as insurance, and financial products) since we want to be heard to be, narrated to be, good.

The Japanese, on the other hand, have an Other (that is almost as horrifying) that looks, concealed not in the head but amongst the crowd. This encourages them to be fairly upstanding, if very self-serving, in their posture (sekentei). Their self-imaginings are self-enhancing but are constrained by the need for them to be palatable to another imagined human being. So the Japanese abhor crimes and misdemeanour's that can be seen, such as theft and physical violence. When it comes to linguistic malfeasance such as "the squeeze" or kick-back however, this can be seen as just a way of doing business involving no visual injury. The Japanese are good at creating things (monozukiri) since they want to be seen, imagined to be, good.

This modal -- language vs vision -- difference highlights one aspect of the origin of the myths of individualism and collectivism. It is not in fact the case that the Japanese are any more or less individualistic or collectivist, nor Westerners likewise. Both Japanese and Westerners care to an extent about real others and care more about their horrible intra psychic familiars, but in each case the horror of the familiar must be hidden.

It is only because our familiars, our imaginary friends, are horrible that they can remain hidden and continue to be familiar. Identity is a contradiction that depends upon horror, or sin, on a split that must be felt to be, but not be cognised as being. Identity or self is impossible (nothing can see or say itself) but the dream of its possibility is maintained by desire for, and abhorrence -- and resultant obfuscation -- of the duality required.

In the Western case the necessary, horrible imaginary friend is hidden *inside* the person as an interlocutor that, as inside the person, can only therefore be denied by being claimed to be part of, and one with the self. Eve, that gross "knowing" helper we have, is hidden by virtue of being thought of as just another me (see Levinas vs Derrida and "altrui"). She disappears because, as Adam Smith says, we are just splitting ourselves into two of ourselves. If there is just me and me, then there appears to be nothing disgusting going on. Westerners think, "I think to myself."

But if on the other hand the Other is external, as is required by any visual (self) cognition, there is little way of claiming that the Other is me. Spatial dualism, or rather distance, eye and surface, as required by visual cognition, becomes apparent, and undeniable. So the Japanese claim that all they are doing is being collectivist. The Japanese horrible Other is just another person, one of many other people. The Japanese hide the horror, their familiar, their imaginary friend, in the crowd.

Individualism and collectivism are myths by which means we hide Eve/Amaterasu, a part of our souls, our "helpmeets"or "paraclete" (John's term for Jesus).

In a similar way to paradox of Japanese morality in which Japanese will not steal your wallet even if you leave it on a table at a restaurant and walk out, but may (or did) charge a kickback doubling or tripling the price, the British will be utterly polite, honest and even humorous as they sell you narcotics and destroy your country, as we did to China for 150 years. Some estimate that the enforced import of opium into China resulted in the deaths of 100 million Chinese, but at least one British academic makes jokes about it .

Paraphrasing Isaiah, those that worship the logos have a tendency to smear over their eyes so that they cannot see, and those that worship idols have a tendency to smear over their hearts so they cannot comprehend.

Bibliography (all available online)

Bird, I. L. (1880). Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: An Account of Travels in the Interior Including Visits to the Aborigines of Yezo and the Shrines of Nikkô and Isé. J. Murray.

Cocks, R., & Thompson, E. M. (2010). Diary of Richard Cocks, Cape-Merchant in the English Factory in Japan, 1615–1622: With Correspondence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coleridge, H. J. (1872). The life and letters of St. Francis Xavier : in two volumes. Asian Educational Services.

Golovnin, V. M., Rīkord, P. Ī., & Shishkov, A. S. (1824). Memoirs of a Captivity in Japan, During the Years 1811, 1812, and 1813: With Observations on the Country and the People. H. Colburn and Company.

Liggett, L., Blair, C., & Kennison, S. (2010). Measuring gender differences in attitudes using the lost-letter technique. Journal of Scientific Psychology, 16–24. Retrieved from http://www.psyencelab.com/images/Measuring_Gender_Differences_in_Attitudes_Using_the_Lost-Letter_Technique.pdf

Milgram, S., Mann, L., & Harter, S. (n.d.). The lost-letter technique: A tool of social research. Retrieved from http://www.communicationcache.com/uploads/1/0/8/8/10887248/the_lost-letter_technique-_a_tool_of_social_research.pdf

West, M. D. (2003). Losers: recovering lost property in Japan and the United States. Law & Society Review, 37(2), 369–424. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1540-5893.3702007/full

Labels: autoscopy, collectivism, individualism, japanese, japanese culture, Nacalian, nihonbunka, reversal, sex, 日本文化

Friday, April 24, 2015

Do Foreigners make more Gestures?

It is a common perception in Japan that non Japanese make more and more exaggerated gestures while talk to each other than Japanese. This excerpt from a comic (Oguri, 2010, p.8) on the differences between a Japanese woman and her foreign husband includes the copy "Well of course foreigners have much more exaggerated gestures, as we all know."

On the other hand, Western perception of Japanese gestures is mixed. On the one hand there is a perception that the Japanese wear for instance a "mask of inscrutability" and are covered "beneath courteous reserve" (Craigie, 2004, p. 172). In Japan "people have to suppress their true feelings practically all the time" (Rice, 2004, p144).

At the other extreme, caricatures of Japanese such as in the Directors Cut of Grand Blue where a Japanese diving coach works his diver so hard the later feints, or Isuro "Kamikazi" Tanaka played by Takaaki Ishibashi "who helps excite the team" with his frantic overwrought gestures in Major League 2. Japanese gestures can appear exaggerated to Westerners too. Part of the reason for both Japanese and Westerners thinking that the other's gestures are exagerrated is likely due to the fact that the gestures themselves are different, and phenomena to which one is not accustomed stand out.

Surprising though it may seem to Japanese, research on nodding beat gestures (Maynard, 1987: see also Kita, 2009) generated during speech production, showed that Japanese approximately four times more nods, once ever 5.57 seconds whereas Americans nod only every 22.5 seconds (informal study, Maynard, 1987, p602, note 4). Both Japanese and Americans nod at the beats, and baton touch turn-taking position. But Japanese nod, not only at these times and in the back channel, but also in the middle of their own statements.

So who does make more gestures. A quick comparison of a couple of wedding speakers in Japanese in English on Youtube demonstrates the source of this difference. Americans wave their hands more and use obvious exaggerated, semi iconic facial gestures (like those caricatured above) more liberally but Japanese use a great deal of nodding and bowing to emphasise what their are saying, demonstrate sincerity and as beats. No wonder Japanese speakers get "shoulder ache" (katakori). Conclusive research on the relative importance of gesture remains to be done.

The Japanese, like Italians, also have a wide lexicon of iconic gestures that can be used in place of speech. And as always, I argue that Japan is NOT a high context culture (Hall, 1966; Honna, 1988: see Tsuda, 1992) but that visual communication is the central media and in Japan language is considered to be part of the context. This means that language will often be used to express flattery and other pleasantries (tatemae, such saying "I'll think about it") in stead of "no". Whereas the true meaning (honne) is expressed in the face, posture, pause and expression. Returning to Major League 2, for all his exaggeration, famed Japanese comedian Takaaki' Ishibashi's caricature of the Japanese is faithful. His expressions move from one form to the next like a Kabuki actor, or Kyari Pamyu Pamyu, nothing is left to chance, there is in Barthes' words "perfect domination of the codes" (1989, p.10)

The closest that a Western scholar gets to recognising that gesture and the non-verbal could be central to self and meaning in Japan is Roland Barthes' "Empire of Signs" (1983) (based in part on the observations of Maurice Pinguet).

Now it happens that in this country (Japan) the empire of signifiers is so immense, so in excess of speech, that the exchange of signs retains of a fascinating richness, mobility, and subtlety, despite the opacity of the language, sometimes even as a consequence of that opacity. The reason for this is that in Japan the body exists, acts, shows itself, give itself, without hysteria, without narcissism, but according to a pure - though subtly discontinuous - erotic project. It is not the voice (with which we identify the "rights" of the person) which communicates (communicates what? our-necessarily beautiful-soul? our sincerity? our prestige?) but the whole, body (eyes, smile, hair, gestures, clothing) which sustains with you a son of babble that the perfect domination of the codes strips of all regressive, infantile character. To make a date (by gestures, drawings on paper, proper names) may take an hour, but during that hour, fur a message which would. be abolished in an instant if it were to be spoken (simultaneously quite essential and quite insignificant), it is the other's entire body which has been known, savoured, received, and which has displayed (to no real purpose) its own narrative, its own text. (Barthes, 1983, p.10)

Barthes comes close. He can't help making a "text" of the Japanese body, the only way that he can admit it has meaning since in his hierarchy only language can truly mean (see Barthes, diagram p. 113).

Barthes famously claims that "the centre (of Japan, the Japanese subject) is empty," and in the above passage that its communication has "no real purpose," but at the same time Japan has forced him to question the purpose of his own vocalisations. And he is wrong that the body talk is erotic. He is talking to and about himself. Japanese signs and selves are cute. The relative absence of words, and the erotic beguiled him to conclude that the centre of Japan is empty. The self and centre of Japan does not have or needs words, but is is far from empty rather visual and raging, fury Kyari Pamyu Pamyu barfing eyeballs full.

Finally, while Merbihain's 93% (Mehrabian & Ferris, 1967) has been rejected even by Mehrabian (Mehrabian, 1995: see Lapakko, 1997) it is clear that non-verbal communication is extremely important. Bearing this in mind the pressing question for me is how Hall (1976) had the gall (!) to claim that those cultures that do not see language as central to human communication are "high context" at all? That nonverbal communication is contextual assumes that language is central, privileged when in fact in Japan, it is often the reverse.

Taking one example, Hall claims that in Japan people expect more of others.

"It is very seldom in Japan that someone will correct you or explain things to you. You are supposed to know and they get quite upset when you don’t. ... People raised in high context cultures expect more of others than to the participants in low-context systems. When talking about something that they have on their minds, a high context individual will expect his interlocutor to know what is bothering him, so that he doesn't have to be specific." (Hall, 1976, p98)

Do Westerners really expect less of others?

I find that in interaction with Japanese I often expect them to have heard my words, the generalities that I have stated, and to apply them across multiple situations. I expect this of them. When I bothered about some situation where previously expressed verbal wishes and requirements are not being met, I expect others to know and get quite upset (like a arrogant fool) when they don't. Americans expect others to understand their generalities - their linguistic expressions - as Japanese expect others to look, mirror and behave appropriate to the situation. This is due to the fact that the central mode of meaning is different not because members of either culture place greater or lesser expectations upon others.

Dumping the hierarchy of the old Western text/context word/world dualism will help us to understand the Japanese and ourselves.

Bibliography

Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies. (A. Lavers, Trans.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Barthes, R. (1983). Empire of Signs. (R. Howard, Trans.). Hill and Wang.

Craigie, R. (2004). Behind the Japanese Mask: A British Ambassador in Japan, 1937-1942. Routledge.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond Culture. Anchor Press.

Kita, S. (2009). Cross-cultural variation of speech-accompanying gesture: A review. Language and Cognitive Processes, 24(2), 145–167. doi.org/10.1080/01690960802586188

Knapp, M., Hall, J., & Horgan, T. (2013). Nonverbal Communication in Human Interaction. Cengage Learning.

Lapakko, D. (1997). Three cheers for language: A closer examination of a widely cited study of nonverbal communication. Communication Education, 46(1), 63–67. Retrieved from www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03634529709379073

Maynard, S. K. (1987). Interactional functions of a nonverbal sign Head movement in japanese dyadic casual conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 11(5), 589–606. doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(87)90181-0

Mehrabian, A., & Ferris, S. R. (1967). Inference of attitudes from nonverbal communication in two channels. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 31(3), 248. Retrieved from psycnet.apa.org/journals/ccp/31/3/248/

Oguri, S. (2010). Dārin wa gaikokujin.

Rice, J. (2004). Behind the Japanese mask--: how to understand the Japanese culture-- and work successfully with it. Oxford: HowToBooks.

Labels: collectivism, culture, image, individualism, japan, japanese, japanese culture, 日本文化, 自己視

Friday, April 03, 2015

For the first time, I'd like myself to praise myself: But I can't

The modality of self-ing is the one in which reflexivity, such as self-praise, appears to entail no contradiction or duality.

On that day nearly 20 years ago, Yuko Arimori did not praise herself. Perhaps she was aware she could not. She only expressed the desire to do so.

From a Japanese socio-linguistic point of view (Mori, 1999), to be able to praise herself Ms. Arimori would have needed to have become two people.

This is why she used her, now famous phrase "For the first time, I want myself to praise myself ." Hajimete, jibun de jibun wo hometai to omoimasu. 初めて自分で自分をほめたいと思います

Ms. Arimori writes she borrowed the phrase from the poem of a folk singer and marathon runner as explained here in Japanese but in fact her version retains the duality (myself twice, "jibun de jibun wo"), expressed in the original only by the fact that it is addressed to the song's listener "you."

Arimori could no more praise herself than Westerners can see themselves without the aid of a mirror. A duality is required. The Nacalian transformation of Arimori's statement is Narcissus's gaze but that is not to say that Ms. Arimori is a narcissist - far from it. Both express the impossibility of self reference on ones own. And yet, Westerners praise themselves, and Japanese can see themselves without any apparent contradiction.

Mori, A. 森有正. (1999). 森有正エッセー集成〈5〉. 筑摩書房.

The original version of Ms. Arimori's explanation is here

有森 あの言葉を最初に聞いたのは高校のときです。私は高校の三年間ずっと都道府県駅伝で補欠でした。その開会式に高石ともやさんがこられて、読まれた詩にあった言葉です。それを聞いて感極まるものがあって大泣きしたんですよ。

アトランタの練習中、ネガティブになっていたとき、クルーのだれかに「自分で自分をいいと思えばいいじゃないか」といわれて、ふっとその言葉を思い出し たんですね。でもそのときは、「いや、いまは自分で納得できない、ここで自分をほめたら弱くなる、するんだったらレースの後にしたい」と思いました。

I first heard those words when I was a high school student. For the three years of my high school I had always been the reserve team member for the prefectural long distance relay (ekiden). The Tomoya Takaishi (folk singer and runner) came to the opening ceremony, and the phrase was in a poem that he read. I was so moved by his words that I burst into tears. Then, when I was in training for the Atlanta Olympics, and became negative, when one of the crew said "If you think you are okay, then that'll do won't it?" I remembered Tomoya Takaishi's words. But then, I thought, "No, not now. It wouldn't fit. If I praised myself now, I'd get weaker. If I am going to praise myself, I'd like to do it after the race."

The song is here.

Earlier version:

On the occasion winning of her second Olympic marathon medal, a bronze medal at the Atlanta Olympics, Arimori Yuko famously said "I want for the first time to praise myself" before bowing her head in defiance, shame and tears,. Ripples of shock rang out through the Japanese nation.

To a Westerner it is a marvel that this might be the first time she praised herself, and a mystery as to why she might wish to bow, bashfully (?) and cry afterwards. But in Japan the soundbite became famous and even controversial. This is because in Japan it is rare, and not cool to praise oneself. Generally, and in Arimori's case in Barcelona, Japanese sports persons even or especially when they are winners solely praise other people (see the first half of the same video for evidence).

For example the postwar Japanese philosopher, Susumu Iribe (Kobayashi & Irebe, 2004, p42) who believes in linguistic nature of the self and (lacking a linguistic Other) the dependence of the individual upon the socius, criticized Arimori's words as indicating that she was happy just for herself, when he feels that she should have been running for the good of the nation.

In my opinion Japanese sports persons do run for themselves as well as for their nation, but there is something preventing them saying so -- a block to linguistic self-praise. This taboo is parallel, I believe, to the Western rejection of "narcissism" a term which particularly applies to be people who are infatuated with how they look like the hero of the eponymous myth. In either case the resistance to self praise or love in each media is because that media is not perceived to be self, and as such, it involves a duality.

This distinction between enjoying how you look and self-praise may explain the gap between boasting and flattery in Japan. The Japanese are big on flattery, use it liberally and seem even to enjoy it a little. From a Western point of view, anyone vain enough to enjoy flattery would also be likely to indulge in self-praise. But this is not the case. Japanese, like Arimori praise (and perhaps flatter) others liberally, but praise themselves only once in a lifetime. How can this be explained?

If how one looks matters then flattery praises that visual aspect of the self. Self praise on the other hand, praises the narrative subject .

Why can't Japanese linguistically praise their own self-image? I think that to do so would be to introduce a gap between themselves as acting, praising subject, and their self-image, which they generally regard as themselves, except in exceptional circumstances.

This event was one such circumstance. In both occasions when Arimori praises herself there is a duality, a self-to-self gap. In the second more famous instance she does not simply praise herself, as a Western sportsperson might, but used the now famous "For the first time, I want myself to praise myself ." Hajimete, jibun de jibun wo hometai to omoimasu. 初めて自分で自分をほめたいと思います。

In the same interview, three minutes earlier however, the interviewer had suggested it must have been tough running after on her heel, after her recent heel operation. Fending off the interviewer's attempt at flattery, Arimori responded (in what was in fact, her first self/heel praise) "Rather than think about the operation and all that, I was really pleased and grateful to [my heel which] had carried me all this way, and to the start line at the Olympics." Arimori's first self praise (of her heel) in the original was

Kakato no shujutsu no koto yori, koko made sasaete moraeta koto ga sugoto ureshikatta"踵の手術のことより、ここまでささえもらえたことがすごくうれしかった。

Whether Arimori's disembodied state of mind was encouraged simply by the interviewers question, or not I do not know, but I think that at the end of a long hard race, while being videoed on national television, Ms. Arimori was in an unusually disembodied state of mind, which enabled her to praise first her heel, and then a little later herself, "for the first time".

Conversely perhaps, Westerners are in a chronically disembodied state of mind which makes it easier for them to praise themselves.

Image of Yuuko Arimori from 9:03 in this video used without permission.

お取下げご希望でありましたら、下記のコメント欄、またはnihonbunka.comまでご連絡ください。

Bibliography

小林よしのり、西部邁. (2004). 本日の雑談, Volume 4. 飛鳥新社

Labels: autoscopy, collectivism, culture, image, individualism, japanese culture, nihonbunka, 日本文化

Thursday, April 02, 2015

Almost No Show of Hands in Japan

The founder of the Panasonic corporation claimed that the reason why putting things to a vote was unpopular in Japan, and the emphasis on consensus, is not because the Japanese are sheep who feel the need to move in a heard, but conversely there are always so many big egos that would be offended if their faction lost the vote (Tanisawa, 1995, p60). Vote made visible, by a show of hands or by standing up, are only very rarely used, and never in any Japanese committee meeting that I have attended. To lose, and lose visibly in this way would be for the Japanese extra specially painful and ego-damaging because the Japanese are who they see themselves to be.

パナソニック株式会社の創業者・松下幸之助は、欧米人と比較して日本人の方は自尊心があまりにも高いとする稀な見解を示した。松下によれば、欧米と違って民主主義的な多数決が日本人に馴染まない理由は、「全員の自尊心を満足させなければならない。自尊心が日本人ほど強いと、多数決は絶対に成立しない」(谷沢永一, 1995, p60)。ましてや、挙手投票や起立投票は私が参加した日本の会議では使われたことがない。自分が自分を見る存在は自分自身ですので、目に見えてまけるというのは特に痛くて「顔がつぶれる」と感じられるであろう。

Image

MEPs vote by show of hands by European Parliament, on Flickr

谷沢永一. (1995). 松下幸之助の智恵. PHP研究所.

Labels: collectivism, image, individualism, japanese culture, 日本文化

Wednesday, August 06, 2014

Not quite yet a Visual Turn

Is cultural psychology at last taking a visual turn? Yes, and at the same time, not quite. There is the 'theory of Dov Cohen' which integrated the notion of the visual other into the main "collectivist" interpretation of Japanese culture based upon, imho, a misunderstanding of the consequences of a generalised other.

The highly interesting and thorough research of Uskul and Kikutani (2014) appears to follow this Co-hen-ian ;-; trend demonstrating that taking a third person perspective on ones self is related to public self awarenes, motivating actions that are social but not those that are private.

And yet, mirrors -- the easiest way of promoting a third person perspective on self -- are found to promote private self awareness, and the tendency to reject social expectations. Mirrors provide another type of generalised other, and another type of individuality not heightened collectivism.

Who is right? This research (Uskul & Kikutani, 2014) presents hard data, demonstrating the connection between third person perspectives and motivation to conform to social expecations.

Perhaps the problem is the "person." In my opinion, the Japanese do not have a third person perspective, but see themselves from eye of their god (generalised other, super ego, Other, (m)other, superadressee, impartial spectator). The generalised, impartial, super, unconscious, de-personalised nature of the Other (verbal or visual) is the key to making a "god", and commcomitant (verbal or visual) self.

But basically I am all washed up. Kind professor Steven Heine already gave me some work. Perhaps, in the words of the late great Satoshi Kon, when I am starving I can ask for some more work, but by then they may ask "he was a Co(-author w)hen?"

Sorry.

写真お取り下げご希望でありましたら、ご連絡ください。Please contact me if you would like me to remove your photos, taken from your homepages via the comments or email link at nihonbunka.com

Uskul, A. K., & Kikutani, M. (2014). Concerns about losing face moderate the effect of visual perspective on health-related intentions and behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. works.bepress.com/ayse_uskul/31

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japanese culture, Jaques Lacan, Nacalian, nihonbunka, reversal, specular, theory, 日本文化, 集団主義

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

Don't Do It: Preventing Suicide East and West

Self-awareness occurs in different modalities. Sometimes people engage in self-touching when feeling shy (Edelmann et al., 1989), and drink copious amounts of fluids thus becoming pneumatically aware of their digestive tract when suffering from psychosis (see: de Leon, Verghese, Tracy, Josiassen, & Simpson, 1994)*. But generally speaking, human self-awareness takes places in two channels or modalities: through language and though vision.

Typically, in Western literature the former, linguistic self awareness is privileged. Mead, the father of social psychology, argues that speech necessarily demands of speakers to hear themselves from the point of view of their listeners (plural), giving rise to the 'generalized other' (Mead, 1967), 'super-addressee' (Bakhtin,1986), 'Other' (Lacan, 2007), and 'impartial spectator' (Smith, 1812). Typically Western theorists argue, by application of common sense I presume, that in order to see oneself however, one needs a mirror. Mead writes "If we exclude vocal gestures, it is only by the use of the mirror that one could reach the position where he responds to his own gestures as other people respond" (Mead, 1967, p.66).

However, the recent discovery of 'mirror neurons' (Iacoboni, 2009a, 2009b) , the concomitant neural capability of 'autoscopy' (Blanke & Metzinger, 2009; Metzinger, 2009) and our own work demonstrating that the Japanese, but not North Americans, have "mirrors in their heads," (Heine, Takemoto, Moskalenko, Lasaleta, & Henrich, 2008) demonstrates that Mead's common sense assumptions about human inability to see themselves without a mirror is incorrect. Humans, especially if properly trained through the Japanese arts (Zeami; see Yusa, 1987; Ozawa, 2006) can activate their mirror neurons and hone their ability to learn to see themselves, just as Westerners can and do develop their debating skills and hone their ability to hear themselves from others' and then, importantly, the Other's objective point of view.

Cultures differ in the predominance of each type of self awareness. As we have seen, the Japanese have an ability and proclivity to be aware of themselves visually. This is demonstrated likewise by the tremendously positive way in which they portray themselves visually with their poses, fashion, and automatically corrected "puri-kura." That Americans are predominantly aware of themselves in the linguistic domain is, even if one does not believe theorists such as Mead (1967), Bruner, Lacan (2007), Hermans and Kempen (1993), Ricoeur (1990), Derrida(2011), McAdams, Bakhtin (1986)** to name but a few, adequately demonstrated by the way in which they have a strong and robust desire for positive linguistic self regard. All the studies showing positive self regard on the part of North Americans and and equivalent lack on the part of Japanese, for instance, are linguistic. The only studies to demonstrate a greater or equivalent positivity among Asians are visual: auto-photography (Leuers = Takémoto see Mukoyama, 2010, Ch.1), collage (Leuers = Takémoto & Sonoda, 2000), briefly presented flash cards (Yamaguchi et al., 2007), and positivity in recollection of photos.

What happens when the non-culturally preferred medium of self-awareness is promoted?

Among Westerners it has long been known that, unless they are feeling in a good mood, Mirrors tend to promote a novel mode of self-awareness making them aware of failure to meet social norms (Heine, Takemoto, Moskalenko, Lasaleta, & Henrich, 2008; Sedikides, 1992). The negative impact of mirrors is all the more pronounced when Westerners are in a state of negative affect. It is hardly surprising therefore that, as demonstrated by recent research (Selimbegović & Chatard, 2013), mirrors increases thoughts of suicide among Westerners. And, yet, mirrors are used as a means of preventing suicide in Japan (Oshimi, 1992).

After more than two decades of economic stagnation, the level of suicide in Japan has reached historic highs. One way in which Japanese railway authorities have found effective in reducing the level of suicide by jumping in front of passing trains is to install mirrors on platforms. Mirrors are the culturally familiar mode of self-awareness in which the Japanese have learnt to self enhance. To see themselves as loved, lovable, even cute. Remembering the internalised gazes of their loved ones, the Japanese look at the mirror, see the side of themselves that they still love, don't do it and go home.

The equivalent stimulus for increasing positive self regard among Westerners has long been known - provide them with a telephone, a listening ear, and an opportunity to narrate themselves. Hearing ones self speak is enough to put your average Western, but not East Asians (Butler, Lee, & Gross, 2007, 2009; Butler, 2012), in a better, not a worse, mood.

As recent research (Selimbegović & Chatard, 2013) indicates, increase in the incidence of suicide might arise however if mirrors were situated on the Golden Gate Bridge, or I suggest, if suicidal Japanese were encouraged to narrate themselves***. This last possibility does not seem to be one which Japanese medical health professionals, even Mukoyama (2010), seem to have considered.

The image above is from the Wikipedia page on Infamous Suicide Spots, showing the suicide prevention mirror on the the platform of Ogikubo Station's Central Line, and a "Crisis Councelling" telephone on Sanfransisco's Golden Gate Bridge.

Inspired in the first instance by (Selimbegović & Chatard, 2013)

Bibliography

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. (V. W. McGee, Trans., C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Eds.) (Second Printing.). University of Texas Press.

Blanke, O., & Metzinger, T. (2009). Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(1), 7–13. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.10.003

Butler, E. A. (2012). Emotion Regulation in Cultural Context: Implications for Wellness and Illness. In S. Barnow & N. Balkir (Eds.), Cultural Variations in Psychopathology: From Research to Practice. Hogrefe & Huber Pub. Retrieved from www.hogrefe.com/program/media/flyingbooks/600434/files/as...

Butler, E. A., Lee, T. L., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion, 7(1), 30.

Butler, E. A., Lee, T. L., & Gross, J. J. (2009). Does Expressing Your Emotions Raise or Lower Your Blood Pressure?: The Answer Depends on Cultural Context. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(3), 510–517. doi:10.1177/0022022109332845

Derrida, J. (2011). Voice and Phenomenon: Introduction to the Problem of the Sign in Husserl’s Phenomenology. Northwestern Univ Pr.

Hermans, H. J. M., & Kempen, H. J. G. (1993). The Dialogical Self: Meaning as Movement. Academic Press.

Heine, S. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 879–887. Retrieved from www2.psych.ubc.ca/~heine/docs/2008Mirrors.pdf

Iacoboni, M. (2009a). Imitation, Empathy, and Mirror Neurons. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 653–670. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163604

Iacoboni, M. (2009b). Mirroring people: the science of empathy and how we connect with others. New York, N.Y.: Picador.

Lacan, J. (2007). Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English. (B. Fink, Trans.) (1st ed.). W W Norton & Co Inc.

Leuers = Takémoto, T. R. S., & Sonoda, N. (2000, November). 心像的自己に関する比較文化的研究(6) -メディア(言語とイメージ)の違いと日米比較― Cross Cultural Research on the Specular Self: Differences in Media (Language and Image) and comparison between Japan and America. Oral Presentation口頭発表 presented at the The 64th Annual Convention of the Japanese Psychologiocal Association English日本心理学第64回大会, Kyoto University. Retrieved from nihonbunka.com/docs/shinzoutekijiko6.docx

Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist (Vol. 1). The University of Chicago Press.Metzinger, T. (2009). The Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self (1st ed.). Basic Books.

Mukuyama, Y. 向山泰代. (2010). 自叙写真法による自己認知の測定に関する研究. ナカニシヤ出版.

Oshimi, T. 押見輝男. (1992). 自分を見つめる自分: 自己フォーカスの社会心理学.

Ozawa, T. 小沢隆. (2006). 武道の心理学入門: 武道教育と無意識の世界. 東京: BABジャパン出版局.

Sedikides, C. (1992). Attentional effects on mood are moderated by chronic self-conception valence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(5), 580–584. Retrieved from psp.sagepub.com/content/18/5/580.short

Ricoeur, P. (1990). Time and Narrative. (K. Blamey, Trans.) (Reprint.). Univ of Chicago Pr (T). Selimbegović, L., & Chatard, A. (2013). The mirror effect: Self-awareness alone increases suicide thought accessibility. Consciousness and cognition, 22(3), 756-764.

Smith, A. (1812). The theory of moral sentiments. Retrieved from books.google.co.jp/books?hl=en&lr=&id=d-UUAAAAQAA...

Yamaguchi, S., Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., Murakami, F., Chen, D., Shiomura, K., … Krendl, A. (2007). Apparent universality of positive implicit self-esteem. Psychological Science, 18(6), 498.

Yusa, M. (1987). Riken no Ken. Zeami’s Theory of Acting and Theatrical Appreciation. Monumenta Nipponica, 42(3), 331–345. Retrieved from myweb.facstaff.wwu.edu/yusa/docs/riken.pdf

Notes

* This is the way I (and perhaps Derrida) see self speech, as a sort of self touching, self-comforting, auto 'hostipitality.'

**I know that I am ignoring Cooley and Goffman. It seems to me that the latter, and those that base there analyses on Goffman's approach such as McVeigh (Wearing Ideology) come closest to the position that this blog espouses but, in Goffman's and McVeigh's case at least it seems to me that their dramatological, 'looking glass self" is 'presentational.' That is to say that the Goffman and McVeigh (if not the Cooley) 'looking glass self" is an image of me for you, for another specific other. And this is the nub of the matter. The Japanese too hear their self speech from the ear of otherS but they lack the "generalized" (Mead, 1967), "super" (Bakhtin, 1986) Other (Lacan, 2006) and they have, and we lack, a generalized gaze of the world.

*** Based on Western practice, the Japanese have taken to situating telephones at suicide spots. It seems possible to me that a telephone to the Japanese is a bit like a mirror to Westerners. A telephone encourages people to narrate themselves, and in Japan that, among those that have debt, interpersonal problems, encourages them to narrate themselves negatively in the absence of Eve, a generalized other, super-addressee, or ear that loves them. I know that there is some (though very little) OSA research that uses voice, but I suggest that a telephone is a Nacalianly transformed mirror.

Labels: individualism, japan, japanese culture, Nacalian, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, reversal, 日本文化

Wednesday, October 09, 2013

Capsule Hotel: Groupist or Individualist?

The thought of Japanese salaried employees getting into the their capsules and sleeping in air-conditioned pods like larvae in a hive may give the impression of the psychology of the herd, mindless groupism. On the other hand it may be an example of social atomism (Allison, 2006), and even individualism since, in a Western country, this scene -- like that of the ubiquitous Japanese student accommodation, "one room mansions" -- might be replaced by a that of a more friendly, communal dorm. Or the capsule hotel may be an example of social estrangement and collectivism since, like the prevalence of social withdrawal (hikikomori) and social phobia (taijinkyoufusho), it may be the result of as a result of greater social dependence (amae: See Doi, 2002), a concomitant inability to leave immediate family, (Kato et al., 2012) and as therefore demonstrating the lack of a developed, independent self.

My own feeling is that neither categorisation is particularly useful and that each are mutually dependent - the self is social - (Markus & Kitayama, 1991) but that Westerners tend to use this dichotomy due to the influence of Christianity, the main text of which is a series of vignettes where the hero ignores social and follows his conscience. The possibility that "conscience" is also social is generally refuted or ignored.

Allison, A. (2006). New-Age Fetishes, Monsters, and Friends: Pokêmon Capitalism at the Millennium. Ed. Tomiko Yoda and Harry D. Harootunian. Japan after Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present. Durham & London: Duke UP, 331–57.

Doi, T. (2002). The Anatomy of Dependence. Kodansha USA.

Kato, T. A., Tateno, M., Shinfuku, N., Fujisawa, D., Teo, A. R., Sartorius, N., … Kanba, S. (2012). Does the ‘hikikomori’ syndrome of social withdrawal exist outside Japan? A preliminary international investigation. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(7), 1061–1075. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0411-7

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review; Psychological Review, 98(2), 224. Retrieved from www.biu.ac.il/PS/docs/diesendruck/2.pdf

Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist (Vol. 1). The University of Chicago Press.

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Tuesday, July 02, 2013

Japanese Fashion in the Mirror of the Heart

See Taro in the middle of a circle of his friends. The Japanese self is often described as being relational (Watsuji, Bendedict, Markus, Hamaguchi) which boils down to it being non-existent, or at best a nexus of self presentation concerns. The Japanese self is in the eye of the other, we are told.

If this were all there were to the Japanese self then how could the Japanese create and wear the zaniest fashion in the world? If this were the case, then if Taro dyed his hair blonde and wore blue contact lenses to college (picture 2), he would feel the harsh, judgemental gaze of his peers and become embarrassed (picture 3).

How could he avoid embarrassment? How could he remind himself of his preference for blonde hair and blue eyes? He could whip out his mirror (picture 4). As demonstrated by Carver ( 1975) and Carver & Scheier (2001) people with increased "objective self awareness" in front of mirrors, remain truer to their beliefs even in the face of social pressure. The trouble is, with all those eyes upon him, Taro would need to walk around looking in his mirror all the time.

But Taro has no need to do his, because Taro and all Japanese, especially those who have practised some kind of martial art or traditional path, has a mirror in his head (Heine, Takemoto, Moskalenko, Lasaleta, & Henrich, 2008). Taro can see himself without the aid of a mirror, avow his preference for blonde hair and blue eyes, and be done with the eyes of the world (picture 5).

It is because they have a mirror in their heart - originally a present from the Sun Goddess we are told - that the Japanese make the zaniest fashion in the world.

All five images based on an original by Miho Fujimura.

Carver, C. S. (1975). Physical aggression as a function of objective self-awareness and attitudes toward punishment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11(6), 510–519. Retrieved from www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0022103175900025

Carver, Charles S., & Scheier, M. F. (2001). On the Self-Regulation of Behavior. Cambridge University Press.

Heine, S. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 879–887. Retrieved from www2.psych.ubc.ca/~heine/docs/2008Mirrors.pdf

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japan, japanese culture, mirror, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, religion, specular, 個人主義, 宗教, 日本文化, 武道, 神道, 集団主義

Thursday, June 27, 2013

Intergroup Comparison versus Intragroup Relationships

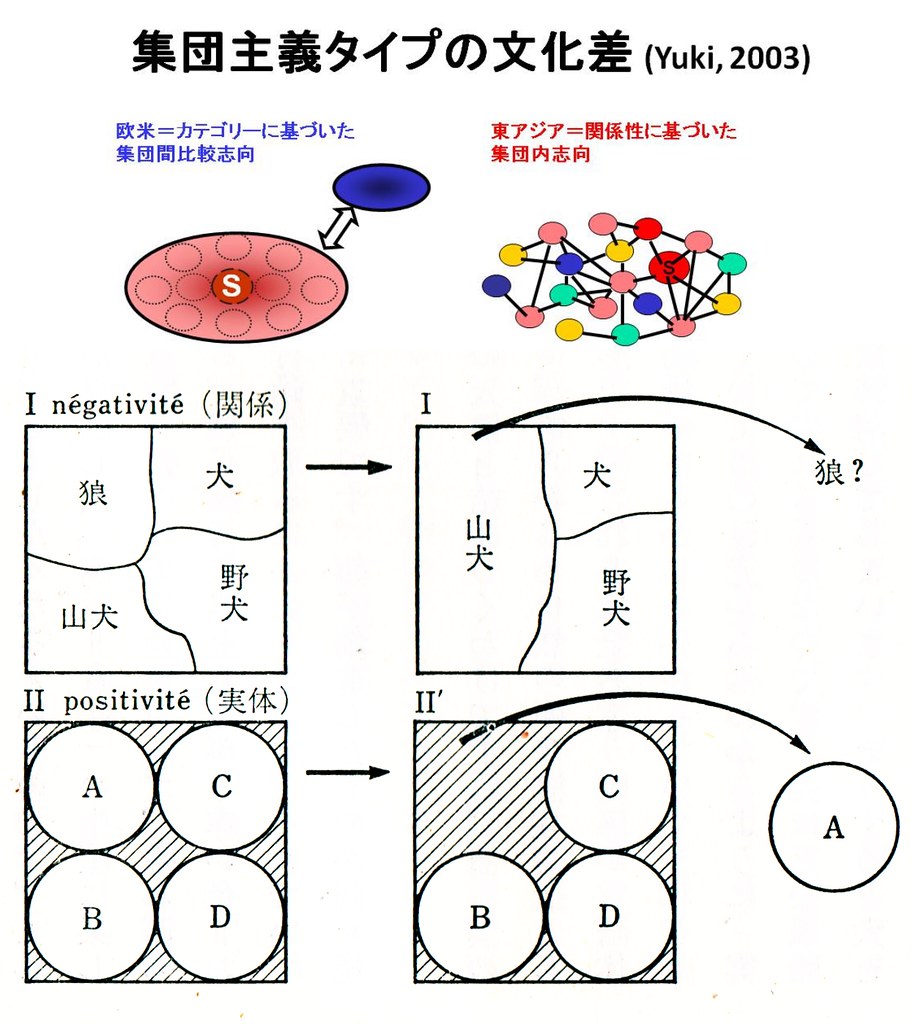

The image above, adapted from Yuki (2003, p172) , shows how Americans and Japanese conceive of groups. Westerners concentrate on the name and set of central attributes of that group and all members feel themselves to share that attribute with all other members, in comparison with outgroups and their members who do not share the same attributes. These can be quite simple such as soccer fans may see membership of their teams fan base as derived from their belief that they "Want Chelse/Liverpool to win." They may chant "Chelsea, Chelsea," or "Liverpool, Liverpool," and they may mind merge with the social identity of their group becoming an outgroup hating herd animal. They do this to achieve vicarious self-enhancement through identification with the presumed superiority of their group. Their team wins, and the fans bask in reflected glory. Even if they loose they can believe that the fans are the most "loyal." And either way they can engage in an ego trip believing their group and/equals themselves to be superiority to others. Western group members therefore indulge in intergroup comparison, to enhance beliefs of the form "we are better than them" and "they are worse than us." This herd-like comparative group cognition is illustrated in the top diagram (a).

Japanese on the other hand pay attention to the many and various relationships and the network of relationships *within* their group. They have no interest in making downward comparison to the detriment of other groups. Their groups do not need a scapegoat, an other, to form at all. They are bonded by mutual cooperation, by "give and take" (a loan-expression from English into Japanese), obligation (giri) and ninjou (empathy) towards ingroup members. Rather than compare, they concentrate on maintaining ingroup harmony. Since the name of Japanese group game is cooperation, the individuality of the group members, their many and various talents that they can bring to the mix, are valued rather than ignored. So there is no moronic mind-merge, no hooligan herd, for the Japanese it would seem.

I love this theory and there is a lot of evidence to support it. Westerners are more likely to positively evaluate and be chummy with those that they are similar to (Heine, Foster, & Spina, 2009; Schug, Yuki, Horikawa, & Takemura, 2009), and more likely to remember information regarding inter-group rather than intra-group relationships (Takemura, Yuki, & Ohtsubo, 2010), whereas are more likely to trust someone in the same relationship network as themselves, rather than merely due to the fact of belonging to some nominal group (Yuki, Maddux, Brewer, & Takemura, 2005).

And as I have written before the emphasis for me is upon "nominal." Westerners like myself tend to conceive of others, their groups and themselves linguistically - in the latter case as having some shared characteristics. Whereas Japanese tend to conceive of groups in their imagination which results (as Lacan argues) in groups being conceived in terms of a network of binary relationships.

However, it occurred to me this morning, based upon the above argument, the group of "Americans" should also be that much more mind-merged, herdlike and amalgamous people - believing in common shared characteristics* - whereas the Japanese as a group, should, in so far as they understand themselves as a group at all, be bristling with individuals all cooperating together for the sake of synergy but never, for the sake of the same synergy, becoming the same. The motto of the Japanese group is, the words of Confuscious "harmonise not herd!" (和して同せず).

Thus in a culture with so great a respect for individuality, such as Japan under Yuki's theory, it is not surprising that "harmony" should be heralded and aspired towards. Likewise in a culture with so much mind-mulching, herdery, it is not surprising that individualism be that towards which its members are encouraged to aspire.

Does that satisfy? I think that I have gone a little too far and suggest a slight amendment to diagram (b) above. Yuki probably only drew the relationships as external to the group members in order to draw attention to them. He makes it entirely clear that intra-group attention is based upon the Interdependent model (Markus and Kitayama, 1991, diagram page 226) or in Kasulis (2010, diagram p 225) which provides philosophic, the relationships are shown interior to the selves. Implied by Yuki's analysis, I suggest therefore diagram (c) as a modification to diagram (b). Under this conception, the Japanese cease to be so radically individual, as compared to Americans, since they are aware that their individuality is fostered, created and maintained by virtue of their relationships with others which are self-forming and interpenetrate and overlap with the self.

How is this even possible? How can other person really be part of oneself? If that other person and your relationship is conceived in the visio-imaginary, then as Nishida (see Heisig, 2010) and Mach (1897), argue, it takes place in a place which is, paradoxically, both oneself and the world.

*The American Mantra: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

Heine, S. J., Foster, J.-A. B., & Spina, R. (2009). Do birds of a feather universally flock together? Cultural variation in the similarity-attraction effect. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 12(4), 247–258. Retrieved from onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2009.0128...

Heisig, J. W. (2010). Nishida’s Deodorized Basho and the Scent of Zeami’s Flower. In Frontiers of Japanese Philosophy 7: Classical Japanese Philosophy (pp. 247–73). Nagoya: Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. Retrieved from nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/staff/jheisig/pdf/Nishida%20and%20Zea...

Kasulis, T. P. (2010). Helping Western Readers Understand Japanese Philosophy. Dialogue, (34). Retrieved from nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/2124

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review; Psychological Review, 98(2), 224. Retrieved from www.biu.ac.il/PS/docs/diesendruck/2.pdf

Schug, J., Yuki, M., Horikawa, H., & Takemura, K. (2009). Similarity attraction and actually selecting similar others: How cross-societal differences in relational mobility affect interpersonal similarity in Japan and the USA. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 12(2), 95–103.

Takemura, K., Yuki, M., & Ohtsubo, Y. (2010). Attending inside or outside: A Japanese–US comparison of spontaneous memory of group information. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13(4), 303–307. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2010.01327.x

Yuki, M. (2003). Intergroup comparison versus intragroup relationships: A cross-cultural examination of social identity theory in North American and East Asian cultural contexts. Social Psychology Quarterly, 166–183. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/1519846.pdf

Yuki, Masaki, Maddux, W. W., Brewer, M. B., & Takemura, K. (2005). Cross-cultural differences in relationship-and group-based trust. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1), 48–62. Retrieved from psp.sagepub.com/content/31/1/48.short

Labels: collectivism, culture, image, individualism, japan, japanese culture, logos, Nacalian, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

The Invasion of Customized Goods Vs Masaki Yukism

Social and Cultural Psychologist Masaki Yuki, after a spell at Professor Marilynn Brewer 's (presumably Ohio State) university in the US was amazed at the extent to which Americans are proud of and merge with their groups, at least to the extent to which US university students wear university sweat shirts bearing the name of their own institution, and come the day of the university American football game, half the campus would come to the match dressed in the same, university colours, chanting the team name.

As professor Brewer argues, Americans join groups to gain a desirable social identity, as a member of a of a presumed elite with which they merge. Badges and uniforms of membership that enhance the group-individual mind meld, are thus desirable, as are negative evaluations of rival groups. "We are good and/because they are baaad."

The Japanese on the other hand are far more economic in their group membership, preferring to join groups in which they can cooperate to form a unity greater than the sum of its parts. The important thing is the network of exchange relationships between the individuals who physically enhance each other's welling through the synthesis of different skills and aptitudes. Group member uniformity is thus avoided and Japanese group members do not see other groups as rivals, paying little attention to them at all.

While there is a bit of Westernisation going on at my university, and there is a mini invasion of the self-snatching, clone-ware, customised goods, Yuki's cultural psychological theory is probably my favourite (after my own) since it has something qualitative to say about the Japanese side of the cultural equation. In most of the other great cultural theories, Japan is typified by a lack or absence: lack of a internal moral standard (Benedict), lack of individuality (Hofestede), lack of illusion of individuality (Markus and Kitayama), lack of a need for positive self-regard (Heine), lack of linguistic thought (Kim), lack of focus (Masuda and Nisbett).

This post in video: the film of the burogu. Bibliography

Yuki, M. (2003). Intergroup comparison versus intragroup relationships: A cross-cultural examination of social identity theory in North American and East Asian cultural contexts. Social Psychology Quarterly, 166–183. lynx.let.hokudai.ac.jp/COE21/workingpaper/no04abstract.pdf

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

The Chinese are Japanese Too

Subjects, looking at the front (left) of the shelves is faced with a choice (A) of moving the block on the left up, or (B) the block on the right up. But if they think about it, they should be aware that the "instructor" can not see the darker block on their right, and must therefore mean the block on the left. American (and no doubt British) subjects are often too dumb to work this out!

Chinese are not so dumb. They almost never move the wrong block because they look at the shelves from the point of view of the "instructor." In other words, the researcher point out, the Chinese are good at "perspective taking". They are able to see things from an auto-focused or autoscopic perspective. The Chinese, like Kyari Pamyu Pamyu and Japanese martial artists, can look at themselves from the position of the world, as if they have extra eyes pointed inwards towards themselves.

Scholars such as Iacoboni (2009) and Metzinger (2009) show us that all humans can see themselves, take out of body perspectives (Blanke & Metzinger, 2009) but from the above research it is clear some cultures can see themselves more clearly.

This ability to see from autoscopic perspectives pointed towards oneself, as if equipped with a freely positionable mental mirror (Heine, Takemoto, Moskalenko, Lasaleta, & Henrich, 2008) is the defining characteristic of Japanese culture. It represents a different type of "perspective taking" to that refereed to by Mead (1967) since it is not carried out in language. It does, like Meadian linguistic perspective taking result in a sense of self and it may be encouraged by choreographed, repetitive (see Butler, 1993), set-behaviours (kata and dance routines) that through their performance turn the body into a sign and encourages the performer to see these signs from the point of view of the other, and to establish an auto-focused gaze.

This culture of the eye of the other, is due in part to the influence of the Shinto religion, the primary deity of which sees herself as, refers to herself as, and is represented as, a mirror. This mirror is said, by at least one Japanese religious leader (Kurozumi, 2000), to be in the heart of the Japanese.

The experimental evidence points to it being found in the hearts of Chinese too. The first mirrors that were treated with reverence in Japan were imported from China so it is probably fair to say that this ability, to take external auto-focused perspectives, is as Chinese as it is Japanese. I have no doubt that it is engendered as much by Taichi (太極拳) as it is by Karate, or Kyari's dancing. The Chinese and Japanese need to realise their similarities and learn to be friends.

Lower image copyright Kyari Pamyu Pamyu (きゃりーぱみゅぱみゅ) the director Jun Tajima, and Warner Music Japan.

Blanke, O., & Metzinger, T. (2009). Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(1), 7–13. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.10.003

Butler, J. (1993). Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of "Sex. Routledge.

Heine, S. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 879–887. Retrieved from www2.psych.ubc.ca/~heine/docs/2008Mirrors.pdf

Iacoboni, M. (2009). Imitation, Empathy, and Mirror Neurons. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 653–670. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163604

Kurozumi, M. (2000). The Living Way: Stories of Kurozumi Munetada, a Shinto Founder. (W. Stoesz & S. Kamiya, Trans.). Altamira Pr.

Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist (Vol. 1). The University of Chicago Press.

Metzinger, T. (2009). The Ego Tunnel: The Science of the Mind and the Myth of the Self (1st ed.). Basic Books.

Wu, S., & Keysar, B. (2007). The effect of culture on perspective taking. Psychological science, 18(7), 600–606. Retrieved from pss.sagepub.com/content/18/7/600.short

Labels: autoscopy, eye, image, individualism, japan, japanese culture, mirror, Nacalian, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, Shinto, specular, 日本文化, 神道, 自己視

Thursday, November 08, 2012

The Face of Pachinko and the Illusion of Control by True-Grit

This series of films Pachipro Naniwa Ryouzanpaku 1-6 (1996-1998) stars Hiroyuki Watanabe playing the leader of a "professional" pachinko playing group. A gambling group by this name really existed. The name comes from a Chinese legend meaning a place where skilled, aficionado outlaws congregate. The Hole in the Wall meets Fu Man Chu.

Essentially all that Mr. Watanabe's character does is shoot little balls up into a hole. As you can see from his expression, however, Watanabe's character has true grit, guts, or balls, and can put them all out on the table and play to very last one.

The film series also builds on a group motif. The pachinko professionals fight as a team. I would not be surprised if those that are addicted to pachinko believe that they have the uncommon ability, uncommon konjo, to lay it all on the line for those they love, even as they waste their family finances pumping the pachinko machine.

The type of control that pachinko players hold the illusion of having, is almost as Morling (Morling, 2000; Morling & Epstein, 1997; Morling & Evered, 2006, 2007; Morling & Fiske, 1999) describes. Rather than actively changing their environment, the Japanese change or even rather negate the self, but throught doing so they wait out the storm and come through on the other side as, they delude themselves, winners.

I think that the Japanese may be engaging in true-grit-ism (konjoushugi, 根性主義; Yamagishi, 1979) a method of achieving external outcomes through self-control, rather than self-control for its own sake or harmony. No matter how much it may seem that Japanese aerobics is harmoniously self-controlling, it also achieves its stated environmental objective (Morling, 2000) of loosing weight. From the pachinko hall to the sumo stables (heya) and judo club (dojo) one can see Japanese engagining in collective self-denial, but I think that in all cases they have their eyes on the prize. Japanese self negation is not just collectivism, but a means to a personal end.

In any event, I hypothesise that gambling and problem gambling among Japanese will therefore correlate more with true-grit-ism (konjoushugi, 根性主義; Yamagishi, 1979) than illusions of (primary) control, for which scales exist (Moore & Ohtsuka, 1999; Raylu & Oei, 2004).

Possible Items for a True-Grit-ism(根性主義) scale taken from Yamagishi's paper (1979) above (English translations and some revision to the original Japanese are mine).

目標を速成するためには、禁欲すなわち己に克つことが最も大切である。

In order to achieve ones goals abstinence -- being able to achieve a victory over oneself -- is the most important thing.

目標を速成するためには、努力と精神力が大切である。

In order to achieve your goals, endurance and mental strenght are important.

忍耐と持続力、そして自己犠牲の精神があって、義務の遂行すれれば、目標を達成できる。

You will achieve your goals if you carry out your duties with endurance, the power to continue, and a spirit of self-sacrifice.

努力し、苦労すれば、幸福になることができる。

If you endure and toil you can achieve happiness.

幸福を得るためには、強い精神力が必要である。

In order to be happy you need to have a strong spirit.

持続性、つまり同じことを繰り返し行なうことにより人間形成がなされる。

One can grow as a person by persisting - doing the same thing over and over again. 自己犠牲の精神を発揮することにより人間形成がなされる。 One can grow a person through the application of the spirit of self-sacrifice.

精神力すなわち欲望を断ち切り己に克つことのできる力こそが大切なものである。

The most important strength to have is strength of sprit: the strenght to defeat ones desire, and achieve victory even over oneself.

精神力でオリンピックの金メダルを獲得することができる

You can win an olympic goald medal through strength of mind.

Under Langer's formulation those that have "an illusion of control" are those that suffer from the illusion that there is an easy way, a free lunch, a short cut to riches, that gamble. I suggest that in Japan it is precisely the opposite sort of people - those that believe that perseverence can get you anywhere - who end up in front of the pachinko machine. In that sense pachinko hits the best of us. I think that something should be done.

Bibliography

Heine, S. J. (2003). An exploration of cultural variation in self-enhancing and self-improving motivations. Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 49, pp. 101–128). Retrieved from http://www2.psych.ubc.ca/~heine/docs/nebraska.rtf

Langer, E. J. (1975). The illusion of control. Journal of personality and social psychology, 32(2), 311. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/psp/32/2/311/

Moore, S. M., & Ohtsuka, K. (1999). Beliefs about control over gambling among young people, and their relation to problem gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 13(4), 339. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/adb/13/4/339/

Morling, B. (2000). ‘Taking’ an Aerobics Class in the US and ‘Entering’ an Aerobics Class in Japan: Primary and Secondary Control in a Fitness Context. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 73–85.

Morling, B., & Epstein, S. (1997). Compromises produced by the dialectic between self-verification and self-enhancement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(6), 1268.

Morling, B., & Evered, S. (2006). Secondary control reviewed and defined. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 269.

Morling, B., & Evered, S. (2007). The construct formerly known as secondary control: Reply to Skinner (2007).

Morling, B., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). Defining and measuring harmony control. Journal of Research in Personality, 33(4), 379–414.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2004). The Gambling Related Cognitions Scale (GRCS): Development, confirmatory factor validation and psychometric properties. Addiction, 99(6), 757–769. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00753.x/full

Yamagishi, T. 山岸俊男. (1979). 根性主義-『おれについてこい!』 の内容分析. 一橋論叢, 81(2), 181–197. Retrieved from http://hermes-ir.lib.hit-u.ac.jp/rs/handle/10086/13228

The images are copyright their creators: "Pachipuro Naniwa Ryouzanpaku" (1996-1998) directed by Monna Katuso, starring Watabe HIroyuki, Ozawa Kazuyoshi, Yanagisawa Chou, Ishitsuka Hidehiko and Ishibashi Mamoru, based on a Manga by Hamada Fumio and Go Rikiya. Distributed by KSS 門奈克雄監督(1996-1998)『パチプロ浪花梁山泊(1-6)』。渡辺裕之、小沢和義、柳沢 超、石塚英彦、石橋 保 ほか主演。脚本(漫画)浜田 文太、 郷 力也 (1996)『パチプロ浪花梁山泊』。ケイエスエス

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Wednesday, November 07, 2012

The Effect of Social Support on Americans and Japanese

I like this paper and consider it relevant to those in the hospitality industry. When I first came to Japan, being a Westerner of low self-esteem, I did not like the way that Japanese hospitality providers would provide me with English language menus, forks or disposable chopsticks, since I felt that their kindness was saying, "you can't read Japanese," "you can't use ordinary chopsticks." I felt their kindness was an attack upon my self-esteem and independence. So, beware of helping Westerners. Some of them, are hinekureteiru or twisted.

At the same time, if the Japanese tendency to try to help prior to any demand (sasshi) is explained first, Japanese style hospitality, such as that provided by traditional inns (ryokan) providing luxury but choice-less food (kaiseki) with mothering helpers (nakai) can be a very rich cultural experience.

Bibliography

Uchida, Y., Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., Reyes, J. A. S., & Morling, B. (2008). Is Perceived Emotional Support Beneficial? Well-Being and Health in Independent and Interdependent Cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(6), 741–754. doi:10.1177/0146167208315157 Retrieved from faculty.washington.edu/janleu/Courses/Cultural%20Psycholo...

Labels: care-givers, collectivism, individualism, japanese culture, nihonbunka, tourism, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Sunday, November 04, 2012

Cultures Amazing Consequences

It is so thick and so expensive that perhaps few people read Hofestede's incredibly famous "Culture's Consequences" (Hofsteded, 1980). This post is a repeat.

If you do read Culture's Consequences you will find that Hofestede's "Masculinity" factor, in which Japan came out way on top is defined in the same way as, and contains questionnaire items entirely applicable to Markus and Kitayama's (1991) Independent Self Construals, that is argued to be typical of Americans! E.g. "How important is it for you to work with people that cooperate well with one another?" or "How important is it for you to have a good working relationship with your manager?" are both items that correspond to femininity, that Japanese rated as being unimportant.

Markus and Hofesteded to agree however, that Independence is a masculine trait. Before she teamed up with Kitayama, Markus (Markus and Cross, 1990) wrote a very similar paper about the differences between men and women, even using most of the same data (such as Cousin's study) to support the assertion that there are two types of self construal, held by men and women. Personally I think that Markus is right on both counts, about the Japanese and about women. How could Hofstede get Japan so wrong? I guess it was because he was surveying Japanese IBM employees. Or is it because Japanese really are by far the most independent culture in the world?

In any event Hofsteded did a good job of spinning his surprising findings.

I admire all the people mentioned in this blog post.

Bibliography

Cousins, S. D. (1989). Culture and self-perception in Japan and the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 124.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review; Psychological Review, 98(2), 224. Retrieved from www.biu.ac.il/PS/docs/diesendruck/2.pdf

Markus, H., & Cross, S. (1990). The interpersonal self.

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japan, japanese culture, self, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Friday, November 02, 2012

Heejung Kim vs Japanese Architects and Designers

However, one of my favourite cultural psychologists, Hejung Kim (Kim and Markus, 1999; Kim and Sherman, 2008) had demonstrated that Asians Americans have less of a preference for unque figures than European Americans.

She had Asian and European americans evaluate the 9 parts of each of the digrams in the top of the above photo (Kim and Sherman, 2008, Kim and Markus, 1999) and found that the European Americans were more likely to choose the unique parts (M = 5.36, SD = 2.12) than the Asian Americans (Mean = 4.39, SD = 2.17).

Why is this? Were there in sufficient Japanese in the Asian sample? Or am I am I wrong; Harajuku fashionistas, and product innovators are not-represtentative of Japan.

I think that Japanese self presentation is not only visual, but as such, aesthetic. Just as Americans do not strive to be linguistically unique in naff ways, the Japanese don't choose clothes and products just because they are unique, but also because they look good. Conversely, American visual expressions (think of their bodies!) and Japanese linguistic expressions (think of traditional Japanese politicians) can be....less appealing.

The difference is in which media of self expression is important. Americans believe that appearance is skin deep. Japanese have negative words for language (rikutsu). Both Japanese and Americans admire uniqueness, but it is only in unimportant media of self expresion are people prepared to be naff to achieve uniqueness. The American preference for the sole isoceles triangle among the array of regular triangles in the diagram top left is just not aesthetic. It does not look nice and the Americans know it but they don't care about looks. The American preference for this irregular triangle is comparable to the anti-conformism found in Takano's experiment in Japan but not America. Japanese were prepared to give an incorrect (linguistic) answer in order to be unique, when all the confederates were saying the right answer, whereas Americans were not. The Japanese wanted uniqueness and did not care about being "right." In a medium that mattered to them, the Americans were not prepared to go that far.

I predict that Japanese will prefer the parts that are for instance at the top of the piramid, or centre of a pattern, or which hold an aesthetically privelidged position within the overall form. The Japanese may also demonstrate a preference for figures that are in harmony with the rest of the parts, since in Japan, being unique and yet in harmony are (from the philosophy of interdependence) not contradictory.

Indeed the people that we call unique, such as conductors, fashionistas, designers, and architects of know a lot about and produce a lot of things which demonstrate harmony.

I am going to repeat the experiment in my class and see which parts of the above diagrams the students prefer.

Bibliography

Heine, S.J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 879–887. Retrieved from http://www2.psych.ubc.ca/~heine/docs/2008Mirrors.pdf

Heine, Steven J. (2007). Cultural Psychology (First ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Kim, H., & Markus, H. R. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or conformity? A cultural analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(4), 785. Retrieved from http://www.psych.ucsb.edu/labs/kim/Site/Publications_files/Kim%26Sherman08.pdf

Kim, H. S., & Sherman, D. K. (2008). What Do We See in a Tilted Square? A Validation of the Figure Independence Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(1), 47–60. doi:10.1177/0146167207309198 Retrieved from http://www.psych.ucsb.edu/labs/kim/Site/Publications_files/Kim%26Sherman08.pdf

Leuers, T., & Sonoda, N. (1999). The eye of the other and the independent self of the Japanese. Symposium presentation at the 3rd Conference of the Asian Association of Social Psychology, Taipei, Taiwan. Retrieved from http://nihonbunka.com/docs/aasp99.htm

Labels: collectivism, culture, individualism, japan, japanese culture, Nacalian, nihonbunka, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Monday, October 29, 2012

Two Ways of Seeing a Mirror

The Japanese are found to be unaffected by mirrors (Heine, et al. 2008).

Social psychologists such as Dov Cohen, and Steven Heine, would, or do argue that mirrors are, for the Japanese who seem to have them in their heads, like the boy sees in them, a personification, internalistion of the other. In other words, mirrors can be understood to Japanese raise public self awareness. I argue that the mirror that the Japanese have in their heads is more like that of the girl in this comic.

The mirrors that Japanese do not need, and are are not influenced by, because they have intra-psychically simulated them to the piont that they have a mirror in their head, enables themselves to see themselves from their own point of view.

In other words, Japanese mental mirrors raise private self awareness and the Japanese are in a permanent state of high private self-awareness. This means, I predict that the same Japanese that are unaffected by mirrors are likely to conform less and be more aware of who they themselves are, two behaviour traits which are very inappropriate for collectivists.

Bibliography

Cohen, D., Hoshino-Browne, E., & Leung, A. K. (2007). Culture and the structure of personal experience: Insider and outsider phenomenologies of the self and social world. Advances in experimental social psychology, 39, 1–67.

Heine, S. J., Takemoto, T., Moskalenko, S., Lasaleta, J., & Henrich, J. (2008). Mirrors in the head: Cultural variation in objective self-awareness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 879–887. Retrieved from www2.psych.ubc.ca/~henrich/Website/Papers/Mirrors-pspb4%5...

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japan, japanese culture, mirror, Nacalian, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Japanese Aquisitions and Masaki Yuki's Research

I guess that it will depend upon the industry. In manufacturing and hard (as in hardware) industries the Japanese will bring with them praxis that is successful and will be respected by their Western workforce. But in industries whose products are formal (read linguistic) constructions, such as finance, (non-game) software and to a significant extent, advertising, importing Japanese workways may be more fraught.

If the Japanese managers read up on the cultural differences between Westerners and Japanese they may be persuaded that their new British employees need to be taught to be more harmonious, to work better in teams. If they reach this conclusion then I think that they will have been, in my humble opinion, misguided.

I want to recommend to the management at Dentsu the only mainstream research that espouses a qualitative rather than quantitative difference between Western and Japanese ways of thinking: the excellent research by Masaki Yuki (2003).

For the most part Japanese are argued to be more sensitive to the group (Hofsteded, 1991) or more sensitive to context and more information (the varied and also excellent research of Nisbett and Masuda). The mainstream rhetoric regarding the differences between Western and Japanese culture, is quantitative: one of more rather than less.