Wednesday, October 26, 2016

Reading the Customers Mind

Reading the Customers Mind

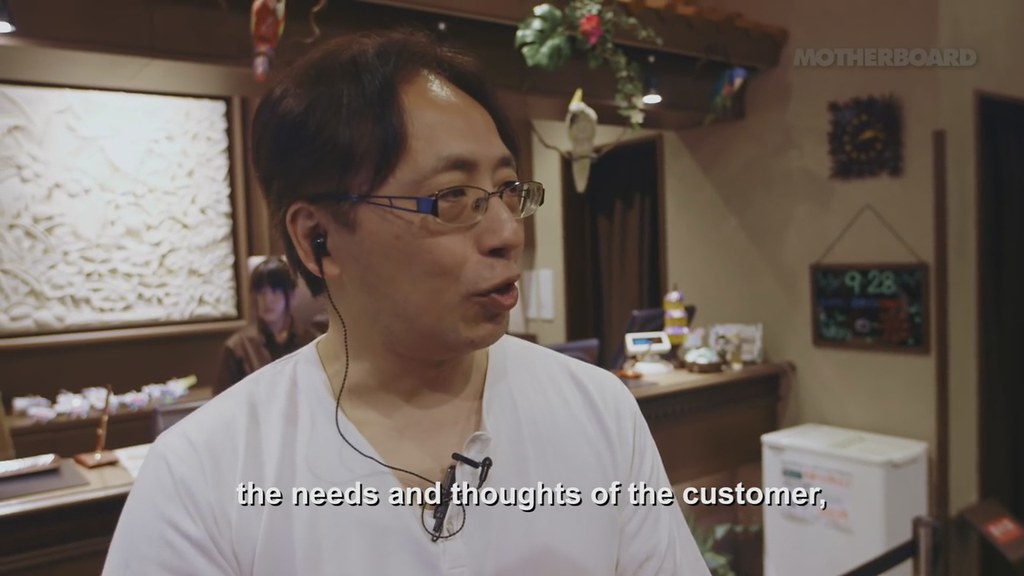

A Japanese capsule hotel manager, Akikazu Fukumoto, explains the essence of Japanese style hospitality (omotenashi) and why it would be impossible to replace his staff with robots in two sentences,

at the three minute mark in a video on robot staffed hotels in Japan by Motherboard.

My translation (for the original Japanese see below)

"Our hotel has the heart of Japanese hospitality (omotenashi no kokoro) and must therefore be staffed by humans. Our staff must be human because we behave proactively anticipating the thoughts and needs of the customer. "

The Motherboard translation is slightly off the mark since the hotelier does not "respond" to the needs and thoughts of the customer but pre-empt -- saki mawari, literally go around in front of -- them. If it were merely a case of "responding" to the needs and thoughts of their guests, the hotel could wait for the guests to express them verbally, and use robots, or untrained staff working to a manual, as is the case in Western style, customer makes overt choices, "help yourself" (Doi, 1973, p.13) hospitality.

Japanese hospitality is, when it works, a sort of "mirror dance" (Krieger, 1983) where the providers read the minds of their customers via their faces and behaviour, adjusting their own behaviour on the fly accordingly.

Contra what I have written elsewhere however, this hotelier seems to be implying that the thoughts of the customer are not expressed by their behaviour but come afterwards, perhaps in linguistic form. At its most effective, Japanese hospitality should preempt, and even prevent, the arrival of such thoughts by satisfying the need before the thought arises. The manager also mentions however, a "heart" (kokoro) that exist prior to the thought, at least in the hotelier. This Japanese heart has traditionally been refereed to as a mirror such as in the preface to the record of ancient matters (Kojiki).

Bibliography

Doi, T. (1973). The Anatomy of Dependence. Kodansha USA.

Krieger, S. (1983). The Mirror Dance: Identity in a Women’s Community. Philadelphia: Temple Univ Press.

うちのホテルにはおもてなしの心があるんで、人間じゃないとだめです。お客様のほしいこと、もしくは思っていることを先回りして考えてこうどうするんで、やっぱりおもてなしのこころは人間じゃないとだめだと

The "please help yourself" that Americans use so often had a rather unpleasant ring in my years before I became used to English conversation. The meaning, of course, is simply "please take what you want without hesitation," but literally translated it has some a flavour of "nobody else will help you," and I could not see how it came to be an expression of good will. The Japanese sensibility would demand that, in entertaining, a hose should should sensitivity in detecting what was required and should himself "help" his guests. To leave a guest unfamiliar with the house to "help himself" would seem excessively lacking in consideration. This increased still further my feelings that Americans were a people who did not show the same consideration and sensitivity towards others as the Japanese. As a result, my early days in American, which would have been lonely at any rate, so far from home, were made lonelier still. (Doi, 1973, p.13)

A Japanese capsule hotel manager, Akikazu Fukumoto, explains the essence of Japanese style hospitality (omotenashi) and why it would be impossible to replace his staff with robots in two sentences,

at the three minute mark in a video on robot staffed hotels in Japan by Motherboard.

My translation (for the original Japanese see below)

"Our hotel has the heart of Japanese hospitality (omotenashi no kokoro) and must therefore be staffed by humans. Our staff must be human because we behave proactively anticipating the thoughts and needs of the customer. "

The Motherboard translation is slightly off the mark since the hotelier does not "respond" to the needs and thoughts of the customer but pre-empt -- saki mawari, literally go around in front of -- them. If it were merely a case of "responding" to the needs and thoughts of their guests, the hotel could wait for the guests to express them verbally, and use robots, or untrained staff working to a manual, as is the case in Western style, customer makes overt choices, "help yourself" (Doi, 1973, p.13) hospitality.

Japanese hospitality is, when it works, a sort of "mirror dance" (Krieger, 1983) where the providers read the minds of their customers via their faces and behaviour, adjusting their own behaviour on the fly accordingly.

Contra what I have written elsewhere however, this hotelier seems to be implying that the thoughts of the customer are not expressed by their behaviour but come afterwards, perhaps in linguistic form. At its most effective, Japanese hospitality should preempt, and even prevent, the arrival of such thoughts by satisfying the need before the thought arises. The manager also mentions however, a "heart" (kokoro) that exist prior to the thought, at least in the hotelier. This Japanese heart has traditionally been refereed to as a mirror such as in the preface to the record of ancient matters (Kojiki).

Bibliography

Doi, T. (1973). The Anatomy of Dependence. Kodansha USA.

Krieger, S. (1983). The Mirror Dance: Identity in a Women’s Community. Philadelphia: Temple Univ Press.

うちのホテルにはおもてなしの心があるんで、人間じゃないとだめです。お客様のほしいこと、もしくは思っていることを先回りして考えてこうどうするんで、やっぱりおもてなしのこころは人間じゃないとだめだと

The "please help yourself" that Americans use so often had a rather unpleasant ring in my years before I became used to English conversation. The meaning, of course, is simply "please take what you want without hesitation," but literally translated it has some a flavour of "nobody else will help you," and I could not see how it came to be an expression of good will. The Japanese sensibility would demand that, in entertaining, a hose should should sensitivity in detecting what was required and should himself "help" his guests. To leave a guest unfamiliar with the house to "help himself" would seem excessively lacking in consideration. This increased still further my feelings that Americans were a people who did not show the same consideration and sensitivity towards others as the Japanese. As a result, my early days in American, which would have been lonely at any rate, so far from home, were made lonelier still. (Doi, 1973, p.13)

Labels: blogger, hospitality, japanese culture, japaneseculture, nihonbunka, 日本文化

This blog represents the opinions of the author, Timothy Takemoto, and not the opinions of his employer.