Sunday, October 09, 2016

Misunderstood Japan

Someone asked on Quora what do foreigners misunderstand about Japan. I answered as I always do that Foreingers at least since Ruth Benedict (1946) think that Japanese shame is external, imposed on them from the outside, when in fact the Japanese live in the sight of the Sun God, Amaterasu, or Otendou-sama (Funahashi, 2008) who watches from within their hearts.

This explains why for instance, the Japanese do tidy up not only football stadia (even when their national team loses) but also tidy up in the privacy of their hotel rooms (Funahashi, 2008, p.166) and toilet cubicles which they leave as if unused, contra non-Japanese guests.

Conversely it is because Japanese care about how things look from a special perspective in their hearts, NOT from the point of view of other people, which is the reason why Japanese cities are a bristling, bubbling morass of individuality as opposed to rows of houses all looking the same.

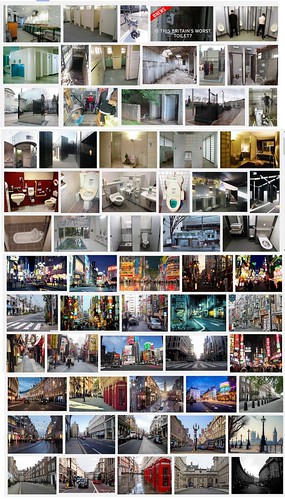

The above images are the Google image search results, at half size, for:

I Top) British public toilet inside

2) Japan public toilet inside

3) Tokyo Street

4) London Street

お取り下げご希望でありましたら、下記のコメント欄かnihonbunka.comのメールリンクからご一筆ください。Should anyone want me to cease and desist please send me a note via the comments or to the mail link at nihonbunka.com

Labels: collectivism, individualism, japanese, japanese culture, nihonbunka, 個人主義, 日本文化, 集団主義

Comments:

1) is it that the Japanese say they are not the same people as in the past by virtue of an act of apology that allows for a forgetting?

Yes, apology means that they do not have to keep imagining the past. But as I say, I am not sure what "different" means.

Doing a reverse Naclanian transformation, consider Locke's thought experiment regarding "the veil of perception;" the ellipse of qualia of colour. Locke is persuasive but at the same time, he does not go far enough. To a Westerner all visual phenomena are are subjective so they can't really be different from each other, or compared.

i) how about in intra-Japanese grievances? Does it imply a Japanese apology tends to be accepted and the matter forgotten?

If they look sincere. I find Japanese to be very forgiving. But there is a saying that the Buddha's face is only up to three times which means that you can say sorry for something three times but the fourth time you will be faced with a face that is still angry.

ii)And given the massive ongoing grievances with other Asian cultures, does it presume or imply that these other Asian cultures are more "narrative"?

That would be the implication.

> iii)more generally, how does this narrative of Japanese identity deal with the past, or more precisely, history, when the past is disconnectable with forgetting? "that was a good time for us" -- allows a person to point at an object more than 1000 years old and say "us"?

The I think that the "narrative of Japanese identity" is a movie, or manga. If there is a vase there in front of their eyes then the past is present and "us". The history as story is just words.

I think that Japanese need see themselves from the point of view of the victim before being allowed to forget the past, and continue to see themselves with those eyes. It is in the nature of linguistic evaluation (due to the arbitrary nature of signs, there "negativite'") that words only have meaning in comparison to other words, so testing will involve a comparison. But I think that our visual evaluation does not need to compare. That is just ugly! The proof that they have gone straight is in the fact that they do not do the same thing again, rather than in that they do not carry the past around with them.

Post a Comment

<< Home

You say "the Japanese live in the sight of the Sun God, Amaterasu, or Otendou-sama (Funahashi, 2008) who watches from within their hearts." Does this --- as opposed to "Western" guilt, presumably, and also external shaming --- manifest different characteristics at the moments of failure, neglect or even outright crime? That is, is the feeling of guilt, culpability, etc different at the moment of transgression? Are the strategies of dealing with it different from a western person's? --- Apologies if I am butchering the categories but I'm not familiar with the Lacanian school. (I assume nacalian is a play on Lacanian).

You say "the Japanese live in the sight of the Sun God, Amaterasu, or Otendou-sama (Funahashi, 2008) who watches from within their hearts." Does this --- as opposed to "Western" guilt, presumably, and also external shaming --- manifest different characteristics at the moments of failure, neglect or even outright crime? That is, is the feeling of guilt, culpability, etc different at the moment of transgression? Are the strategies of dealing with it different from a western person's? --- Apologies if I am butchering the categories but I'm not familiar with the Lacanian school. (I assume nacalian is a play on Lacanian).

Thank you Mazen

(I so rarely get comments!)

The Nacalian thing is Lacan backwards. He argues (along with a lot of other more intelligible theorists that I now wish I had used) that children first recognise themselves in mirrors as an image, but it is only language that provides a mental mirror, that enables children to see themselves as another in their minds. That is to say the Western view of the self and self-evaluation is "logo-phonocentric" a whispering in mind.

Likewise Mead's generalised other, Freud's super ego closely related to his unexplained "acoustic cap," Derrida's ear of the other and postcard recipient, the super-addressee of Bakhtin, and a myriad narrative self theories all say that humans are "homo narans" or "homo negatiatus" (a negotiating animal) or story telling animal.

The Nacalian thing is just to say that no, one can have a (normal visual) mirror in mind too. That is now argued by people like Metzinger, Olaf Blanke and the work on mirror neurons, and demonstrated by my only good paper ("Mirrors in the Heart" with Heine et a.). But it is less that we have a mirror so much as the self is always a representation or extrojection, and we know can identify with visual as well as linguistic self-representations.

Westerners are more invested in their narratives and theories, Japanese in their visual self representations: acts, corporeal creations.

Generally in the West shame comes from the gaze of otherS, but I think that Japanese people gaze from their minds too. And conversely generally in Japan, the ears or interlocutors are of real otherS but Westerners have a listener in their mind too. It seems to me more and more that really we *are* the terrifying listener and/or watcher, but we play different self-representation games.

This does make for differences regarding the social emotions and your questions are spot on.

> manifest different characteristics at the moments of failure, neglect or even outright crime?

Linguistic self-evaluation or guilt inevitably bears upon past transgressions at the moment of narration, rather than the act, whereas visual shame often occurs at the moment of act of transgression which is at the same time the representation of self.

Linguistic self-evaluation does however come to bear upon lies at the moment of speech acts, whereas shame culture(s?) are lenient towards speech-act-crimes which only become criminal when they are imagined or manifest in negative visual outcomes.

Visual self evaluation bears upon all negative images including mistakes, whereas linguistic evaluation only the narration or "will" so generally only on deliberate acts.

> Are the strategies of dealing with it different from a western person's?

Yes, great question. Strategies are very different. It is often said that guilt applies to the act whereas shame to the person but I think that this is more about the way in which one can re-narrate, rationalise, justify ones acts ("I was tired") so that the current "I" is extricated from the act, whereas in the act as replayed as a video ("video ergo sum" is Blanke's nice phrase) the self can not be extricated from the act. This means that shame must (after self improvement to help ensure that the act does not happen again which occurs in guilt too) be forgotten (or "flushed away in the water" as the say in Japan) whereas guilt need not be and indeed should not be forgotten. This leads to massive inter-cultural problems regarding attitudes towards past crimes such as war guilt. Let's move on already, say the Japanese. No! Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it! Says George.

(I so rarely get comments!)

The Nacalian thing is Lacan backwards. He argues (along with a lot of other more intelligible theorists that I now wish I had used) that children first recognise themselves in mirrors as an image, but it is only language that provides a mental mirror, that enables children to see themselves as another in their minds. That is to say the Western view of the self and self-evaluation is "logo-phonocentric" a whispering in mind.

Likewise Mead's generalised other, Freud's super ego closely related to his unexplained "acoustic cap," Derrida's ear of the other and postcard recipient, the super-addressee of Bakhtin, and a myriad narrative self theories all say that humans are "homo narans" or "homo negatiatus" (a negotiating animal) or story telling animal.

The Nacalian thing is just to say that no, one can have a (normal visual) mirror in mind too. That is now argued by people like Metzinger, Olaf Blanke and the work on mirror neurons, and demonstrated by my only good paper ("Mirrors in the Heart" with Heine et a.). But it is less that we have a mirror so much as the self is always a representation or extrojection, and we know can identify with visual as well as linguistic self-representations.

Westerners are more invested in their narratives and theories, Japanese in their visual self representations: acts, corporeal creations.

Generally in the West shame comes from the gaze of otherS, but I think that Japanese people gaze from their minds too. And conversely generally in Japan, the ears or interlocutors are of real otherS but Westerners have a listener in their mind too. It seems to me more and more that really we *are* the terrifying listener and/or watcher, but we play different self-representation games.

This does make for differences regarding the social emotions and your questions are spot on.

> manifest different characteristics at the moments of failure, neglect or even outright crime?

Linguistic self-evaluation or guilt inevitably bears upon past transgressions at the moment of narration, rather than the act, whereas visual shame often occurs at the moment of act of transgression which is at the same time the representation of self.

Linguistic self-evaluation does however come to bear upon lies at the moment of speech acts, whereas shame culture(s?) are lenient towards speech-act-crimes which only become criminal when they are imagined or manifest in negative visual outcomes.

Visual self evaluation bears upon all negative images including mistakes, whereas linguistic evaluation only the narration or "will" so generally only on deliberate acts.

> Are the strategies of dealing with it different from a western person's?

Yes, great question. Strategies are very different. It is often said that guilt applies to the act whereas shame to the person but I think that this is more about the way in which one can re-narrate, rationalise, justify ones acts ("I was tired") so that the current "I" is extricated from the act, whereas in the act as replayed as a video ("video ergo sum" is Blanke's nice phrase) the self can not be extricated from the act. This means that shame must (after self improvement to help ensure that the act does not happen again which occurs in guilt too) be forgotten (or "flushed away in the water" as the say in Japan) whereas guilt need not be and indeed should not be forgotten. This leads to massive inter-cultural problems regarding attitudes towards past crimes such as war guilt. Let's move on already, say the Japanese. No! Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it! Says George.

Thanks very much for a detailed response.

Starting with your last point, video ergo sum => self cannot extricate from act => therefore it must be forgotten otherwise cognitively it is too "un-degradable" while guilty I => creates separation between I and the act => guilt can and should remain. The former is really the past, the latter has some notion of fixed I, because, paradoxically, it can be distanced from its actions. Is this correct? So, Japanese say the warcrimes were the shameful past and we are no longer the same Japanese, Germans say we are guilty and the act somehow was an 12 year aberration from our true self?

Nacalian - I think I understand, although I think I slip between concepts of the visual and the gaze.

And how might this relate to the following experience: a few years ago we took my daughters to the 7-5-3 ritual. The whole atmosphere was about ritual without any further need to belong or be sincere or somehow believe. There was no need to be genuinely part of the religious community. We paid at the counter, (non-Japanese) names were written elaborately, given to the priest, and the collective purification / protection ceremony occurred and the names were read out anciently and that's it. My aunts felt that an important act was achieved. How different this is from monotheistic and not just monotheistic religions, where there is a need to in fact believe and demonstrate it, although even there there are gradients perhaps.

Starting with your last point, video ergo sum => self cannot extricate from act => therefore it must be forgotten otherwise cognitively it is too "un-degradable" while guilty I => creates separation between I and the act => guilt can and should remain. The former is really the past, the latter has some notion of fixed I, because, paradoxically, it can be distanced from its actions. Is this correct? So, Japanese say the warcrimes were the shameful past and we are no longer the same Japanese, Germans say we are guilty and the act somehow was an 12 year aberration from our true self?

Nacalian - I think I understand, although I think I slip between concepts of the visual and the gaze.

And how might this relate to the following experience: a few years ago we took my daughters to the 7-5-3 ritual. The whole atmosphere was about ritual without any further need to belong or be sincere or somehow believe. There was no need to be genuinely part of the religious community. We paid at the counter, (non-Japanese) names were written elaborately, given to the priest, and the collective purification / protection ceremony occurred and the names were read out anciently and that's it. My aunts felt that an important act was achieved. How different this is from monotheistic and not just monotheistic religions, where there is a need to in fact believe and demonstrate it, although even there there are gradients perhaps.

Further comments on 2nd comments:

Continuing on the theme of apology:

1) is it that the Japanese say they are not the same people as in the past (my short hand for water under the bridge) by virtue of an act of apology that allows for a forgetting? Is the issue precisely that they expect a reciprocal forgetting? A non-Japanese victim is infuriated by the notion that they also should forget, now that the apology has been delivered?

Several questions related to this visual-act relationship (as opposed to narrative-recollection):

i)how does this mechanism manifest itself in intra-Japanese grievances? Does it imply a Japanese apology to another Japanese tends to be accepted and the matter forgotten? Shikataganai?

ii)And given the massive ongoing grievances with other Asian countries/ cultures, does it presume or imply that these other Asian cultures are more "narrative"?

iii)more generally, how does this narrative of Japanese identity deal with the past, or more precisely, history, when the past is disconnected or disconnectable with forgetting? I recall a Chinese guide in Beijing pointing to a 9th century vase and saying: "that was a good time for us" -- to me the remark was amazing: what kind of relationship to the past / history allows a person to point at an object more than 1000 years old and say "us"? Is that possible in Japan?

2) if the German attitude is that they were guilty but that it was an aberration from the true self they want to be presently, then to admit guilt and apologise for it is about identifying how the crime was "out of character." A "setting of the record straight" occurs. All this by way of essentially regurgitating the victim's narrative, and then incorporating it into your own. So, is it, an act of bringing the victim's viewpoint and making it your own, somehow, and thereby saying the absence of that viewpoint was an elision in my (German) identity? (The question of sincerity vs. performance complicates this? The unspoken real feelings, etc...?) There is a learning implied, and it is continuously tested? Reaffirming the guilt means reaffirming it was learnt, and inherent in this is that it is testable because it is not forgotten.

Continuing on the theme of apology:

1) is it that the Japanese say they are not the same people as in the past (my short hand for water under the bridge) by virtue of an act of apology that allows for a forgetting? Is the issue precisely that they expect a reciprocal forgetting? A non-Japanese victim is infuriated by the notion that they also should forget, now that the apology has been delivered?

Several questions related to this visual-act relationship (as opposed to narrative-recollection):

i)how does this mechanism manifest itself in intra-Japanese grievances? Does it imply a Japanese apology to another Japanese tends to be accepted and the matter forgotten? Shikataganai?

ii)And given the massive ongoing grievances with other Asian countries/ cultures, does it presume or imply that these other Asian cultures are more "narrative"?

iii)more generally, how does this narrative of Japanese identity deal with the past, or more precisely, history, when the past is disconnected or disconnectable with forgetting? I recall a Chinese guide in Beijing pointing to a 9th century vase and saying: "that was a good time for us" -- to me the remark was amazing: what kind of relationship to the past / history allows a person to point at an object more than 1000 years old and say "us"? Is that possible in Japan?

2) if the German attitude is that they were guilty but that it was an aberration from the true self they want to be presently, then to admit guilt and apologise for it is about identifying how the crime was "out of character." A "setting of the record straight" occurs. All this by way of essentially regurgitating the victim's narrative, and then incorporating it into your own. So, is it, an act of bringing the victim's viewpoint and making it your own, somehow, and thereby saying the absence of that viewpoint was an elision in my (German) identity? (The question of sincerity vs. performance complicates this? The unspoken real feelings, etc...?) There is a learning implied, and it is continuously tested? Reaffirming the guilt means reaffirming it was learnt, and inherent in this is that it is testable because it is not forgotten.

Thank you.

With regard to 3-5-7, as you say it is not important to avow a belief but perhaps there is a way of seeing and imagining that corresponds to affirming statements - believing what you see is real which relates to your first point.

> Starting with your last point, video ergo sum => self cannot extricate from act => therefore it must be forgotten otherwise cognitively it is too "undegradable" while guilty I => creates separation between I and the act => guilt can and should remain. The former is really the past, the latter has some notion of fixed I, because, paradoxically, it can be distanced from its actions. Is this correct?

I am not sure. It seems to me that attitudes to time and space are reversed such that for Westerners space or "res-extensa" is subjective but time (the medium of the narrative) exists objectively the present, past and future too, whereas the Japanese feel that time is subjective whereas res extensa, the visual field exists objectively (Ernst Mach). Japanese enjoy the flow of time (sakura mujou) and try and stop the res-extensa through the use of all sorts of miniaturisation and perspective destroying artworks. Westerners enjoy the flow of space, vistas and perspectives but try and and stop time using loads of old buildings and antiques.

> So, Japanese say the war crimes were the shameful past and we are no longer the same Japanese, Germans say we are guilty and the act somehow was an 12 year aberration from our true self?

I think that is right for me and the Germans. I think perhaps for the Japanese the past only exists if is brought to the present, to mind. But what of the ancestors, and all the traditions? I guess that they are felt to be here now, at Obon. They go someplace else. If it exists then since time itself is purely subjective, 'the past is another country.'

With regard to 3-5-7, as you say it is not important to avow a belief but perhaps there is a way of seeing and imagining that corresponds to affirming statements - believing what you see is real which relates to your first point.

> Starting with your last point, video ergo sum => self cannot extricate from act => therefore it must be forgotten otherwise cognitively it is too "undegradable" while guilty I => creates separation between I and the act => guilt can and should remain. The former is really the past, the latter has some notion of fixed I, because, paradoxically, it can be distanced from its actions. Is this correct?

I am not sure. It seems to me that attitudes to time and space are reversed such that for Westerners space or "res-extensa" is subjective but time (the medium of the narrative) exists objectively the present, past and future too, whereas the Japanese feel that time is subjective whereas res extensa, the visual field exists objectively (Ernst Mach). Japanese enjoy the flow of time (sakura mujou) and try and stop the res-extensa through the use of all sorts of miniaturisation and perspective destroying artworks. Westerners enjoy the flow of space, vistas and perspectives but try and and stop time using loads of old buildings and antiques.

> So, Japanese say the war crimes were the shameful past and we are no longer the same Japanese, Germans say we are guilty and the act somehow was an 12 year aberration from our true self?

I think that is right for me and the Germans. I think perhaps for the Japanese the past only exists if is brought to the present, to mind. But what of the ancestors, and all the traditions? I guess that they are felt to be here now, at Obon. They go someplace else. If it exists then since time itself is purely subjective, 'the past is another country.'

1) is it that the Japanese say they are not the same people as in the past by virtue of an act of apology that allows for a forgetting?

Yes, apology means that they do not have to keep imagining the past. But as I say, I am not sure what "different" means.

Doing a reverse Naclanian transformation, consider Locke's thought experiment regarding "the veil of perception;" the ellipse of qualia of colour. Locke is persuasive but at the same time, he does not go far enough. To a Westerner all visual phenomena are are subjective so they can't really be different from each other, or compared.

i) how about in intra-Japanese grievances? Does it imply a Japanese apology tends to be accepted and the matter forgotten?

If they look sincere. I find Japanese to be very forgiving. But there is a saying that the Buddha's face is only up to three times which means that you can say sorry for something three times but the fourth time you will be faced with a face that is still angry.

ii)And given the massive ongoing grievances with other Asian cultures, does it presume or imply that these other Asian cultures are more "narrative"?

That would be the implication.

> iii)more generally, how does this narrative of Japanese identity deal with the past, or more precisely, history, when the past is disconnectable with forgetting? "that was a good time for us" -- allows a person to point at an object more than 1000 years old and say "us"?

The I think that the "narrative of Japanese identity" is a movie, or manga. If there is a vase there in front of their eyes then the past is present and "us". The history as story is just words.

I think that Japanese need see themselves from the point of view of the victim before being allowed to forget the past, and continue to see themselves with those eyes. It is in the nature of linguistic evaluation (due to the arbitrary nature of signs, there "negativite'") that words only have meaning in comparison to other words, so testing will involve a comparison. But I think that our visual evaluation does not need to compare. That is just ugly! The proof that they have gone straight is in the fact that they do not do the same thing again, rather than in that they do not carry the past around with them.

<< Home

This blog represents the opinions of the author, Timothy Takemoto, and not the opinions of his employer.