Tuesday, November 26, 2013

JapanAmerica

Steven Heine's extensive research has shown that the most robust distinction between Americans and Japanese is that the former are full of it - they praise themselves and others way out of proportion to reality. While American's engage in this linguistic ego massage, which in the USA is said to promote health, wealth and well-being, the Japanese have been, traditionally, if anything, linguistically self-critical. The greatest advantages of being self-critical is that it facilities self-improvement. Japanese reflect upon their own flaws (hansei) and then get ride of them (kaizen).

Alas, however, such is the hegemony and attraction of Western culture, (the bs, the auto affective self-narrative) that the Japanese are reading and publishing books instructing mothers to take it easy, get into "co-chingu" and above all indulge in praise, since praise is what decides how happy you are going to be. Praise, praise praise.

They are also writing books that trash upon the last bastion of Japanese culture - Japanese industry - since Japanese industry is not nice to young people -- such as for example, Tadashi Yanai (2009) who (rather than "praising") encourages himself and others to forget their successes as soon as they have achieved them.

Soon alas they may forget how to be Japanese, and end up as really low-grade Americans, since however much they practice they are never going to catch up with us. I grew up with people who are centuries ahead in their skill at auto-ego-massage. I think that if the Japanese go down that route, they are going to get right royally shafted. While it has its drawbacks, the only Japanese way forward is to hansei and kaizen.

The other thing that these JapanAmericans are forgetting is that while their words were always self-critical in the past, the Japanese have traditionally loved what they themselves looked like. They were quite positive enough without all the "self-enhancement".

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, westernisation, 日本文化, 欧米化

Sunday, November 03, 2013

Western Mannequins Japanese Rite of Passage

Even the display advertising kimono and hakama (traditional Japanese male formal attire) uses mannequins that are are at least partly Caucasian in appearance.

This is partly because it is cool to look bi-racial, due to the economic influence of the West, and due to the universal human tendency to prefer average faces.

It is also due to the way in which Japanese do not identify with self-narratives but rather with self-images. In Japan it is even more true that "Video Ergo Sum" (Lenggenhager, et al. 2007). If therefore Japanese mannequins were Japanese in feature they would appear eerily animate to Japanese shoppers, as do the status of Buddhas and Gods in Japanese temples and shrines. The use of Caucasian mannequins adds a element of distance, of inanimateness. To the Japanese, Westerners are a little like zombies or Gundam (robotic suits) with with they can identify - possess and control.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, reversal, westernisation, 日本文化

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

The Japanese Today

There is considerable research to suggest that many East Asians, at least from Hong Kong (e.g. Morris and Peng, 1994 or Norasakkunkit and Uchida, 2011a for a review on Japan) are bi-cultural in that they retain Asian culture while having been influenced by Western culture.

To my mind the Westernisation of the Japanese remains fairly superficial, in that while Japanese, especially young Japanese, now have bleached hair, double eyelids and avow Western values, such as autonomy and choice, they are "eggs", or my neoligism bean-bread-men: white on the outside but still thoroughly Japanese underneath.

An "egg," is a "racial slur" referring to a while male that has Japanised his heart partly in order to date Japanese women. In that sense I am attempting to be an egg. I am definitely white on the outside. I am not sure if I have succeeded 'yellowing' my heart.

The bean bread is made of an outsider layer of bread (often associated with Western society) coating a heart of sweet brown bean paste - a Japanese delicacy that is rather alien, not to say disgusting, to many Westerners. I love it. Like the egg, it is white on the outside, but the centre is the meaning, the truth, and raison d'etre of the brean bread bun.

I think to an extent many Japanese have become superficially Westernised, like bean bread buns. I do not see this as being a slur. The ability to incorporate, innovate, and create a hybrid - such as the bean bread bun - is famed facet of Japanese cultural evolution.

I worry though. It seems to me that bread and sweet bean paste don't mix. Furthermore it seems that some Japanese are becoming melon bread, a sort of soggy sweet bread with none of the important Japanese filling, or gumption, underneath.

In some important research by Norasakkunkit and Uchida (2011b) it was found that while non-marginalised Japanese youth in higher education showed the Japanese pattern of persevering more under critical conditions than under praise (Heine et al., 2001), the marginalised (NEET) youths needed -- like young Americans but possibly not as successfully American as young Americans -- needed to be praised.

The ability to take criticism, be grateful, be motivated and see criticism as a path to self improvement is perhaps the strongest and best part of the Japanese heart.

Bean bread buns - and bean bread men - banzai!

Heine, Steven J., et al. "Divergent consequences of success and failure in japan and north america: an investigation of self-improving motivations and malleable selves." Journal of personality and social psychology 81.4 (2001): 599.

Norasakkunkit, V., & Uchida, Y. (2011) Marginalized Japanese Youth in Post-Industrial Japan: Motivational Patterns, Self-Perceptions, and the Structural Foundations of Shifting Values.

Norasakkunkit, V., & Uchida, Y. (2011b). Psychological consequences of postindustrial anomie on self and motivation among Japanese youth. Journal of Social Issues, 67(4), 774-786.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, westernisation, 日本文化

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Nostalgia in Premodern Japan

I claim that the the Japanese love of historical theme parks, such as Furusato (home-towns/villages), Heide in Switzerland, Beatrix Potter in the UK, Anne of Green Gables in Prince Edward Island Canada, is indeed because the Japanese are attracted to nostalgia. But I believe the Japanese always have been wallowing in nostalgia because nostalgia is just pandemic in Japan. In the UK nostalgia is for old folks like myself, but in Japan even young people - e.g. my students - like to proclaim that something is "natsukashii!" (nostalgic). Things do not need to be all that old to be nostalgic. Indeed it helps if they are not so that young people can remember them.

The Japanese love of nostalgia has nothing to do with the West.

The point I want to make is that the Japanese interest in nostalgia has little to do with a yearning for a pre-modernised, pre-Westernised Japan. The Japanese have been into nostalgia for a long time, well before anything that might be described as modern or western and an impact upon Japanese society. Nostalgia lies on the same emotional seam as wabi, sabi and aware, the wet, masochistic love of the unfolding of time, as manifested in solitude and decay, and the Japanese were into this aesthetic since the dawn of recorded history.

In one of the earliest travelogues (Zouki, c975) and the earliest poetic diary describing a pilgrimage the author visits places significant in Japanese mythology, and reminisces about the time of the gods all the while typically Japanese aesthetic enjoying the impermanence of things.

ねがはくはわれ、春は花を見、秋はもみぢを見るとも、にほひにふれ色にめでつる心なく、朝の露夕の月をみるとも、せけんのはかなきことををしへ給へ。

If possible I would like watch flowers in spring, and the red leaves in autumn, smelling nature and yet without a wish to make any of these my prize, look upon the dew at dawn and the moon in the evenings sky and from them learn of the impermanence of the world.

Seven hundred years later, in 1689, the post travelling poet, Matsuo Basho waxes lyrical about ancient "ruins" (see Hudson, 1999, p1-2) as mentioned in a previous post. Basho visits sites where there is nothing to see but grass, and is moved to weeping by a sense of nostalgic impermanence.

At a stone commemorating a castle long since destroyed, Basho writes, "Time passes and the world changes. The remains of the past are shrouded in uncertainty. And yet, here before my eyes was a monument which none would deny had lasted a thousand years. I felt as if I were looking into the minds of the men of old...I forgot the weariness of my journey and was moved to tears of Joy." (Keene, 1955, p366 in Hudson, 1999, p1) .

And in one of his most famous poems composed at site of a once famous samurai family, where now only summer grass remains, he writes (Basho, 1997):

夏艸や兵どもが夢の跡 Summer Grass, Warriors, Trace of their dreams

Donald Keene (1999) claims that Basho was so into nostalgia, or at least reliving literary precedent, that he only commented on scenes that had been mentioned by previous poets.

"He (Basho) had absolutely no desire to be the first ever to set foot atop a mountain peak or to notice some site that earlier poets had ignored. On the contrary, no matter how spectacular a landscape might be, unless it had attracted the attention of his predecessors, the lack of poetic overtones deprived it of charm for Basho. When, for example, he travelled along a stretch of the sear of Japan coast that inspired no important poems, he did not mention the scenery" (Keene, 1999, p 311 in Watkins, 2008, p101).

Another 250 years later a cultured traveller Kikushi Tamiko (1821) set off "in a cultural quest for the locations and events made famous by the texts that she had read"(Nenzi, 2004, p). Once again, her criteria of selection "in terms of its presence (or absence) in the pages of classical literature," (Ibid, p291). The innate beauty of the destination did not matter because, according to Nenzi (ibid), "For culture travellers, the essence of the experience of meisho [named-places] was to recover "the idea behind" rather than to delve into the present substance of the sight."

Basho was clearly not alone, but part of an immense tradition that he helped to perpetuate. When a lowly warrior was sent from Kurume City (my old town) to Tokyo, then Edo, in 1839 as part of the alternate attendance/hostage system (Sankinkoutai), he wrote in his diary "While in Edo, we may also go to see the places where Basho visited, and this brings on great nostalgia."(Aoki, 2005, in Vaporis, 1996, p296)

At about the same period, more than a decade before the opening of Japan to the Wet, the Suma Diary (Kagawa, 1847) details a trip to Sumaura in what is now Hyougo Prefecture, to the ruins of the palace of one of the poets whose poem was featured in the famous collection of 100 poets used on Japanese playing cards, originally from the second most famous old book of poetry (Saeki, 1981).

Here below is the excerpt from the travel diary above, translated with a little help from my Japanese wife, and with my attempt at a modern Japanese, non poetic version in brackets.

願ひし須磨の浦につく。 (願った行き先である須磨の浦に到着しました。)

I arrive at Suma Bay, the place I had been yearning to reach.

先ここよりの見渡し。海上のけしき。(この先からの見渡しは海上の景色)

The view from here is out over the sea.

更に類なし。只あはれあわれと見るのみ。(類がないほど、ただ哀れみな光景だけを見る)

There is nothing like it. Just a wilderness of water.

中々に事の葉に。言続けむも。今更びたり。(書き続けてもなかなか言葉になりません。)

It is not easy to put into words, even if I go on talking. And even now??

家毎に。かの竹簾かげ下ろして。故ありげに住みなしたる。(家ごとにその竹のすだれが下ろされて、理由があるかのように住み。。。。?)

At each house the bamboo blinds are down. As if they have a reason for (not) living here?? (Maybe suggesting that they are waiting).

いかでかゝげ寄らまほしきまで。なつかし。(さっぱり分かりません。懐かしい!)

???? Nostalgic.

案内の翁を雇ひ出たり。先にたして行く行く語らく。あれ見給へ。かの小さき山こそ。(おじいさんの案内者を雇って出発しました。語りながら先に進んでいった。あれ見てよ。この小さい山こそ!

I hired an old man guide. We went on together talking. Look at that. At that little mountain there.

中納言行平の君。この浦に汐くみしておはせし時。(中納言行平という昔の偉い詩人がこの浦から汐をくみにきたとき)

When Lord Yukihira Chunagon went to get water from the bay.

立帰りいなばの山のと。((百人一首にでる)「立ち別れの因幡の山」のことですよ!)

This is the Inaba Mountain in the poem (one of the 100 that are told at new year).

ながめ給し濱にて侍れ。(眺めて、濱においで??)

Stare and go (come?) from/to the beach.

いでとく書きとめ給へなどを。?えもあらぬくさぐさの事をいふなむ。(??)

?????

中々興ある。さるあひだ。(中々興味深い。???)

Very interesting! ???

須磨寺を始め。内裏の跡。一の谷。(須磨というお寺を始め、中納言の宮殿の奥の部分の跡。一の谷?)

Starting with Suma Temple, the ruins of the palace, and the Ichinotani battlefield.

上の秋草をさへ。かぞへ見廻りて。(その跡の上に生える草をさえ数えるかように見回っていた)

I even started to count the autumn grass above (the ruins) with my eyes.

海ばたの松陰なる。(海辺の松影になるように)

Becoming like the shadow of a pine (this may be another reference to the woman in the aforemented poem who was told to wait like a pine tree for her lord to come back to her.)

敦盛りぬしの塚を拝む。(あつもりの塚を拝む)

I prayed at the burial mound of Taira no Atsumori.

たえず浪風の音。ひヾき通ひて。(浪と風の音がたえず響き通って)

And all the while, the sounds of the wind and waves, runs through me.

昔のおもかげ。目の前に浮かびつ。(昔の面影が目の前に浮かびうがってきた)

And the memory of you, (my lord) rises before my eyes.

たちよれば君を忍ぶの草おひてあらぬ露さへおきそはりけり (たちよったら中納言の君を忍ぶ草にあった露さえ落ち添わった。)

Having paid my visit, even the dew on the grass that remembers you has increased.

(This is a reference to another ancient poem --kokinshuu, 545 -- and suggests that the author is crying and thus increasing the dew)

見る處なつかしかるぬはなし。(見るところ、光景は懐かしく思わずにいられない。)

I can't but be nostalgic about the place I am seeing.

(Corrections gratefully received!)

In other words, the author, went to some lonely spot on the coast of Japan in what is now Hyougo Prefecture, to the site of the residence of one of the poets who had been famous almost one thousand years years previously, and then, staring at sea and grass, he felt an image of that lonely, ancient, love-struck poet spring to mind. And imagining the ancient poet, this tourist wept, mega-nostalgically. Contra Urry (2002), in this most quintessentially Japanese touristic experience, there was nothing to be seen. There was only grass, only sea. There was nothing that the tourist or traveller could not have seen in many other places far nearer to home. But at the same time, the author did see, did experience nostalgia and the pity of things (mono no aware), because the traveller called images to mind.

Japanese "site-seeing" (thing seeing: kenbutsu, 見物) is about seeing but not of sights, not of external visual images, but rather of visions: physical absence juxtaposed with images in the heart.

Afterword

In order to bring the observations above back to a theory of the visual-imaginary (Takemoto, 2002), or "lococentrism" (Lebra, 2004) of the Japanese self, I might perhaps go via "phallocentrism"(Spivak, 1976). The narratival, linguistic self is that which is accompanies identification with the symbolic parent. whereas the visual-imaginary self is that which accompanies identification with the primary care giver (Lacan, 1949). I could then link nostalgia with "pay-forward" and pay-back families as I did in my last post. In order to link nostalgia with lococentrism directly, would have to create a deconstruction of the theory of place (Nishida, 1987)!

Western theorists (Mead, 1967; Lacan, 1949) insist that visual self-identification can only take place in the presence of a real other (mirror or person) and that the subject is thus never free to develop or simulate an objective, generalised view on self. While the visual is decried in this way language is seen to provide a "generalised" (Mead, 1967), capitalised (Other, Lacan, 1998), "super" (Bakhtin, 1986) objective 'perspective' on self a priori. Above all, visual self-views are almost always considered to be external (e.g. Cohen & Gunz, 2002), whereas linguistic representations of self are seen to be somehow inherently private or at least internalisable (for exceptions see Duranti, 1986; Koster, 2009; Wittgenstein, 1973, and to an extent Derrida).

Derrida sees nostalgia (Derrida, 1998, p240) as a desire for time before language, "[The] Dream of a mute society, of a society before the origin of languages, that is to say, strictly speaking, a society before society." From a position within the logocentric tradition that he is critiquing, Derrida, sees this nostalgic longing for self presence, or authenticity, as a longing for self before self. This critique is founded in the impossibility of non-linguistic self-reference (or even non-referential self-reference).

Accepting this contradiction, Nishida (1987) argues that a phenomenological -- and I would say viso-imaginary -- self-experience can be achieved even as, or especially once, language is expunged. Once language is externalised, it is possible to experience an "absolutely contradictory self indentity:" self as the immediate environment, self as place. Japanese tourists aim to achieve this kind of pre-symbolic authenticity, by visiting the symbolic sites, sights which have themselves become markers, deliciously, from a Japanese viewpoint, "encrusted with renown" (Culler, 1988, p8 in the online version).

Words do always result in "differance" (Derrida, 1998), but images are not "timed"(contra Fenollosa & Pound, 1936). Whereas words are always differed, mean something in the future, images are always of something recalled, already in the past. The Japanese tourist is not loving any image real or imagined, but the place in which it appears.

Hmm, really riffing here...Derrida says that the phoneme results in differance. But while phonemes do exist in time they only point forwards in time under the assumption of a static presence or place. If he insists on any before and after then Derrida is as nostalgic as Rousseau, or our tourist. It is the admixture of place that makes the phoneme forward speaking. Conversely it is the removal of temporally differing language that makes the place, the mirror shine brightest in recollection of the past.

Incidentally, the opposite of nostalgia is hope and we, Westerners, are awash with it. I am hoping I make sense one day:-)

Bibliography

Ashkenazi, M. (2001). Omiyage: Constructed Memories and Reconstructed Travel in Japan. In H. Walker (Ed.), Food and the Memory: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooking, 2000 (p. 31). Oxford Symposium.

Aoki, N. 青木直己. (2005). 幕末単身赴任 下級武士の食日記. 日本放送出版協会.

Askew, R. K. (2007). The politics of nostalgia: museum representations of Lafcadio Hearn in Japan. museum and society, 5(3), 131–147.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. (V. W. McGee, Trans.) (Second Printing.). University of Texas Press.

Cohen, D., & Gunz, A. (2002). As seen by the other...: perspectives on the self in the memories and emotional perceptions of Easterners and Westerners. Psychological Science, 13(1), 55–59. Retrieved from http://web.missouri.edu/~ajgbp7/personal/Cohen_Gunz_2002.pdf

Culler, J. D. (1988). The Semiotics of Tourism. Framing the sign. Univ. of Oklahoma Pr.

Derrida, J. (1998). Of Grammatology. JHU Press.

Hudson, M. (1999). Ruins of identity: ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands. University of Hawaii Press.

Fenollosa, E., & Pound, E. (1936). The Chinese written character as a medium for poetry: a critical edition. Fordham University Press.

Gerster, R. (2006). The past as a foreign country: nostalgia and nationalism in contemporary Japanese tourism. Tourism Review International, 9(3), 293–301.

Keene, D. (1999). Travelers of a Hundred Ages. Columbia University Press.

Koster, J. (n.d.). Meaning and the extended mind. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.let.rug.nl/koster/papers/extended%20mind.pdf

Lacan, J. (1949). The mirror stage as formative of the function of the I as revealed in psychoanalytic experience. Cultural Theory and Popular Culture. A Reader, 287–292.

Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist (Vol. 1). The University of Chicago Press.

Nishida, K. 西田幾多郎 (1987). 場所. in 上田閑照編 西田幾多郎哲学論集〈1〉場所・私と汝 他六篇. 岩波書店.

Nenzi, L. (2004). Cultured Travelers and Consumer Tourists in Edo-Period Sagami. Monumenta Nipponica, 59(3), 285–319.

Rea, M. H. (2000). A Furusato Away from Home. Annals of tourism research, 27(3), 638–660.

Robertson, J. (1988). Furusato Japan: the culture and politics of nostalgia. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 1(4), 494–518.

Saeki, U. 佐伯梅友. (1981). 古今和歌集. 岩波書店.

Spivak, G. C. (1976). Translator’s preface. Of Grammatology, 9–38.

Takemoto, T. (2002). 鏡の前の日本人. ニッポンは面白いか (講談社選書メチエ. 講談社.

Vaporis, C. N. (1996). A Tour of Duty: Kurume hanshi Edo kinban nagaya emaki. Monumenta Nipponica, 51(3), 279–307.

Urry, J. (2002). The Tourist Gaze. SAGE.

Watkins, L. (2008). Japanese Travel Culture: An Investigation of the Links between Early Japanese Pilgrimage and Modern Japanese Travel Behaviour. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 10(2), 93–110.

Diary and Poems

Kagawa, K. 香川景周. (1847). 須磨日記 (Suma Diary my trans). In 岸上質賢 (Ed.) "續紀行文集". Retrieved from books.google.co.jp/books?id=qKk9as-h84kC&printsec=fro...

【百人一首講座】立ち別れいなばの山の峰に生ふる まつとしきかば今かへり来む─中納言行平 京都せんべい おかき専門店【長岡京小倉山荘】. (n.d.). Retrieved April 24, 2012, from www.ogurasansou.co.jp/site/hyakunin/016.html

Kokinshuu 古今和歌集の部屋. (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2012, from http://www.milord-club.com/Kokin/uta0545.htm

Matuso, B. 松尾 芭蕉. (1997). 芭蕉自筆奥の細道. (上野 洋三 & 桜井 武次郎, Eds.). 岩波書店.

Labels: image, japan, japanese culture, Jaques Lacan, lacan, logos, mirror, nihobunka, nihonbunka, occularcentrism, specular, westernisation, 日本文化

Monday, March 05, 2012

Individualistic Second-Hand Japanese Vinyl

An enthusiastic and intelligent overseas student (Ng, 2012) wrote an interesting term paper about Japanese collectivism and Western Individualism as demonstrated by Japanese and American pop.

It is clear that at the moment in Japan, groups are in, whereas Solo artists (leading armies of backing dancers) are the rage in the US. As Ng points out, the number of people on screen in the videos may not differ but the appellation given to the ensemble is in opposition. Two singers and twelve dancers are called a group (Exile) , or "company", in Japan, whereas Nicki Minaj and her entourage of clones performing Super Bass, is referred to as a work by a solo artist in the USA.

At the moment AKB48 and other mass produced girl bands and boy bands (if they can even be called bands, they are more like a brand or football team) are very popular.

A quick look at the Oricon Charts and the Billboard 100 showed me that while 6 out of 10 of the Japanese top ten were bands, 7 out of the top ten US acts were solo artists.

As I have argued before, the existences of collectivist/individualist heroes does not necessarily portray the reality of a society, but rather what it aspires to. And what a society aspires to, may be that which it lacks, the latter being the position I champion at the present time.

As the Japanese in the digital age return to their roots, they become more and more enamored of groups, just as they loose their ability to join them.

Has it always been that way? I happened to be in second hand store in Japan and went through a bin of second hand vinyl, mainly 80's pop. Of the 14 Japanese LP's that I sampled there was one duet (top right), two bands (The Checkers and The Kaiband) and eleven LP's by ten solo artists. Does this mean that the Japanese in the eighties were individualists? Research by Hamamoto and Harihara, on the contrary argues that individualism is on the rise in Japan.

There also happened to be two Western LP's: Dire Straits' Making Movies (including one of my favorite songs of all time) and an LP by the Carpenters.

Pop music is an area of Japanese culture that is tremendously influenced by the West, so even if it were the case that 80's Japanese liked solo artists, it could easily be argued that this is partly due to the Western influence. In any event it would be interesting to do a historical analysis of the Japanese Oricon charts and Billboard to see which has more groups.

Ng, Y.. (2012) "Analysis of the Music industry in Japan and America via cultural psychology," unpublished term paper.

LP covers copyright their creators. Please leave a comment to have this removed from the Net. 取り下げご希望でありましたら、下記のコメント欄かhttp://nihonbunka.comのメールリンクからご連絡ください。

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japan, japanese culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, westernisation, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

The Deaf and The Japanese

If there is any truth in the assertion that there is something visual rather than verbal, about the way that the Japanese sign, i.e. that Japanese culture leans toward the right hand side of the diagram of Dual Coding Theory, then one might expect them to share some similarities with those deaf that use visual sign systems (ASL and JSL). To investigate this hypothesis I read Oliver Sacks’ “Seeing Voices” an excellent, and even moving, introduction to the world of the deaf, and particularly their ability to communicate using sign language, from the perspective of a neurologist.

First of all, Sacks points out that deaf signers are better at interpreting Chinese characters signed in the air, and it is clear that Japanese people are far better at signing and reading characters in the air (p78) but that maybe the single case in point. Deaf people use Sign (ASL, JSL) which, though visual, has meaning. Japanese use Chinese characters which, though visual, have meaning.

Oliver Sacks points out that there are those that deny even this similarity, since there are those (including Roland Barthes) who deny that the visual can have meaning at all. But even accepting the premise of Sacks’ book, that language can be seen, perhaps the similarity between the deaf and the Japanese starts and ends with a trivial resemblance between Sign and Kanji.

Cutting to the chase, Sacks' book being a book about deaf, rather than a book about the deaf and the Japanese, does little to demonstrate similarities between deaf and Japanese culture. "Seeing Voices" does however, point to some possibilities and perhaps the most tantilising of these lies in Sacks observation that Sign language is not only a language for communicating with others, but also for thinking and for communicating with oneself. He provides clear evidence that the deaf Sign to themselves, and sign in their dreams. I have also noted that Japanese have a tendency to sign to themselves, such as Ichiro's famous baseball bat point, or more particularly the safety oriented pointing checks performed by those working on the Japanese railway system, for example. Sack's goes on assert, as a footnote (26) to page 59, given on page 161 of my version of the book, the use of sign as thought, not only to others but to and about oneself, by application of the Sapir-Whorph hyphotesis, may result in a "hypervisual cognitive style". I believe that this phrase may be appropriate to use about the Japanese as well.

Sacks claims that users of Sign, adept as they are at reading, and making (or is that speaking) visual meaning, often become “visual experts,” adept not just at “a visual language but [having] a special visual sensibility and intelligence as well.” (p84) Alas Sacks does not go into concrete cultural details of deaf visual expertise. Sacks does not mention that the deaf are good at anime, manga, computer games, architecture, manufacturing, visually stunning food preparation, becoming highly attractive idols, or many of the other things at which the Japanese may be argued to excel.

Sacks points out that deaf understanding of facial expressions may be better than that of the hearing. Alas research about Japanese interpretation of gesture is mixed. David Matsumoto points out Japanese inability to read “universal” emotions. Keiko Ishii demonstrates that Japanese can be more sensitive to the degree to which people smile (or at least when smiles disappear).

Most surprisingly, the neurological evidence that Sacks presents seems almost to directly contradict any assertion of similarities between the Japanese and the deaf. Sacks points out that deaf process Sign with their left brain, the same hemisphere that the hearing use to understand speec. He shows that deaf signers pull some seemingly non-linguistic (among hearers) processing, such as the processing of facial expressions, into their left/linguistic brain. Sacks further suggests that the left brain is well adapted to language and argues that there are deficiencies in right brain language. Research on neurological differences between Japanese and Westerners, is still fairly new or controversial, but, it is claimed that Japanese visual signs (Kanji) are processed at least in part by the right brain (E.g. Nakagawa 1993) and that Japanese pull the procession of phonic information (such as the sound of insect noises and music) into their linguistic left brain. If this is the case then, it would suggest that Kanji, processed as they are by the side of the brain not well suited to language, would have a deleterious affect upon Japanese language processing. And even that the Japanese are hyper-phonic, as oppose to hyper visual (like the deaf), since it is sounds that the Japanese process with the ‘linguistically superior,’ left hand side of the brain.

In order to achieve the sort of revolution that Sacks describes, being achieved by the deaf: that they, their visual culture, their Sign is not just a pantomime, but equally meaningful, one would have to go further even that Sacks avows. Sacks demonstrates that the visual and the deaf can be just as good as the oral/hearing, just that they do what they do in a different way. How much more difficult would it be to argue that the right brain is just as good at processing the world, but in a different way? This is not a path that Sacks, a Western neurologist, attempts to follow in this book at least (but see his "The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat").

Sacks’ description of the revolution underway in the world of the deaf, of how they are achieving a hard-won cultural autonomy, a reappraisal such that they are now different, rather than diseased was particularly moving. Perhaps I am romanticising Japanese culture too much, but it was in the description of the revolution, or the potential for one, that I found the greatest potential similarity between the deaf and the Japanese. It seems to me that being Japanese is not yet “depathologized” (p120), with commentators and educators in Japan still tending to present the West as being advanced, a model that Japan should still (after all these years) be aiming towards.

Sacks argues that deaf were initially non-receptive to the idea that Sign could be a language, or that it could be analysed, and were self-deprecating with regard to their visual culture (p114-115). I find that mystifying, empty-centred, self-deprecating theories of Japanese culture are still fairly mainstream, at least in academe. Will there one day be a Japanese cultural revolution, such as being experienced by the deaf or will Japan Westernise itself out of existence first? Or is this endeavour itself bogus, the product of another white male mind (my own), since the right brain, or where ever Japanese cultural excellence is situated may have no need of affirmative analysis.

Finally, Sacks makes the point that the deaf are not dumb, both in the sense that they are not stupid and in the sense that they can speak. In other words Sacks saves the deaf from perjorative appraisal, by pointing out that the deaf can in fact speak, in their own language, so they are not dumb -- in any sense but-- but rather different. Sacks writes "..for it is only through language that we enter fully into our human estate and culture, communicate freely with our fellows, aquire and share information. If we cannot do this....we may be so little able to realise our intellectual capabilities as to appear mentally defective. It was for this reason that the congenitally deaf, or "deaf and dumb" were considered "dumb" (stupid) for thousands of years...p8" This all sounds very brave and stirring, and it is, because Sacks succeeds in releasing the deaf from this derogatory appelation. But what of the "dumb"? People who can not speak, who are aphaisic, who do not have language remain in Sacks' view, unable to realise their intellectual capabilities. According to Sacks the dumb remain dumb; those without speech are intellectually impaired because speech is required for intellectual functioning.

This is a shame, and I believe unfair. in Sack's earlier book "The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat" in the essay "The Presidents' Speech" Sacks describes how even aphaisics, who do not have the ability to understand language, where nevertheless able to understand most of what is going on around them, even a presidential speech, perhaps even more than those that can hear and understand the words. What happened to the possibility that the ability to use language is just another one of many human abilities? Is the mastery of language essential to enter "our human estate" (whatever that may be) and culture? Is the use of a media of interpersonal communication for thought ("self-communication" as if it were not-an oxymoron) an essential prerequisite for thinking? Even assuming that that symbols are necessecessary for thought, is it a given that symbols that are good to think with, are also those that are good to communicate with. If the deaf can manage to think and communicate among themselves using sign and to communicate with the hearing using speech, then perhaps it is possible that the Japanese may be thinking in symbols that the are not using for speaking.

It seems that in the West at least, linguistic ability is considered to be a prerequisite, thinking is regarded as being self-communication using the same linguistic symbols that we use to speak to others, and thus those that can not speak are, even by Oliver Sacks, considered to be unable to think effectively. When reappraising a group that hithertoo been considered inferior, advocates posit the existance of another language (this work), a different voice (Gilligan, 1972 on women), their own words (Meltzer, 1987, on American Blacks) which, when we the outgroup understand it, will allow us to understand their excellence. But perhaps the Japanese do not have another language. Perhaps Japanese excellence is not to be found in any language. All the same the Japanese may be affirmative enough as they are. They just don't talk about it. The may not talk the talk, but they do walk the walk and always have.

The above image containts a cropped version of the cover design of Oliver Sacks' book "Seeing Voices" by Chipp Kidd

Labels: culture, japan, japanese culture, manga, nihobunka, nihonbunka, theory, westernisation, 日本文化, 欧米化

Tuesday, February 08, 2011

Child Abduction, the Hague Convention and Japanese Culture 2

This issue is massive, and massively tragic. The agony and the outrage are palpable.

I beileve that if I were in the position of a parent whose child were 'abducted,' I would be feeling the same way, reacting in the same way, decrying, petitioning, lobbying and doing all that is in my power to affect change, in the same way, in any way, with all my heart and all my strength.

At the same time, I ask myself, do the Japanese believe in justice, law and the rights of their chidlren? I am sure that the Japanese do. And yet, there is a real tragedy.

I think there are important, equally massive, cultural differences.

If I were to put this opinion - that there are 'cultural differences' - to a Western estranged parent, I would expect them to say, "Oh cutural differences! What bull! Another name, another excuse for gross injustice."

So, I am not suggesting that nothing should change. But there are two ways of making change, two types of change that one might hope for:

1) That change be made at the national/cultural boundary.

If one believes that there are cultural differences, then one may strive for change at the boundary between cultures, such that parents from other nations be given rights under Japanese law that are not given to Japanese parents, due to the fact that the marriages were based in more than one culture, in more than one law.

2) That changes should be made universaly, applying in Japan too.

If one believes that the Japanese, as they stand, do not respect justice, law, and the rights of their children (as is argued by many estranged Western parents) then the change that needs to be made is of type (2): All parents, be they non-Japanese or Japanese, should be allowed dual custody because the present Japanese system is just bad, patently and universally bad.

I think that (1) is the answer, because it will be more likely to succeed, because the Japanese family system works, and because change at the former level will not destroy Japanese society. Change as an exception, for predominantly Western fathers, is more likey to succeed because it will not devastate Japanese culture. I think that dual custody if made law in Japan would have enourmously adverse effects.

It seems to me that in Japan people get married primarily in order to have custody of, that is to say to have relationships with, children. If dual custody were enforced, and the realisation of its enforcement were to sink in, to become a commonplace, become accepted from the outset, then that would be the end of the Japanese family. Kaput.

I suspect that the legitimization of dual custody in Japan would be akin to the legitimization of marital infidelity in the West. It would make the critical family bond in each culture meaningless. The concept of family would be negated.

Labels: culture, nihobunka, nihonbunka, sex, westernisation

Sunday, May 23, 2010

Engrish T-Shirts

About half of the T-shirts on sale in Japan have lettering on them. Of those that do, 99% have English or rather Engrish printed upon them. It is almost impossible to find T-shirts with Japanese language written on them. Imagine if it were impossible to purchase English language T-shirts in the UK, and that all lettering on them were in Bad Japanese. There would be riots.

Perhaps this is not just the effect of Westernization, but also something to do with the way in which Japanese have always imported languages from other nations? Perhaps even if there were no Western influence upon Japan, the Japanese would not wish to write in Japanese upon their own T-shirts. Be that as may, I find the Engrish T-shirts a little more troubling than many of the locals.

At the same time, lately, I have taken to wearing a T-shirt upon which is emblazoned "Do! Something on your own way."

Labels: westernisation, 日本文化, 欧米化

Sunday, April 11, 2010

Electronics Graveyard

These days consumer electronics, such as TV sets and refrigerators, do not find their way into the rubbish (garbage), since they have to be taken to recycle centres, in the form of local electronic supplies stores.

Labels: culture, economics, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, westernisation, 日本文化

Monday, April 06, 2009

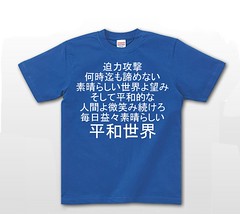

Hsirgne

hsirgne

Originally uploaded by timtakA back-translation of a T shirt, with English-like writing on it, sold in Japan.

The original has

"Impact attack never give up

Hope wonderful woeld.

And Peaceful.

All peopel keep smiling

Everyday.

More & More.

Fatastic.

Peace World."

Imagine if all the Tshirts on sale in clothes shops in the US or the UK had designs like the above. That is the situation in Japan. A large proportion of the Tshirts being worn and in the shops have English-like writing on them if they have any sort of print or patter at all. No one seems to think that it is in any way notable. It seems to me to be indicative of the fact that Western, particularly US, culture has become so desirable that Japanese people want to put its signs on their bodies. That the Japanese wear T-shirts like this suggests to me that Western culture is valued so highly that the same people probably also import Western culture into their minds.

イギリスかアメリカの店に入って、そこにあるTシャツの全てがこのようなデザインだったらどう思われるでしょう。日本人が着ているTシャツのほとんどは、上のようなものです。日本では特別視される事態ではありません。欧米、特にアメリカの文化がその表彰を体に一杯付けたいほど高く評価されていることを示唆していると思います。また、このようなTシャツを着ているのであれば、ここまで英語圏の文化が高く拝められるものであれば、欧米の精神的な文化(思想・価値観など)を心の中にも輸入していると思われるでしょう。

Labels: culture, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, reversal, westernisation, 日本文化

Sunday, August 06, 2006

Wanting to be White

Labels: culture, japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, westernisation, 日本文化

Monday, May 22, 2006

Oshare Majou (The Best Dressed Witch)

The Sega video game, "Oshare Majou Mahou Card" (Magic Card of the Best Dressed Witch), allows Japanese girls to turn themselves into well dressed dancing caucasians in the virtual.

Oshare means "dressed up" or "well dressed" but as well see, this is a competitive game so I have rendered it as "Best Dressed"

The official site is in Japanese.

The game seems to be a combination of a virtual version of the video dance game "Dance Dance Revolution," and virtual fashion using swipe cards, in a competitive format. Players purchase clothes which their virtual personas wear before taking on the computer or a friend in a battle of who is the most "oshare," where oshare means well dressed and cooly attractive at dancing. By pressing the keys in time with the music, the young lady with the best fashion sense (I am not sure of the criteria) and best moves, wins the battle of the Best Dressed Witch. Perhaps this information is stored on the swipe card. I am not sure.

The two girls are called "Rabu and Beri-" ("Love and Berry") often being appended to "RabuBeri" or "Raberi" ("lovely"). In their cartoon form these characters are pretty Mid Pacific as are many manga characters, with features that do not define them as being part of any race or nation.

Recently two caucasian models have been used to represent Love and Berry in some magazine adverts directed at young girls.

The game is enjoying immense popularity with cues of preteen girls and their parents forming at video arcades all over Japan.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, westernisation, 日本文化

Thursday, October 13, 2005

Michael Jackson Syndrome

These hair bleach products from more than one manufacturer. They are the last row of goods before the checkout in my local supermarket. Products placed just before the checkout are those which encourage impulse buying such as cigarettes, glossy magazines, and choclates. Hair bleach, like pictures of movie stars, offers a method of instant escape. Men of women bleaching their thick straight black hair dream of leaving the humdrum world of supermarket checkouts, to join the green-eyed and blonde gods in the stars.

But why green eyed, why blonde? There is nothing more natural about a Japanese person with blonde hair than blue, or green eyes than pink. The fact that they come as a set blonde hair and green (or blue) eyes, suggests to me that the dream comes from the West. There is research which suggests that the more that Japanese believe themselves to look like Japanese, the more they believe they are ugly. This is a very sad, tragic state of affairs.

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, westernisation, 日本文化

Wednesday, August 17, 2005

Blonde Japanese Dolls

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, westernisation, 日本文化

Nose Clamp

On front

CoCo

Nose Up!

(Anti-bacterial, Anti-odorant. New Release)

Make your little nose shine more beautifully. An essential product for your nose.

On rear (cartoon)

So where and when do you use CoCo?

"Just like me, sniff." thinks a brown haired Asian, wearing a nose clamp, while a watching blonde person on television)

On rear (instruction for use)

1) Adjust the screws at the end so that it does not hurt your nose while clamping.

2) Once you have adjusted the size, quietly (sic. gently) clamp your nose with CoCo.

3) Do not use for long periods of time.

4) Please stop using this device immediately should anything happen to your skin etc.

5) Do not use while driving or sleeping.

6) Keep out of reach of children.

Made in Korea, Imported by Sera in Tokyou, 03-3863-6091

I think that the preference for pointed noses is partly a subliminal effect of watching Western movies. Westernisation through the media helps to foster a creeping racial self-hatred among the not-long-nosed races. In any event, as Kowner (2004) has shown, the more Japanese believe themselves to have traditional Japanese features, the more they believe themselves to be unattractive. Isn't that horribly tragic? If I were Japanese I would feel antipathy towards products like this.

Fortunately, due to Japanese occularcentrism, the Japanese have a far greater tendency to emulate the Western look than the Western mind, but alas, there is a growing tendency to import Western psychology too. Bibliography

Kowner, R. (2004). When Ideals Are Too‘ Far Off’: Physical Self-Ideal Discrepancy and Body Dissatisfaction in Japan. Genetic, social, and general psychology monographs, 130(4), 333–364. Retrieved from http://east-asia.haifa.ac.il/staff/kovner/%2818%29Kowner.2004b.pdf

Labels: japan, japanese culture, nihonbunka, westernisation, 日本文化

This blog represents the opinions of the author, Timothy Takemoto, and not the opinions of his employer.